The Insider

Meet our new “coroner to the stars”

July 9, 2013

Highly skilled with a scalpel, L.A.'s new coroner will now have to become facile with the celebrity-struck media.

Dr. Mark Fajardo has done thousands of autopsies in the dozen or so years he has spent as a forensic pathologist with Riverside County. From Palm Springs retirees to meth addicts to the renegade former Los Angeles Police Officer Christopher Dorner, he has examined all walks of toe-tagged life.

Still, as the Board of Supervisors named him Los Angeles County’s new chief medical examiner-coroner on Tuesday, Fajardo acknowledged that L.A. has one kind of death to which he’ll have to become accustomed when he steps into the job in August.

“In Riverside County,” he says, laughing, “we run the gamut—except for the celebrities.”

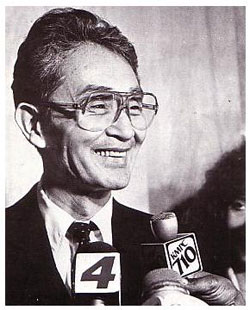

Fajardo, 49, succeeds Dr. Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran, who will retire this year after more than 21 years in the position that has come to be viewed as perhaps the nation’s most public coroner’s job.

Marilyn Monroe’s death was investigated by the Los Angeles County Department of Coroner; so were Sen. Robert F. Kennedy’s and Sharon Tate’s and Janis Joplin’s and John Belushi’s and Notorious B.I.G.’s and Michael Jackson’s and Whitney Houston’s and the paparazzo who died earlier this year trying to get a photo of Justin Bieber.

So many high profile cases come through the department, in fact, that in some instances, they’ve boosted the coroner himself to star status. Between 1967 and 1982, Dr. Thomas T. Noguchi came to be known as the “coroner to the stars.”

“I haven’t had to interact with the press much at all, so this will be interesting,” says Fajardo, noting that he hopes to follow Sathyavagiswaran’s lead and delegate most of the media interaction to someone else in the department. Despite a nationally televised stint on the stand during the trial of O.J. Simpson, the current coroner came to be known less for his time in the spotlight than for his competence in rebuilding the department after Noguchi and his successor, Ronald Kornblum, left their jobs amid management lapses and critical audits.

Nonetheless, Fajardo says, when he visited the department, he and Sathyavagiswaran talked at length about the challenges of dealing with death, L.A.-style.

“He told me that you lose all privacy, that you might have any member of the press asking any question at any time, and that you have to be prepared to answer openly,” says Fajardo. “And we talked about the media’s involvement in the case of Michael Jackson. He said there was such a caravan of cameras and paparazzi that they had to utilize a helicopter just to get him from Point A to Point B.”

That said, Fajardo says he’s looking forward to the $275,000-a-year job, which brings him and his wife, a San Bernardino County employee, back to his hometown.

Born at LAC+USC Medical Center, he spent his childhood in East Los Angeles and Pico Rivera. When he was 12, his father, a Los Angeles County deputy sheriff, was killed in an automobile accident on the way to work, and the family moved to be near relatives in Santa Maria.

It was there, while Fajardo was in high school, that the door to his current career opened.

“I took a class at a local community college to learn how to be an EMT,” he recalls.

That skill helped pay his way through his undergraduate training and medical school at UC Davis, where he initially aspired to be an emergency room doctor.

“I actually ran the student clinic at UC Davis,” he remembers. “But the people I played basketball with were pathologists and the friendships I made led me down that path instead.”

At Riverside County, he says, he has performed more than 5,500 autopsies, including more than 350 homicide cases while managing seven full- and part-time pathologists and helping manage a department that handles some 11,000 cases a year.

“This is as far removed as you can get from what most people think of as working as a doctor,” says Fajardo. “But for me, every case is a puzzle I get to solve, hopefully in a way that gives their families closure. I speak for the dead. I try to answer the questions about how they lost their lives.”

Demographically, he says, his caseload isn’t much different than Los Angeles County’s.

“We have our share of homicides,” he says ruefully. “And we’ve had six officer-involved shootings in the last month.”

But while the Riverside County coroner’s operation is large by some measures, serving about 1.3 million people, its constituency is only a fraction of the size of L.A. County’s.

“To me, that’s probably the biggest challenge,” says Fajardo. “Ten million people and all of them have needs. And we have to meet them—we provide a service, just like sheriff’s deputies and firefighters. It’s just that, unless a celebrity dies, people just don’t notice us as much.”

Posted 7/9/13

Score two for mental health

May 14, 2013

Mutual fans: Stella March, center, with Laker star Metta World Peace. At left, county mental health director Marvin Southard and chief deputy Robin Kay. Photo/Los Angeles County

“How’s Kobe doing?”

