Love and hate in the express lane

When it was time for the public to finally be heard on Los Angeles’ new freeway toll lanes, Metro got an earful.

“I love the Metro Express Lanes!!!!! We should have them throughout the city.”

“These fast track lanes have turned into nothing but Lexus Lanes.”

“Express Lanes are the best thing ever to happen to Los Angeles freeways.”

“The Express Lane program is an absolute joke.”

“Please Please Please…expand the express lanes!!!!!!

“ADMIT IT—IT’S A FAILURE!!!!

Metro had asked for the public’s take in March as part of a broad analysis to help the agency’s board of directors determine whether the “high occupancy toll lanes” on two of Los Angeles’ busiest freeways—the 110 and 10—should be made permanent. And on Thursday, the directors gave a unanimous thumbs-up to extending the experiment, despite the deeply divided motoring public reflected in the more than 700 emails the agency received.

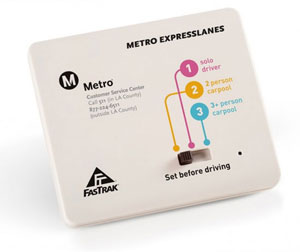

The federally-funded program lets solo drivers, who pay a toll, share lanes with carpoolers, who can continue to drive in them for free, with one important and controversial caveat: everyone must have an electronic device called a transponder to use the “ExpressLanes.” That requires putting $40 into a “pre-paid” toll account, unless a person’s income qualifies him or her for assistance.

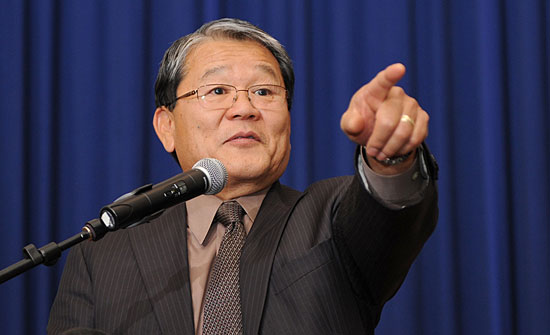

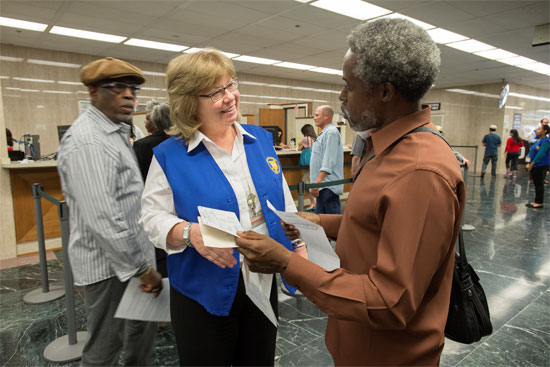

Stephanie Wiggins, Metro’s executive in charge of the toll lanes, presented the analysis to the board on Thursday. She said in an interview that she’s “never, never, never” had a job that has attracted so much public heat. “People really love them,” Wiggins said of the new lanes, “or they really hate them. There’s no in-between.” By overwhelming majorities, according to a Metro survey, those who obtained transponders are happy and those who didn’t are not.

Metro director Mike Bonin, who also is a member of the Los Angeles City Council, lauded the pilot program but acknowledged, like others on the board, that it is still a work in progress. “We’re in the breaking eggshells phase of making an omelet,” he said.

It’s not surprising, of course, that the dramatic changes would generate consternation and confusion among motorists who for decades have been freely using the carpool lanes—for 39 years on the 10, east of downtown Los Angeles, and 15 years on the 110, which slices through the heart of the city.

Statistical measures compiled by federal transportation officials in advance of the board’s vote have done little to settle the debate. They can be used by either side to make a glass-half-full/half-empty argument.

The pilot program was intended to improve traffic flow in both the toll and “general purpose,” or free, lanes, while also encouraging the use of transit alternatives, such as the Silver Line buses that travel along the toll lanes. So far, bus ridership has jumped but traffic times are not much different than before the experiment, according to a recent analysis by an independent firm hired by the Federal Highway Administration. Some drive times are slightly faster since the tolls went into effect, while others are slower, depending on the specific hours studied during peak morning and afternoon traffic.

Wiggins acknowledged that “the numbers, on their face, look marginal.” But she said there’s a clear bright spot, too: Solo drivers who’ve moved from the free lanes into the toll lanes have saved more than 17 minutes on some of their drives. And for those who haven’t changed their behaviors and remain in the free lane, they’re not really any worse off than they were before, she said. “And that can be perceived as a positive.”

What’s more, Wiggins noted that the $18 million in net toll revenues generated since the pilot began has far exceeded early projections. That means more money can be reinvested in transit improvements and inducements along the freeway corridors and that no public subsidies will be necessary in the future because the project is raising enough money to be self-sustaining.

As of February, some 260,000 transponders have been issued by Metro, well above the 100,000 that had been set as an initial goal—a fact that prompted board member and L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to remark: “People are voting with their cars.”

Wiggins also reported to the board that, in the future, Metro will work even more closely with the California Highway Patrol to crack down on scofflaws who drive in the lanes without transponders and to ticket solo drivers who cheat the system by setting their transponders to get a free ride by claiming multiple people are in the vehicle.

One of the most controversial elements of the toll lanes project had been the initial imposition of a $3 monthly “maintenance fee” on people who purchased transponders but who used the toll lanes fewer than 4 times a month. The fee was intended to recoup a charge levied for each transponder on Metro by the toll lane’s private operator.

To legions of travelers, it seemed unfair that anyone should be charged for not using something. To encourage drivers to participate in the toll lanes experiment, the Metro board last year waived the fee for Los Angeles County residents, who represent 86% of account holders, according to Wiggins.

On Thursday, the Metro board attacked the issue again, this time voting 8-3 in favor of a motion by director and L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina to impose a $1 monthly fee on everyone with a transponder, no matter how often they use the toll lanes. In this way, she argued, Metro will no longer be underwriting the fee and will have some $2 million more annually to reinvest in the system and in transportation benefits in communities along the 10 and 110 freeways.

Now that the toll lanes are becoming a permanent part of Los Angeles’ famous (infamous?) car-centric landscape, Wiggins said it’s crucial that Metro do a better job of communicating the value of the program to motorists.

A top priority, she said, will be to educate the public on how transportation is funded.

“We didn’t do ourselves any favors,” she said, “by naming them freeways because we know freeways aren’t free.”

Posted 4/24/14