July 18, 2013

No Comments

Lisa Cianci and Ben Lawson of Ant Permie’s are among hundreds taking advantage of the Homemade Food Act.

Gene Holmon’s spice mix was so good that his Woodland Hills family urged him to sell it. Jessica Schnyder learned to make jam and pickles from her Hollywood chef friend, Amanda Carr.

Kyle and Liz von Hasseln, grads of Southern California Institute of Architecture, were playing with a three-dimensional printer one day when they realized they could make sugar sculptures. Shantal Derboghosian, a Van Nuys engineer, was unemployed when she discovered a gift for baking. Ben Lawson perfected his organic, sustainable trail mix in Topanga when he wasn’t drumming for a Long Beach punk/grind-crust band.

Until about six months ago, few, if any, of them could have profited much from their passions. But today, they and hundreds of others are part of an entrepreneurial boomlet ignited by a new state law allowing Californians to make food for sale from their home kitchens.

The California Homemade Food Act, which created a new category of food production called “cottage food operation,” has been in effect since January and, according to health officials, few places have seized on it with the excitement of Los Angeles County.

Spurred by L.A.’s creative culture and California’s artisanal food movement, a home-based underground of bread makers, cookie bakers, coffee roasters, marshmallow puffers, marmalade canners, baklava peddlers and just about every other imaginable kind of food purveyor has come out from behind the stove to pull permits.

“Our numbers are very high compared to other jurisdictions,” says Director of Environmental Health Angelo Bellomo, who notes that, so far, more than 500 applications have been filed with the county for permission to prepare and sell non-perishable food products at home rather than in expensive leased space in certified commercial kitchens.

Of those, he says, about 200 have been approved; most of the rest are awaiting payment of annual fees ranging from $103 to $254, depending on whether the business is direct sale only or includes sales through restaurants and markets. (Click here and here for the most recent list of permit holders.)

“There’s been a lot of interest on the part of those who have always dreamed of having a home enterprise.”

The development is no surprise to Mark Stambler, a Los Feliz artisan baker whose naturally leavened organic French bread sparked the state law in 2011 after it started flying off the shelves in local cheese shops and restaurants.

“I was selling a good number of loaves each week, and as long as I kept my head down, no one was the wiser,” says Stambler, whose bread was baked in his backyard in a wood-fired stone oven.

But over time, his bread became the talk of foodie L.A., and the Los Angeles Times ran a story, telling readers where they could find it. Within 24 hours, he says, county health inspectors descended on the shop where his goods were being sold and informed customers that it was illegal to sell food that hadn’t been prepared in a commercial kitchen.

Stambler responded with an 18-month crusade to open the system, with the help of his local state legislator, Assemblyman Mike Gatto (D-Silver Lake). The new law applies only to “non-potentially hazardous food” such as bread, preserves, dried foods and other goods whose ingredients don’t include meat, cream or other perishable items. It requires home food producers to complete a course in food processing and the labeling of their products. Those who want to sell their wares in bakeries, markets and restaurants also must undergo a kitchen inspection.

But even with the law’s limitations, the activist baker—who says he lost two-thirds of his business after the county crackdown—says he’s been thanked repeatedly for pushing the changes.

“I’ve heard from people all over the state, saying they really needed this for the added income,” he says.

A happy Shantal Derboghosian of Shakar Bakery with her new fridge in her Van Nuys apartment.

The cottage food option was certainly helpful for Shantal Derboghosian, who coped with a spell of joblessness by opening Shakar Bakery out of her one-bedroom apartment in Van Nuys. Specializing in custom cakes (her business name is Armenian for “sugar”), the 31-year-old environmental engineer found herself spending six to eight hours on her creations—a labor of love if it’s in your own kitchen, but a hefty bite out of your bottom line if you have to pay an hourly rate for a commercial workspace.

“I was renting kitchen space,” she says, “but they were charging about $25 an hour and it was expensive. My first official client was a three-tier baptism cake for 150 people, with a lot of sculpting—it was a nautical thing, with whales and waves and little anchors.”

Her current project is a 5-foot-tall, flashing tribute cake modeled on the French techno-music duo Daft Punk that she created with the help of Garen Khanoyan, a fellow engineer whose day job is at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “These things aren’t quick to do,” she notes.

Neither is building a business, Kyle and Liz von Hasseln say, noting that the new rules have bought them crucial time to scale their custom sugar sculpting business, The Sugar Lab.

The couple says their concept was born in 2010, when they were architecture students at the Southern California Institute of Architecture downtown and a friend announced it was her birthday. “Our thesis at SCI-Arc was on new developments and free-form fabrication, which is the catchall phrase for 3-D printing,” says Kyle von Hasseln. “We were living in a teeny little apartment in Echo Park and we didn’t have an oven. So we decided to try to 3-D print her a sugar cake topper for her birthday cake.”

The idea took months of trial-and-error, he says, but eventually it yielded an extraordinary manufactured sugar sculpture that has since led to a series of custom assignments for birthday parties and weddings in collaboration with a local bakery. Their latest project? A stunning 3-D sugar diamond, done on spec for GLAAD, celebrating the U.S. Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage decision.

“We could invest in commercial kitchen space, but it would be hard for young entrepreneurs just out of grad school with a lot of debt,” he says.

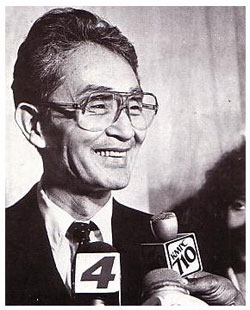

Gene “Cappy” Holmon and wife Paulette have found a new calling in retirement.

For many artisans, however, the cottage food permits are simply a chance, at last, to see whether their ideas have a market.

“We love food and want to have our own business,” says Schnyder, a 26-year-old Mar Vista restaurant manager who has teamed with her 29-year-old friend Carr to launch Calliope Canned Commodities, a sideline she says expresses their enthusiasm for jams, pickles and Victorian circus musical instruments.

“What we make requires such a slow process and such small batches that you don’t need a lot of space to do it, Schnyder says. “But until now, we haven’t been able to sell it. We’ve just given it away to our friends.”

For Lawson, the drummer, the cottage food program has been a way to market not only his Ant Permie’s trail mix but also his belief in sustainability, local trade and emergency preparedness.

“We all know of local cafes that serve, you know, brownies that some old lady made in an apartment that are so good that nobody drops a dime on them,” he says. “Now that kind of thing can be legal.”

His signature organic snack is made at Cross Bull Ranch, the permaculture collective and retreat where he lives in Topanga, and is sold in airtight, rodent-proof, 5-gallon buckets that, depending on storage conditions, can keep food fresh “for months to years.”

As for Gene “Cappy” Holmon and his wife Paulette, the law has provided an answer both to those who have clamored over the years for his secret Cappy’s Dry Rub spice mix and to the retired couple’s own prayers.

“We had played with the idea for years,” says Paulette, a former costume designer. “Then this law passed, and the Heavenly Father just told us one day, ‘You guys should do something with it’.”

“Everybody seems to like it,” marvels Gene, a 66-year-old disabled veteran and retired small business owner. “Hey, we don’t play golf, so we’ve got to do something, right?”

Kyle and Liz von Hasseln of The Sugar Lab are making sugar sculptures from a 3-D printer.

Posted 7/18/13