The question came from 97-year-old Stella March, a stalwart Lakers fan for decades. And it was directed at someone she thought would know—Kobe Bryant’s teammate, Metta World Peace.

“He tried to fight through it, but he couldn’t,” Metta said of Bryant and the Achilles tendon he tore on the eve of this year’s NBA playoffs. “He’s doing better now,” he assured March.

“I felt badly for him,” she said softly.

Then March turned the conversation toward Metta—and her observations had nothing to do with hoops. “What you’re doing for the kids, it’s very meaningful,” she told him. As they talked, they held hands.

From outward appearances, these two—the tiny white-haired woman with the walker and the towering player with the muscular arms—might seem like an odd pairing for a meeting of the Board of Supervisors. But as both would be quick to tell you, you can’t judge what’s inside from the outside. For they share a mission that transcends their cultural and generational divide; both are committed to destigmatizing mental health problems and treatment. And in that respect, both are very much on their game.

March and MWP, as the former Ron Artest likes to be called, were honored Tuesday by the board to kick-off “Mental Health Awareness Month.”

March is widely recognized as one of the nation’s preeminent advocates for families whose lives have been touched by mental illness, a crusade she began in the late 1970s after her son, a UCLA student, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Among other things, her efforts led to greater government and pharmaceutical research, ultimately helping to produce a new generation of medications. She also was the driving force behind building the National Alliance on Mental Illness and initiating its “StigmaBusters” program to combat inaccurate representations of mental illness in film, television, print and other media.

In those early years, she says, mental health treatment and research was so bad that many serious sufferers “were wandering around on the streets with nowhere to go. They were shunned and stigmatized as dirty street people.” With her organization’s help and support, she says, many of the severely afflicted “learned the basic skill of telling people how they recovered. Each one had a different story of recovery. It was fantastic.”

Metta World Peace understands the power of that message. Ever since he made headlines by thanking his therapist on network television after the Laker’s 7th-game championship victory in 2010, the once-troubled player has openly talked about his counseling for anger and family issues. In December of that year, he teamed up with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health to produce a public service announcement aimed at encouraging young people to seek help. “Talk to somebody about it,” he says in the PSA. “I did. Take the first steps. Be a champion.”

Since then, he’s also made his pitch during high school assemblies here and across the country and has created a website called Limelight that promotes mental health treatment. A new public service announcement campaign between Metta World Peace and the county—called “Talk it Out”—was launched earlier this month and will continue throughout May.

Before their Tuesday appearance before the Board of Supervisors, March, a fan of MWP’s moves on and off the court, asked to meet him in a small conference room behind the board’s dais, where he was signing posters for the new campaign. Helped into the room by her daughter, Joella, and officials from the mental health department, March was greeted by the 6-foot-7 player with an embrace, as though she were the star. He then took a seat beside her so she wouldn’t have to strain looking up at him.

“Thank you for what you’ve done to help,” she told him. “We’ve got to keep advocating for people.”

She needn’t worry. As Metta World Peace told the audience in the board’s hearing room: “This is a lifetime work.”

Posted 5/14/13

Taking a bite out of animal cruelty

April 11, 2013

Abusers beware: Eva Montes and her crack team in the county animal control department are on the case.

What began 15 years ago simply as a promising job for a struggling single mom of three youngsters, has become a calling. “I am a voice for the animals,” says Eva Montes.

Those animals have come in all sizes and shapes, from furry to feathered, but they’ve suffered a common fate: they’ve been treated badly by people—sometimes through ignorance, sometimes with malice. And it’s not just about the animals.

“Most serial killers started with abusing animals,” Montes says, “and we have to put a stop to that early.”

Montes belongs to a select squad inside Los Angeles County’s Department of Animal Care & Control that investigates the agency’s most complex cases of animal neglect and cruelty. Called the Major Case Unit, its seven members tackle everything from highly organized pit bull and cockfighting rings to cat hoarders to single cases of heartbreaking—and criminal—abuse.

On Tuesday, she was among more than a dozen uniformed colleagues picked to represent the department before the Board of Supervisors as part of “Animal Control Officers Appreciation Week in Los Angeles County.” While the agency is best known for its shelter system and efforts to find adoptive homes for animals, the largely unsung detective work of its Major Case Unit, or MCU, is central to the agency’s mandate.

“By our very mission, we’re charged with protecting the public and protecting animals,” says Deputy Director Aaron Reyes, who oversees the unit. “One of the best ways we can do that is to investigate crimes of cruelty, abuse, neglect and illegal animal fighting.”

Reyes says the MCU was created more than a decade ago when it became clear that the massive volume of calls handled by animal control officers was preventing them from undertaking sustained and difficult investigations. Until last year, the MCU had been based in the original “pound master’s house” at the department’s first-ever facility, which opened in Downey in 1946. But Reyes says he thought it was crucial to get the team’s members “onto the front lines” and base them in various shelters, where they could initiate investigations more quickly and share their expertise and insights with other officers.

