D.A. sees new day for mentally ill

District Atty. Jackie Lacey tells the Board of Supervisors that jail diversion is “right within my mission.”

When Jackie Lacey won election as district attorney in 2012, no one expected the county’s chief prosecutor to become a crusader for taking people out of—rather than into—jail.

Yet this month, she was again center stage before the county Board of Supervisors to push for sweeping, if gradual, reforms to provide the mentally ill with alternatives to incarceration.

“Too often, our default position is to lock mentally ill people away because of a perception that there is no alternative,” Lacey said. “Well, there are alternatives — we just need to dedicate resources to expanding the capacity of those alternatives.”

Flanked by leaders of the county’s criminal justice system and social safety net, and with advocates for the mentally ill sitting in the audience, Lacey vowed to present a comprehensive report on diversion programs in early 2015.

She emphasized that initial goals for the Criminal Justice Mental Health Project should be “modest and achievable.” Progress, she said, would take time.

“I want to temper our expectations for a quick fix,” Lacey told the board, pointing out that the county is so large and complex that it’s “a country unto itself.”

Still, there is a sense of urgency to the undertaking, not just for mentally ill inmates whose conditions are worsening behind bars. The U.S. Department of Justice has accused the county of failing in its constitutional duty to adequately serve mentally ill inmates and will likely force the county into a court-supervised federal consent decree.

Although the board is weighing a $1.7-billion proposal to replace Men’s Central Jail with a Consolidated Correctional Treatment Facility, envisioned as “a treatment facility for inmates, construction won’t be completed for years.

The county does have diversion programs already in place for the mentally ill but none has the capacity to serve the vast numbers of people whose schizophrenia, paranoia, bipolar disorder and other conditions may cause them to run afoul of the law. An estimated 15 percent of county’s 20,000 inmates have been diagnosed with a mental illness.

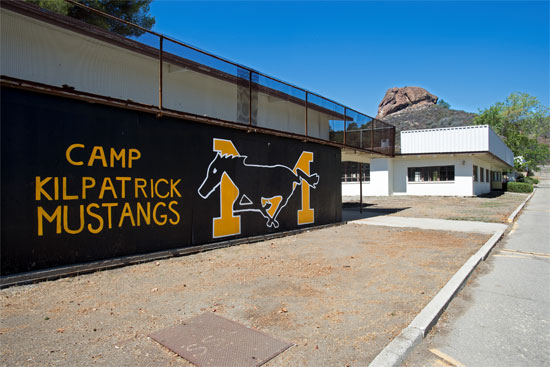

A pilot program was recently created to provide permanent supportive housing for 50 chronically homeless, mentally ill people who’ve been arrested for low-level offenses in the San Fernando Valley. Championed by the office of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the Third District Diversion and Alternative Sentencing Program is envisioned as a potential template for diversion programs countywide.

Currently, the Department of Mental Health has only three psychiatric urgent care centers and three crisis residential treatment programs across the 4,000-square mile county, and 30 mobile crisis support teams to respond to emergencies, sometimes while partnered with sheriff’s deputies or police officers.

Thanks to a $40.1-million state grant, however, those services will soon be expanded. The board voted to double the number of its urgent care centers, and potentially multiply its crisis residential treatment programs tenfold. It authorized creating 11 more mobile crisis support teams.

In an interview, Mental Health Director Marvin Southard said only those who are not considered a danger to society would be eligible for diversion.

“If somebody has committed a serious crime, they need to pay the consequences,” he said. “Whether they happen to be depressed is really beside the point.”

DMH also has mental health professionals embedded in 22 courthouses, but Lacey acknowledged that some prosecutors and public defenders don’t utilize their services or even know they exist.

She said officers of the court, as well as law enforcement officers, need additional training to ensure the mentally ill receive treatment, instead of ending up behind bars. She said that training would be the “short term” goal of the Criminal Justice Mental Health Project.

County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky believes that having Lacey spearhead the county’s diversion efforts is a “game changer.”

“It’s one thing for a non-law enforcement officer to advocate for this sort of thing, but it’s another when one of the chief law enforcement officers in the county — in this case, the D.A. — gives this the imprimatur of acceptability,” he told her after her recent testimony.

“I think this will be a real revolution for the county,” he said. “And I hope that we have the political will to get it done.”

In an interview after her board appearance, Lacey said she sees diversion programs as being “right within my mission.”

“My mission is to seek justice,” she said. “The stories of people who have loved ones in jail, or who have been put in jail themselves while mentally ill, just speaks to me personally.”

Posted 11/20/14