Valley date with CicLAvia [updated]

It’s been downtown, to East L.A. and to the beach, but one major part of town—the sprawling and populous San Fernando Valley—has been left out of the CicLAvia fun. All that changes on March 8, 2015.

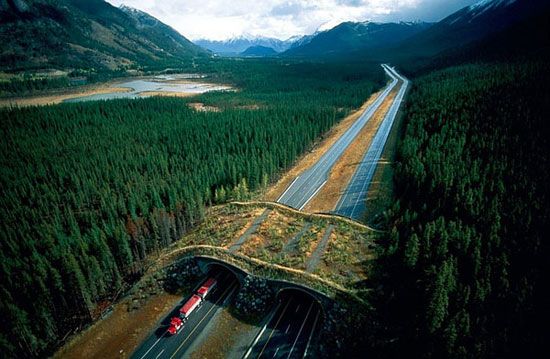

That’s when the hugely popular open streets event is set to roll down two well-known Valley thoroughfares, Ventura and Lankershim boulevards. The car-free route now being finalized will stretch down Ventura from Coldwater Canyon to Lankershim, then dog-leg north on Lankershim to Chandler Boulevard, where Metro’s Orange and Red lines meet.

Zachary Rynew, who serves as a volunteer “bike ambassador” to the Valley for the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, said the event will energize cyclists in a community that traditionally has lagged behind areas of the city where bike culture has more fully taken hold. With its flat, wide streets, the Valley is ripe to emerge as a cycling hot spot, Rynew said.

“CicLAvia is really going to be an eye-opener,” he said. “The Valley can work at a bicycle scale, it’s just that people need the confidence to get out there on the streets and feel comfortable.”

Aaron Paley, CicLAvia’s co-founder, said details of the event still need to be worked out, but outreach to community and business stakeholders already is underway. Two weeks ago, he and his staff pedaled the route themselves to get a street-level view. Paley plans to continue engaging the community over the next few months before releasing a formal announcement, complete with maps, around the beginning of 2015.

The route’s nexus with major transit lines and bike paths along the Orange Line, Chandler Boulevard and parts of the L.A. River is intended to make the event convenient and accessible for cyclists, pedestrians, skateboarders, scooter-riders and hula hoopers who want to spend the day car-free.

“When we thought about doing the first one in the Valley, I really wanted to pick up on the infrastructure,” Paley said. “We planned it around the Red and Orange lines.”

Buses and trains will play a big part in moving people to and from the Valley CicLAvia, which is expected like previous events to attract more than 100,000 participants. Avital Shavit, project manager of Metro’s open streets program, said transit accessibility was one of the key criteria evaluated under a grant program that awarded the Valley event $366,773 in June.

“CicLAvia has had a direct effect with promoting ridership on Metro,” Shavit said. On the Red and Purple subway lines, she said, “ridership has gone up an average of 25% on the day of CicLAvia events over the past three years.”

She added: “It’s a way to get people to try Metro for the first time. They’re coming to a car-free event and thinking ‘How are we going to get there?’ One great way is by taking Metro.”

The event’s route will pass by major entertainment landmarks like Universal Studios and interact with community staples like the Studio City Farmers Market. Additionally, CicLAvia’s Paley wants to focus on the resurgent waterway that runs through part of the route. “I want to do something related to the revitalization of the L.A. River in the Valley,” Paley said, referring to greenway projects that have made major bike, pedestrian and environmental improvements to sections of the river.

For people like the bike coalition’s Rynew, a 30-year Valley resident, the most exciting prospect is being able to show certain people what they’ve been missing.

“The great part of CicLAvia is that you get to showcase your neighborhood to the rest of the city,” Rynew said. “The last three years has been the most exciting time in the Valley’s development, with the NoHo arts district and all these great restaurants going in on Ventura Boulevard. I think people that are afraid to go over the hill are going to see the Valley in a whole different light.”

Updated: 8/22/14: A spokesman for Los Angeles City Councilman Paul Krekorian emphasized Friday that the date for the proposed San Fernando Valley CicLAvia, provided by the organization’s executive director, has not been finalized and could potentially change in the weeks ahead. There could also be revisions in the route as input is sought from neighborhood residents and businesses, said spokesman Ian Thompson. Krekorian’s council district includes the San Fernando Valley.

Posted 8/21/14