The idea to scatter the team was not met with enthusiasm.

“We were against it,” recalls Montes, who’s been in the unit for nearly three years. “We hung out together. We were family. But it’s worked out better.” Since being assigned to the Carson Animal Care Center, Montes says, she’s found potential abuse cases “that were slipping through the cracks” because some officers were not creative enough in their investigations or sufficiently trained to spot signs of less obvious abuse or neglect when people were bringing dogs to the shelter.

Since last July, Montes says she has, for the first time, initiated a number of investigations of people who’ve brought dogs to the facility, including a woman who recently turned in a pit bull that looked like it had been used for fighting. A warrant for her arrest was recently issued. Last November, Montes was instrumental in a joint investigation with the SPCA Los Angeles that led to a long list of cruelty charges filed by the district attorney’s office against the owner of a Gardena guard dog business.

Being assigned fulltime to the Carson shelter, which serves some of southern Los Angeles County’s most impoverished neighborhoods, has been a culture shock for Montes. Before her promotion to the MCU, she spent nine years in the county’s Agoura Animal Care Center, high in the mountains above Malibu. She calls it “the Club Med of shelters.” The dogs, she says, are mostly of the “frou-frou” variety, and volunteerism is robust, something for which she’ll always be grateful on a very personal level. During Montes’ tenure there, her 14-year-old daughter died from a form of bone cancer. Volunteers built a misting system to keep the animals cooler during the summer months and dedicated it with a plaque in honor of Montes’ daughter, Jessica.

“She really respected my job,” Montes says of her girl. “If she could only see me now.”

In contrast to the Agoura shelter, Montes’ current assignment has exposed her to some of the meanest dogs and toughest owners in the department’s jurisdiction, a swath of southern Los Angeles County where “gang members represent themselves with their dogs.” Sometimes, she says, packs of “dominant breed” dogs such as Rottweilers and pit bulls roam the streets. “It’s scary,” she says. “I worry about getting bit and never being able to work again.”

Montes says she’s received cooperation during her neighborhood investigations but has been told by some male officers that they’ve encountered resistance when responding to complaints, being warned: “Get off my property or I’ll shoot you.”

One of Montes’ colleagues in the Major Case Unit is Armando Ferrufino, who, like her, also works in the southern part of the county. An expert on cockfighting, he’s assigned to the Downey Animal Care Center. And like Montes, he also feels as though he’s a voice for the animals.

He tells the story of a man who, for months, allowed his Rottweiler, Duke, to deteriorate into a mass of tumors and sores, refusing to seek medical help despite the animal’s obvious suffering. Acting on a tip, animal control officers rescued Duke, but he was too far gone to save.

“I felt like the spirit of the animal was telling me to do the right thing, to investigate and get the whole truth,” Ferrufino says. “And I did.” The owner was charged with a felony and sentenced to three months in county jail.

Ferrufino, who joined the MCU in 2009, says one of the most sensitive assignments involves animal hoarders, mostly lonely elderly people whose homes are filled with scores of cats, a good number of them ailing. “In their mind,” Ferrufino says, “they believe they are doing the right thing—showing them love—but it gets to the point where they can’t take care of them.”

If the neglect is severe, he says, then charges are pursued. Authorities also provide referrals for counseling. What’s more, the county has a program to help clean homes after animals have been removed during often tearful negotiations with owners. “It’s an illness,” Ferrufino says. “They’re not aware they’re doing something wrong.”

As difficult and wrenching as the work can be, Ferrufino says, he’s found his calling, too.

“Every day I come to work, I’m happy,” he says. “You don’t know what’s going to happen next, from hoarders to horses to cockfights.”

Montes agrees. “Some people like to stay in the shelter environment. But I saw other officers out there getting justice and I said: ‘That’s what I want to do.’ “

Posted 4/12/13

Front and center at Probation

April 4, 2013

Margarita Perez has brought experience and energy to her new high-profile job with Los Angeles County.

Unlike countless showbiz hopefuls waiting on tables or schlepping to auditions, it didn’t take long for Margarita Perez to land a Hollywood gig. Not that she even thought about breaking into the business when she hit town.

After all, her day job is now among the most important in Los Angeles government. Five months ago, after years in Sacramento, Perez was tapped to help remake the county’s Probation Department and guide its response to California’s controversial AB 109 law, which has placed thousands of former state prison inmates under the agency’s supervision.

On Thursday nights at 7, Perez can be seen hosting a news segment on KCOP-TV Channel 13 called “L.A.’s Most Wanted.” The unique collaboration between the station and the Probation Department calls on the public for tips to help track down five former convicts each week—most of them with serious raps sheets—who’ve disappeared into the community.

