Road warriors get ready to rumble

February 1, 2011

The switchbacks and hairpins of the Santa Monica Mountains have lured thrill seekers for generations. But starting this spring, Los Angeles County will be throwing speed demons a new kind of curve.

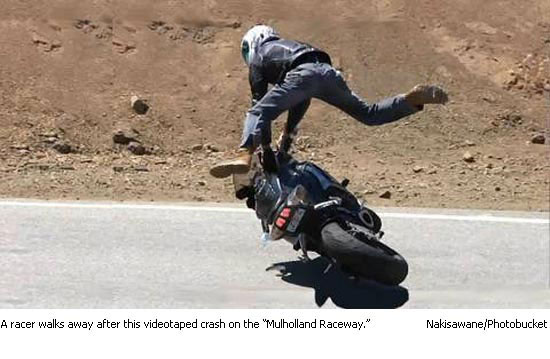

After years of study and preparation, the Department of Public Works will soon be installing speed-deterring “rumble strips” down the center lines of one of the most popular and storied amateur racing loops in Southern California: the section of the so-called “Mulholland Raceway” that starts and ends at Mulholland Highway and traverses Stunt, Schueren, Piuma and Cold Canyon roads.

The move comes at the behest of local homeowners, who for years have sought relief from the rip and roar of the high-performance sports cars and motorcycles that race through the canyons day and night. Over the years, authorities have tried various solutions, from increased traffic patrols to seizing the vehicles of illegal street racers, but the practice has persisted.

California Highway Patrol Officer Leland Tang says the patrol area around the Stunt-Piuma loop has averaged nearly 40 traffic collisions a year for the last several years. The collision average has been about 50% higher on the west side of Las Virgenes, Tang says, but the outcry on the east side has been more concentrated because that area is more densely populated. (Click here for a map of the loop.)

“It’s scary just to go to your mailbox,” says Mary Ellen Strote, who has lived near the top of Stunt Road since 1981.

Some are just Sunday drivers and law-abiding enthusiasts, she and other homeowners say, but too many others are revved-up young men testing their machines and their mettle.

“The tailgating, the passing on blind curves, the aggression,” Strote says. “You’ll be driving along, and there’ll be a bicyclist on one side and a motorcyclist in the other lane and then here will come some insane person, passing on a blind curve.”

Those curves—blind and otherwise—are the targets of the rumble strip project, says Todd Liming, senior civil engineering assistant at the county Department of Public Works.

During the past decade, residents have complained that street racing in the area has become an increasing danger, as drivers and motorcyclists—especially the inexperienced ones—have sought to shave seconds by cutting corners and darting across the center line in and out of oncoming traffic. Some race in packs, warning each other of law enforcement via text message and cell phone. Some yearn to emulate professional test drivers.

Strote and others say Stunt Road has become particularly popular because outsiders think—incorrectly—that it was named for Hollywood stunt drivers. (In fact, the road was named for the Stunt family, homesteading fruit-growers whose nearby ranch is now part of the University of California Natural Reserve System.) Over time, pressure has grown to find fresh solutions to the ongoing concern.

Initially, Liming said, area residents urged speed humps as a way to discourage racing, but humps posed too big a safety risk on the hilly and winding roadways. Improved signage helped, as did stricter enforcement, which was ramped up over the years as part of Operation Safe Canyons, a state and local task force led by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office.

But traffic mitigation is particularly difficult in mountain areas, says Liming. And patrols can only do so much in an area as vast as the Santa Monica Mountains, Tang adds. Finally, after several years of study, county engineers came up with centerline rumble strips – sections of small grooves cut directly into the asphalt – as a possible way to deter corner-cutting, drifting and other dangerous aspects of what amateur racers call “canyon carving.”

The indentations, which are 5 inches wide and a little less than a half-inch deep, literally and figuratively underscore the double yellow line that separates lanes of opposing traffic.

Used for years along the sides of highways elsewhere to warn drowsy motorists that their cars might be straying onto the shoulder, rumble strips along the center line offer a similar warning to cars and especially motorcyclists who stray toward the middle of the road, rather than its edges, Liming says. The strips create an intense, unpleasant vibration when tires hit them and alter the road surface just enough to force cyclists to slow down in the event they decide to cross them—especially at high speeds and at an angle.

The solution is not without its own possible downsides. Although centerline rumble strips have been used successfully in other areas—the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, for example, credited them last year with a 35%-50% reduction in crashes in areas on which they were installed—any change in the road surface can create hazards, especially for bicyclists and motorcyclists.

And homeowners may be trading one form of noise pollution for another: When tires hit the strips, however they’re positioned, it’s loud.

“This is a pilot project,” says Liming, who stresses that county engineers will be closely monitoring the effort. If the strips work, he says, they will eventually bisect the entirety of the 14.5-mile loop except for a short section on Mulholland Highway. This might lead to their use in other race-plagued roads in the area. The project is expected to cost $425,000 to $475,000, though federal grants are covering most of that price tag. The initial phase, put out to bid late last year, is expected to start in April.

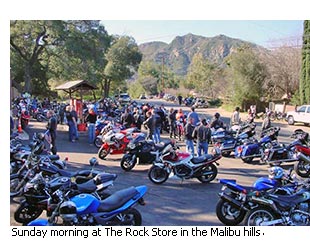

The plan drew mixed reviews on a recent day at The Rock Store, the popular Mulholland Highway restaurant and biker hangout.

