February 14, 2013

No Comments

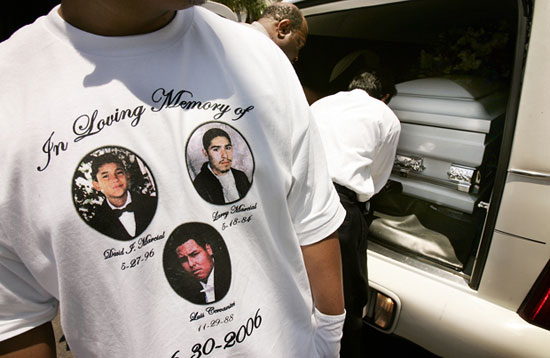

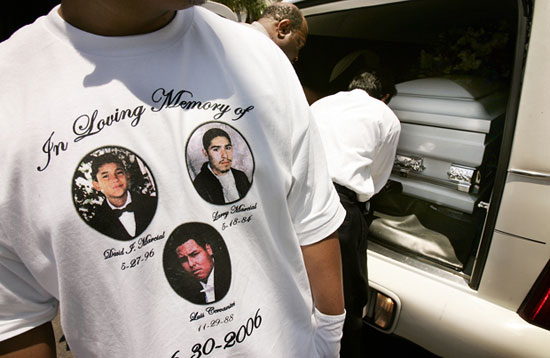

A county reward helped authorities find the Glendale driver in a fatal hit-and-run. Photo/Bryan Frank

Just hours before fugitive ex-cop Christopher Dorner was finally cornered in a hijacked cabin near Big Bear, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors had joined the manhunt: On Tuesday morning, it authorized a $100,000 reward for his capture, on top of the $1 million offered in private and public funds by the City of Los Angeles.

Now, with the quadruple murder suspect dead, it’s unclear exactly how—or if—the county’s bounty will be doled out to those who’ll inevitably step forward asserting that their information was crucial in Dorner’s discovery and demise. Ultimately, under county law, a recommendation will be made by representatives of the Chief Executive Office, Sheriff’s Department and Board of Supervisors, whose five members will have the final say.

The Dorner reward made news, of course, because of the international magnitude of the case, upstaging even President Obama’s State of the Union address as the drama came to a fiery conclusion Tuesday evening. But with less fanfare, the county for decades has been offering and paying rewards for information that has helped authorities obtain convictions for crimes ranging from multiple murders, to racially-inspired vandalism to animal cruelty.

During the past five years, the Board of Supervisors has authorized more than 140 reward offers—totaling $1.9 million—on behalf of law enforcement agencies throughout the county. Of those, the county has paid 25 claims worth about $225,000. The biggest payout came last April, when 10 people shared $30,000 for providing information that led to the arrest and conviction of assailants in the so-called “49th Street Massacre.” In that 2006 tragedy, three people, including a 10-year-old boy on a bike, were gunned down in a mistaken identity gang shooting in South Los Angeles.

Over the years, questions have been raised about how crimes are selected for rewards and whether the publicity surrounding a case—or the victim’s race—might unduly tip the scales. In the late 1990s, entertainer Bill Cosby asked that several taxpayer-funded reward offers be rescinded after his son, Ennis, was murdered while changing a tire on a darkened road near Bel Air. The family did not want to make it appear they were getting preferential treatment. Although the state and City of Los Angeles declined Cosby’s request, the Board of Supervisors withdrew its $12,500 reward.

For the most part, however, law enforcement officials dismiss such concerns and criticisms, saying they only seek rewards from the supervisors or other municipal bodies when investigations of particularly heinous crimes go cold and the public remains at risk.

“They are effective, absolutely,” Sheriff’s Department spokesman Steve Whitmore says, although he acknowledges that the offer of money can make investigations more complicated. “A lot of the tips aren’t fruitful,” he says. “But the important thing is that a lot of them are.”

Such was the case for frustrated Glendale Police Department detectives, whose investigation into the hit-and-run death of Elizabeth Sandoval in 2007 was at a standstill. The 24-year-old woman was thrown 100 feet after she was struck by a black Mercedes-Benz as she jaywalked across Glendale Avenue in the darkness of night.

“If the driver could just look into their heart and see that things would be better for him or her if they came forward,” Sandoval’s grief-stricken father pleaded after his daughter’s death. “Just do yourself a favor and turn yourself in,” her brother urged.

But it wasn’t until the Glendale City Council and the L.A. County Board of Supervisors each offered $10,000 in reward money that police got a breakthrough that led to the arrest and conviction of Ara Grigoryan, 23, who, according to the informant, had fled to Mexico.

Without the reward, says Glendale police spokesman Sgt. Tom Lorenz, “it would never have gotten solved.” The informant, he says, “made it very clear to us that she called because there was an offer of a reward…She kept calling back until she got the money.”

Slain deputy Maria Cecilia Rosa

Long Beach police officials, meanwhile, credit a $25,000 county reward with helping them crack one their biggest cases in recent years—the 2006 murder of Los Angeles County Deputy Sheriff Maria Cecilia Rosa. She was shot twice just after dawn by robbers while loading bags into her car before heading from Long Beach to her assignment in the county jails. “It was a coldblooded killing,” Sheriff Baca told the media. “Who is truly safe? No one.”

A little more than a month after the reward offer, an informant gave Long Beach police the name of the suspected gunman and arranged a meeting between detectives and another individual who revealed where one suspect was believed to be living. In the end, two men—both of whom were already serving state prison time—were convicted in the deputy’s murder. One was sentenced to death; the other was given 29 years to life.

“The reward prompted an otherwise unwilling witness to come forward and provide information which allowed detectives to focus on a small group of suspects,” says Long Beach police spokesman Sgt. Aaron Eaton.

Long Beach police also benefitted from another reward offered by the county—this one involving the murder of popular honors student Melody Ross, 16, who was hit by gunfire that was sprayed into a group of young people leaving the 2009 Wilson High School homecoming football game. Two witnesses shared the $20,000 reward after giving authorities information that led to the arrest and conviction of two teenaged defendants.

Financial incentives, Easton says, “sometimes mean the difference between making an arrest or the case going unsolved.”

But not always.

The largest county reward anyone can remember—$150,000—was first offered in late 2002, after the death of 15-year-old Brenda Sierra, whose body was found off a mountainous road in San Bernardino County. She died from a blow to the head. The unusually high reward was approved by the board at the request of Supervisor Gloria Molina, whose district includes East Los Angeles, where the teenager lived and was last seen alive.

For nearly a decade, the reward was repeatedly renewed for six-month stretches in the hopes that someone would come forward and bring a measure of closure to the long grieving family. “Until we find her killer, we’re not giving up,” Molina said in announcing the award’s extension in July, 2009.

The reward finally expired in mid-2010, and the case remains unsolved.

Police got a break in the “49th Street Massacre” case thanks to a $30,000 reward. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 2/14/13