“I think it’s exciting,” Assistant Chief Probation Officer Perez says of the segments, which began airing last week. “It’s a great opportunity to highlight probation’s good work and engage the public in holding accountable those offenders who are not availing themselves of our oversight.”

And don’t be deceived by her looks. Although diminutive and fashionable, the high-octane Perez means business. She’s a self-described former “gun-toting parole agent” who broke into the criminal justice system as a guard at Avenal State Prison, a men’s institution in Central California. As an officer in the California National Guard, she was awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious achievement after entering Iraq with the front-line troops during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. “I’m as gung-ho as they come,” she says.

Perez says her parents, born and raised in Mexico, “drove into my head that your success revolves around you. There are no crutches. If you’re not successful, then you didn’t take advantage of the opportunities in this country.”

That advice propelled Perez through the California corrections bureaucracy during a career of more than two decades. Last year, she was put in charge of the Adult Parole Operations Division, where she was responsible for 3,500 employees and a budget of about $650 million.

But that job was increasingly looking like a dead end because of AB 109, the so-called “realignment” law enacted to ease overcrowding in the state’s 33 prisons and save money. As supervision of certain newly released inmates shifted to California’s counties, there was less work for state parole officers, who increasingly faced layoffs. Perez says the number of state-supervised offenders plummeted from 128,000 to 50,000, with only more of the same ahead.

So Perez was ready for a new challenge, a desire that made its way to Los Angeles County Probation Chief Jerry Powers, who assumed the top job in October, 2011, with a mandate to not only implement AB 109 but to also shake-up a department rife with personnel and financial problems. For months, he’d been unable to field a top management team with the expertise he believed necessary to tackle the enormous issues confronting the agency.

“To be honest, I was wearing down,” Powers says. “I was trying to cover the entire house with just me.”

But late last year he found his reinforcements in Perez, whom he hired to oversee adult and juvenile field operations, and in Sacramento County’s former probation chief, Don Meyer, whom he put in charge of the department’s juvenile halls and camps, which had a history of problems so severe that the U.S. Justice Department was compelled to intervene.

Powers says his two new assistant chiefs, outwardly, couldn’t be more different.

“She’s like a tiny little dynamo,” he says. “She talks fast, she walks fast, she works fast. Everything about her is fast.” Meyer, on the other hand, is “a beast,” Powers says, a “barrel-chested” weightlifter who’s competed in and won international law enforcement competitions.

“It’s ridiculous when they stand side-by-side,” Powers says with a laugh. But both, he adds, share this in common: “They get things done.”

Of the two, Perez will certainly play a more visible role—even beyond her TV spots—given the rising concerns and controversy over the potential impact of AB 109 on public safety.

In recent months, two high-profile crimes were allegedly committed by suspects sent to the county for supervision after serving prison terms for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. Under the new law, prior criminal histories are not considered when determining an inmate’s post-release supervision, except for high-risk sex offenders, sexually violent predators or “mentally disordered” offenders, who remain under state supervision .

In December, one of the county’s new wards was charged with a quadruple murder in Northridge. Then, just last week, another was named as the prime suspect in the kidnapping and sexual assault of a 10-year-old girl. He remains at large.

Critics of realignment have suggested that such crimes might not have been committed had the state not hurriedly foisted AB 109 on the counties—a contention disputed by most law enforcement officials, including Powers. He says that in 2010, the year prior to AB 109’s passage in Sacramento, more than 170 men were arrested in Los Angeles County for murder while under the supervision of state parole officers.

“If you take 11,000 offenders from the state and put them in Los Angeles County, you can predict that a portion of those offenders are going to kill people and you can predict that a portion are going to rehabilitate themselves and never get in trouble again,” Powers says. “So whatever your philosophical perspective, you can make a prediction and be right because the population we’re dealing with is so large. Having said that, the question is: Can we handle this population with better outcomes than the state?”

Perez says the disclosure that the alleged Northridge gunman was an AB 109 offender came during her first weekend on the job. Some of the probation officers, she says, were shocked because they’ve been mostly accustomed to dealing with lower-level offenders. Not her.

“In parole, this was a regular occurrence. You literally become accustomed to it,” she said the other day from the department’s drab and dated Downey headquarters. “Whether you’ve got a parole agent watching you or a county probation officer watching you, you’re going to commit a crime if that’s your intent.”

She says she tells her probation officers that a good number of the offenders they’re now responsible for supervising were once under probation’s watch for less severe crimes. “The only difference,” she tells them, “is that they’re a little older, their rap sheets are longer and they’re more sophisticated. But it’s the same population you dealt with.”

Perez says she also wants to assure the public that her agency “is ready to take on this challenge. We’re familiar with this population in terms of their risks, their needs and what we need to do to assist them in their reintegration into the community, realizing there’s always going to be some who are either not ready or not amenable to the resources and interventions we can provide to them.”