“What?! No way!” exclaimed veteran motorcyclist Scott Storey, a 53-year-old Canadian who says he’s been riding since the age of 15 and is still recovering from a fall on a blind curve that wrecked his Ducati in July. Storey expressed concern that rumble strips anywhere on the road might pose an accident risk to an inexperienced rider. He says that once a motorcycle loses traction, especially while leaning into a curve, only the most skilled can keep from crashing.

Pulling a camera from his pack, Storey shared some videos he’d just taken of rides along Stunt and Piuma, using a lens strapped to his chest. They provide a rider’s-eye view of the curving roadway and sheer cliffs along the loop, and illustrate the difficulty of negotiating these roads quickly.

“I figure if you can’t stay on your side of the road, you can’t drive very well,” says Storey. “I figure its best to live to ride another day. But some people, their idea is to get down the road as fast as possible to feel like a big man. And the fastest route is to ignore the double yellow lines.”

“It’s not gonna stop ‘em,” agreed Malibu photographer Paul Herold. “It’ll discourage the bikes, but the bikes aren’t crossing the double yellow anyway—anybody on two wheels up here will tell you that the first rule of canyon riding is to never cross the double yellow. The cars, though—the cars aren’t gonna slow down.”

Other enthusiasts, however, thought rumble strips might be worth trying.

“I used to live off Latigo Canyon in the 1970s, and there would be nobody when we’d ride, but it’s too congested now,” says Kaming Ko, a 56-year-old former motorcycle and auto racer who lives in Woodland Hills.

“You can’t change what people do, but you can discourage them from doing something stupid. They’re still going to go fast, but maybe this will help them maintain some integrity and get them to stay in their own lane.”

Posted 2/1/11

Our night on the streets

February 1, 2011

I’m often asked if there is a public will in Los Angeles to do anything about homelessness.

I’m often asked if there is a public will in Los Angeles to do anything about homelessness.

The answer came through loud and clear last week when more than 200 volunteers showed up in Hollywood for the biennial homeless count in Los Angeles County. Those of us taking part in the Hollywood count were playing a role in a nationwide effort aimed at identifying the number and location of homeless persons living on the streets.

The purpose is simple: If we are going to address homelessness, we need to know where to target our limited resources. The homeless count gives us a road map to make a real difference on this vexing issue as we move toward a goal of providing permanent supportive housing to the chronically homeless—those who have been on the streets for at least a year.

All across the region last week, groups like ours assembled around 9 p.m. and got our marching orders for the night ahead. Each team was assigned a territory and given some simple rules of engagement: keep a respectful distance and don’t interact with the people you’re counting; use your flashlight to light up your tally sheets, not those you’re tallying; and use caution and common sense in navigating the streets at night.

I had lots of company out there. Thousands mobilized to help with the federally-mandated count, administered here by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Among the volunteers were members of my staff. I’d like to share a few of their impressions with you here.

One of my deputies joined the counters in his hometown of Santa Monica. He came across people living in cars in the parking lot of a busy family restaurant—a sight that might have gone unremarked during the daytime. He also was struck by the juxtaposition of wealth and poverty, such as the homeless pair encamped just 50 feet from a trendy Italian bistro where patrons drop $200 on a dinner for two with wine.

The night-time trek, he said, definitely made him see his city in a new way.

Another deputy, who had taken part in the Santa Monica count in 2008, noticed a marked decrease in the number of homeless people on the same blocks this time around. That may be the result of Santa Monica’s efforts with the county to provide housing along with the services necessary to address the issues that render people homeless in the first place.

This deputy was struck by the homeless prevention measures she saw in place: trash dumpsters fenced off and locked, bright lighting, locked apartment and condo garages off the alleys, and less accessible areas to loiter. Overall, the city seemed clean and shiny, which made it even more heartbreaking to see homeless people huddled on sidewalks in worn sleeping bags or torn-apart cardboard boxes.

In West Hollywood, one of our staff teams wondered what and who they would encounter in their assigned tract—which included landmarks as various as the Mondrian Hotel and Barney’s Beanery. Their night of surveying began and ended with the two people they observed huddled under a blue tarp in a drugstore parking lot. A sheriff’s deputy accompanying our staffers knew the pair well. He said they’d come out to California from the Midwest years ago, eking out a living by recycling. They’d had run-ins with the law over their methamphetamine use, he said, and so far had rebuffed offers of help from the agency PATH (People Assisting the Homeless.)

Another 3rd District team hit the streets in Van Nuys. One of their experiences illustrated a challenge inherent in our assignment: who exactly should be counted as homeless, based on sight alone? Was that man in the hooded sweatshirt homeless—or just someone walking aimlessly through the neighborhood? When our team spotted the same man 10 minutes later, this time pushing a shopping cart loaded with possessions, the question was answered. He became part of the tally.

It will be months until the final results of the count are in. But one thing is already clear: Last Thursday night, the main room at the old Hollywood Municipal Building was bulging with people, enthusiasm and commitment. Despite the difficulty of the task, the scene of hundreds of people participating in a homeless count into the wee hours of the morning provided a rousing answer to anyone who doubts our community’s commitment to addressing homelessness.

Posted 2/1/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information