Perez says was one of her biggest challenges is how the agency can quickly build an infrastructure to handle the new supervision demands, ranging from training and hiring scores of new probation officers to modifying computer systems to improve tracking of the county’s new charges and their progress—or the lack of it.

Also at the top of the list is the screening and training of 100 probation officers who’ll be given guns, a first for the department.

“When I was a parole agent, I carried a caseload and I carried a gun,” Perez says. “The job was to make random house calls in the evenings, during the day, on weekends. And to go into some of those communities that are sometimes dangerous, gang infested, they are just not the safest places in the world. So if there’s an expectation that probation officers are going to do this, you have to give them the tools.” So far, she says, 28 probation officers have been cleared to carry firearms.

Perez says one of her other challenges, on a personal level, will be to find time to continue her practice of Bikram, or “hot,” yoga—27 postures practiced in a room with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. Perez, a youthful 50-year-old, acknowledges that she practically vibrates with energy.

“You should have seen me before I started yoga,” she says. “It helps me refocus and keep my calm. It gives me a chance to go on autopilot and think about nothing.”

Even if it’s only for a couple of hours.

Posted 4/4/13

Where farm meets park

February 28, 2013

Gordon Pawlowski didn’t know what to expect when he tied on his apron in anticipation of Grand Park’s first-ever farmers’ market on Tuesday. It didn’t take long to find out.

“We sold out at 12:30 p.m.,” said Pawlowski, chef and owner of Lenny G’s, a Cajun eatery. “I had to turn away a line of 30 people.”

The market will be held every Tuesday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. between Broadway and Spring Street, just in front of City Hall. At the inaugural event, 22 vendors were selling berries, flowers, crafts, exotic spices and teas, baked goods and prepared foods like Pawlowski’s popular po’ boys. Julia Diamond, Grand Park’s programming director, said organizers started small on purpose.

“At its core, a farmers market is about supporting independent business owners, small farms and local vendors,” said Diamond. “My biggest concern is for them, because they take the risk in coming there.”

The event drew an estimated 1,500 people—a mix of workers from adjacent buildings, passers-by and local residents.

“It went gangbusters,” said Diamond.

Fresh produce lured Carolyn Lifsey and Monica Roache away from their work at MOCA, about six blocks away on Grand Avenue. They learned about the event from Grand Park’s Facebook page. (Grand Park also is on Twitter.)

“The walk is actually kind of nice,” Roache said. “Being that it’s in the park, it offers a really tranquil ambiance for lunchtime.”

Others, like downtown worker Henry Chisom, said they were hoping for a bigger selection and smaller prices. He also hopes to see some music added to the mix.

He may be in luck.

Given the success of the trial run, Diamond plans to expand the market to meet the demand. (“We will have more farmers next time,” she said, referring to the fact that only a handful of produce vendors were selling on Tuesday.) Also, on alternating Tuesdays through the end of May, Lunchtime Concerts in the Park will add live music and food trucks on the block between Grand Avenue and Hill Street, effectively activating the whole park.

Other than the farmers’ market, relatively few organized events have taken place in Block 4—a grassy, expansive section of park. Diamond was jazzed to see the area bustling with activity.

“It’s such a big space,” she said, “that it takes the right kind of event.”

Posted 2/28/13

Senses mingle in Grand Park

February 6, 2013

“I was just walking back into the Metro station when I heard the music and smelled the fried chicken,” explains Stefanie Hamlyn, a theatre teacher from The Webb Schools in Claremont.

And just like that, Grand Park made another new friend.

Hamlyn had just finished escorting students on a field trip to the Music Center when she stumbled across the first installment of “Lunchtime Concerts in Grand Park,” a series that pairs live musical performances with savory delights from L.A.’s famous gourmet food trucks.

The events will take place between noon and 1:30 p.m. on alternating Tuesdays through May. They’ll feature new tastes each time along with an eclectic mix of local music—including opera, jazz, Latin, rock and “singer-songwriter” styles. Along with the park’s popular lunchtime yoga series, the concerts are designed to attract workers from nearby buildings and catch the attention of passers-by like Hamlyn, says Julia Diamond, Grand Park’s programming director.

“We are really aiming to make midday in Grand Park a wonderful experience on a regular basis,” Diamond says.

Judging by Tuesday’s turnout, they’re off to a good start. Despite dreary skies and temperatures in the 50s, dozens of children ran around as an audience watched the 5-piece Colburn Brass ensemble and workers enjoyed lunch breaks in the park’s signature pink chairs. Lines for the food trucks stretched 30 long. It was an encouraging sign for Diamond, who notes that “Angelenos aren’t known for being the toughest when it comes to cold weather.”

Meanwhile, Hamlyn was happily absorbing her first experience in Grand Park, excited to see a slice of green downtown.

“It’s much better than it used to be,” she says, referring to the drab patchwork of concrete and grass that used to dominate the location.

As the weather warms and more people become aware of the park, Diamond says, she’ll be custom-tailoring events, including integrating dance performances into the mix. When summer hits, Diamond plans to create events using the remodeled Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain and its new membrane pool, in which guests are encouraged to splash.

For Aaron Wilson, a 40-year-old musician from Silver Lake, Tuesday’s event was already a bit too busy for his schedule.

“I always wanted to try Ludo Truck but the line was too long,” says Wilson, referring to the mobile eatery owned by Ludo Lefebvre, star of cooking shows like Top Chef and The Taste. Luckily, there was another option—the Gourmet Genie, which offered Mediterranean fare.

While Hamlyn sat, waiting for her chicken to reach a crispy brown from the Ludo Truck, she considered other ways to enjoy the park.

“My husband and I come down for the symphony all the time,” she said. “We live next to the Gold Line but never took Metro because we were afraid to walk that short distance to the Disney Hall. Now, I’m thinking maybe we can.”

Posted 2/6/13

Noontime Namaste

January 3, 2013

Christel Joy Johnson's yoga class has become one of Grand Park's most popular programs. Photo/Javier Guillen

Christel Joy Johnson has a resolution for all you desk-bound downtowners: Come see her at lunchtime—and breathe.

Since November, Johnson has been leading one of the most popular public programs at Downtown Los Angeles’ new Grand Park, a free lunch-hour yoga class. The free 45-minute sessions have been drawing passersby, office workers and downtown hipsters, who’ve gathered by the score in a performance space between Grand Avenue and Hill Street for the gentle midday workouts, even in inclement winter weather.

“We thought we’d get maybe ten people,” Johnson says laughing. “The first time we held the class, 50 people showed up.”

Since then, she says, the classes—at 12:15 p.m. on Wednesdays and Fridays—have averaged 30 to 40 students.

“It’s everybody from county workers on their lunch break and Music Center employees to people who come by bus or walk over from apartments and bring their yoga mats with them,” she says.

“It’s getting so I’m starting to see some of the same faces. There are two girls in the front who live downtown and have been there for every session. I imagine with New Year’s resolutions we’ll get even bigger when we start up again on January 9.”

The Wisconsin-born Johnson, 39, didn’t set out to become the unofficial yogi of a major metropolitan civic center. Like so many in L.A.’s service sector, she came here to act.

Arriving in her mid-20s with a degree in theater arts from San Francisco State, she says, she gravitated toward small ensembles; she is currently a member of the local theater group Ghost Road Company. Work as a production assistant on films and at the Music Center helped underwrite her stage career, she says, “but theater doesn’t pay a lot, so I had to do other jobs to pay the bills.”

One of those other jobs was yoga, which she had taken up while she was a student to help mitigate the lingering effects of an assortment of old back injuries.

“About six years ago,” she says, “I became really serious about it, and in 2009, I did a 3-month teacher training at the YogaWorks in Larchmont Village, where I had taken some classes.”

At first, she says, the intensive training was a personal challenge and a means of coping with a series of illnesses in her immediate family. Over time, however, she found she enjoyed the challenge and the personal contact.

She’s taught in fitness centers, community classes and for private clients. But for all her skill at saluting the sun and assuming the “downward dog” position, it was her theater network that led to the Grand Park gig. From the outset, park programmers had talked about yoga classes as a way to entice the brown-bag lunch crowd away from their desks and into the fresh air.

“I’d been a part-time production assistant at the Music Center for eight years,” she says, “and the Music Center does the programming for Grand Park. When they decided they wanted to do yoga classes, and that they wanted to produce something themselves rather than team up with a studio, someone mentioned that I taught yoga and they approached me.” Though the classes are open and free to the public, the Music Center pays Johnson for her time.

“I love it,” she says simply. “You’re outside. You have the sky and the trees. Hummingbirds fly around the group as we do our class. And it’s really cute—people in business suits at the Starbucks will often take in our energy as they sit there watching. One day, a group of ladies in very nice clothes was just quietly doing yoga with us in their chairs.”

About a third of the group is male, she says, and ages range from twentysomething to seventysomething. Most, though, are middle-aged beginners who appreciate her ability to help them tailor the positions to build flexibility.

“As someone who loves yoga and thinks it’s a beautiful thing for the community, I hope the program grows,” Johnson says, noting the success of other outdoor programs such as the free daily yoga in Hollywood’s Runyon Canyon Park.

For now, she and her students are just glad that the lunch-hour yoga has been extended for another quarter. “It’s probably not going to lead to acting jobs,” she says, laughing. “But that’s not why I do it.”

Posted 1/3/13

A giant step for L.A.

November 18, 2012

Margot Ocañas, the city’s new pedestrian coordinator, at the intersection of Wilshire and Fairfax this week.

In some ways, Margot Ocañas has been walking the walk ever since she was a kid growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and her mom sent her off to modern dance lessons with the words:

“You’ve got two feet and a bicycle. Get going.”

Talk about prophetic. Today, Ocañas—a Mandarin-speaking Fulbright scholar and one-time Wall Street analyst whose resume also includes running an independent film company with her husband and developing “streets for people” projects at the county Department of Public Health—is jumping feet first into a brand new role with major ramifications for how L.A. moves into the future.

As Los Angeles’ first pedestrian coordinator, Ocañas, 48, is front-and-center of a growing movement that aims to rethink streets as we know them.

Her appointment is just the latest sign—along with car-free CicLAvia events, a new pedestrian plaza in Silver Lake and a burgeoning public transit system—of how Los Angeles is throwing off its car-centric reputation in sometimes unexpected ways.

“The national momentum is very much our friend right now,” Ocañas said. Pedestrian awareness is “part of a larger national conversation. People are in tune with that.”

Ocañas and assistant pedestrian coordinator Valerie Watson, an urban and regional planner by training, have recently joined the city Department of Transportation. Their mission: making life better for walkers on streets that often were built mostly to enable automobiles to get from Point A to Point B as efficiently as possible. The tools of transformation include reshaping lanes and crosswalks, changing signs and signals—anything to foster calmer corridors and reduce the “raceway mentality” that’s rampant on many streets.

And then there are those things that are beyond the DOT’s purview—such as “street furniture” like benches and light fixtures. “To enhance the safety and the warmness of a corridor, you might want to start installing more of what I call human scale lighting. You may have flower baskets, or trash cans,” she said. “I think it’s those types of amenities that just make it feel more like an outdoor living room.”

Since sidewalks and street furniture fall under the Bureau of Street Services, not the DOT, part of her job involves reaching across departmental lines. “There are just increasingly strong strategic working relationships and partnering that’s happening with Street Services and Street Lighting,” she said.

Deborah Murphy, founder of the pedestrian advocacy group Los Angeles Walks and chair of the city’s Pedestrian Advisory Committee, said she’s been urging the appointment of an L.A. pedestrian coordinator for more than 15 years. While Los Angeles still has a long way to go to before it catches up with other cities including, locally, Santa Monica, she senses a permanent transformation is underway.

“I have really seen a huge change in the last year,” she said. “I’m thrilled. I think Margot and Valerie bring lots of great energy to pedestrian safety, and to encouraging people to walk.”

The well-traveled Ocañas, who moved to Los Angeles in 2003 from New York by way of Austin, also thinks the moment is right for the city to get in touch with its pedestrian side. She’s reached out to counterparts who are on the same journey in New York, which is regarded as a national leader in reconfiguring streets, notably in Times Square, as well as in San Francisco and Chicago. She thinks it can’t hurt that stratospheric gas prices are making alternative modes of getting around look better and better these days.

“Selfishly, I’d love to see gas prices not go down,” said Ocañas, who gets to work by bike, bus and foot three days a week and has organized a “bike train” caravan to get her two children to school each morning. “I could be talking till I’m blue in the face but there are certain triggers that just force behavioral change.”

Walk a mile in her slingbacks, and you’ll quickly get a sidewalk-level view of what’s good, bad and ugly out there on the L.A. pavement.

At the busy triangular intersection where Fairfax, Olympic and San Vicente come together, Ocañas watched one morning this week as pedestrians scrambled to cross. She reflected on how broad streets with short signal times can pose difficulties, especially for the elderly.

“I have seen situations where seniors are caught three-quarters of the way across the street and the light has turned,” said Ocañas, who lives in the neighborhood with her family. “We do have a population that’s getting older. We need to adjust signaling to ensure their ability to cross more effectively.”

Beyond that, “unwelcoming” streetscapes can send a forbidding signal to just about anyone who’s not in a car.

“People are not incented, or motivated, or enthused at times to get out and walk,” she said. “But those times are changing.”

Her proposed solution: “Re-engineer the environment.”

Ocañas’ previous position as a policy analyst at the county Public Health department’s Project RENEW, funded with federal stimulus dollars, involved working on grant proposals intended to combat obesity by confronting challenges in L.A.’s “built environment”—such as those long, unshaded stretches of roadway where fast car traffic and widely separated crosswalks make it uninviting or impossible for pedestrians to stroll and interact.

“When I was on the health side, we always talked about, ‘We’ve built ourselves into sickness so we need to build ourselves out of sickness,’ ” Ocañas said. One of the projects she worked on turned into the green polka-dotted Sunset Plaza Triangle pedestrian zone in Silver Lake, which opened in May.

Her own transformation, from a career in the private sector that included working at Dell Computers, started modestly enough, with a block party closure she organized to give neighborhood kids a chance to wheel around freely on their bikes and scooters. Ryan Snyder of the urbanist transportation planning firm Ryan Snyder Associates was there as the guest of a neighbor. When he met Ocañas, he mentioned the upcoming policy analyst positions in Public Health.

A light bulb went on. “It never occurred to me to consider taking a recreational passion and translate it into a paying job,” she said.

At the city Department of Transportation, Ocanas’ and Watson’s first priority is developing a Safe Routes to School Strategic Plan for the city. The “data-driven” plan will help the department prioritize spending on student safety projects and will introduce “new types of pedestrian-centered amenities” into the mix. It also will serve as a building block for the eventual creation of a “Pedestrian Safety Action Plan” for Los Angeles—something that’s probably three to five years down the road.

At the same time, they’re working to foster innovative “place making,” including “parklets” (tiny curbside areas the size of parking space, often in front of businesses and furnished with seating areas and plants) as well as bike corrals and pedestrian plazas like the one in Silver Lake.

“You do these things that you can quickly implement with low-cost materials…to help demonstrate the benefits of ‘people-space,’ ” Watson said.

Ocañas, who like Watson is being paid by DOT Measure R funds that have been targeted for pedestrian initiatives, said she’s finding the department a “very supportive environment.”

“I actually find them very open,” she said. “We will debate. I will learn from them: ‘OK, you just can’t do that, and for these reasons.’ But similarly, they are very open to ‘Why not?’ ”

Posted 10/18/12

Poll work’s all in the (county) family

November 8, 2012

It was closing in on 10 p.m., and Russ Guiney had an after-hours drop to make in a church parking lot in Arcadia.

While his day job involves running the county Department of Parks and Recreation, on this particular evening Guiney was helping to transport precious cargo—ballots from one of the county’s 4,621 polling places—to the trucks waiting to take them to their final destination, the Registrar-Recorder’s office in Norwalk.

It takes an army to put on an election in a county as vast as Los Angeles, and many of the foot soldiers are county employees.

On Tuesday, 3,946 of them—from clerks to department heads—marched into action as voluntary poll workers, part of a larger group of 27,000 community and student workers needed to pull off a presidential election in which more than 2.3 million county residents cast ballots.

If you voted on Election Day, chances are you ran into one of them. Maybe they provided a tutorial in using the InkaVote machine—or even gave you a round of applause.

“A lot of the memorable moments came from the first-time voters who came in,” said Reggie Tuyay, a recreation service supervisor at Whittier Narrows Recreation Area who worked a polling place in South Pasadena on Election Day. “One of the things our table did is we started applauding the first-time voters.”

County workers must get approval from their supervisor in order to participate. High-ranking managers are required to take part or to recruit 5% of their workforce to do so. Everyone receives their regular county pay for the day, in addition to a stipend ranging from $105 to $175, depending on their assignment.

And there are some rewards that go beyond the financial.

“It was my first time doing it, and I really enjoyed it,” said Analie Pitallano, who ordinarily works as a victims’ advocate in the District Attorney’s office. “I loved seeing immigrants who’d just become citizens come in to vote. It was just so great. Parents brought in children to show them the process.”

It’s not a cushy job—at least as far as the hours are concerned, with workers arriving before polls open at 7 a.m. and staying after they close at 8 p.m. to inventory the ballots and pack them up, along with the election equipment.

“When we got out at about 8:45, we found out that Obama had already won,” Pitallano said, who nevertheless said she’d happily do it again, in large part because of the interactions with the voting public.

“It was a long day, but I met so many people,” added Annie Luong, an administrative support staffer in Health Services.

“If you’re a people person, this is the job for you,” said Jacklyn Jorge, the program’s coordinator.

For the Registrar-Recorder’s office, bringing in county employees—under a program established by the Board of Supervisors in 2001 to combat chronic shortages of poll workers—has become an important part of staging elections across a sprawling territory.

“I think it’s become an essential part of our process because the county is so large,” said Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk Dean Logan.

It also provides a large pool of county-affiliated election observers. “It gives us the opportunity to hear from the county family what is going on out there,” Logan said.

And sure enough, the day after the election, department heads including Santos Kreimann of Beaches and Harbors, who’s currently serving as acting director of the county Assessor’s Office, were coming up to Logan to share what they’d seen.

Kreimann and Guiney, the head of Parks and Recreation, both said they welcomed a chance to spend a day working on the front lines of democracy—and getting the change in perspective that goes along with it.

“I enjoyed it, actually, because I wasn’t in charge,” Kreimann said.

Posted 11/8/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink