Featured

Not just a local hero

February 6, 2014

For 40 years, Rep. Henry Waxman has represented a wide swath of Los Angeles’ Westside. But the truth is that no single member of Congress has had a more far-reaching impact on the health and well-being of the entire nation than Waxman.

He championed legislation that led to cleaner air and water not only in L.A. but also in polluted cities across America. He was the driving force behind bills that restricted the use of pesticides and required food manufacturers to put those now-familiar nutrition labels on their products. He made sure that children in lower-income families had access to health insurance. He wrote the law that created the generic drug industry, saving consumers countless millions on their prescriptions.

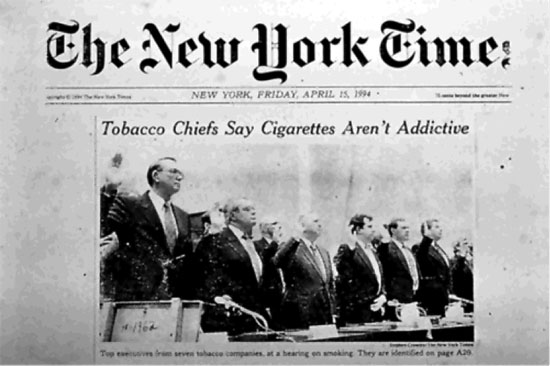

And remember back in the mid-1990s, when the heads of the nation’s tobacco companies were collectively summoned to Washington for a televised hearing, during which they denied that their product was addictive? That landmark session was convened by Waxman, and it represented a turning point in the long and ultimately successful efforts to give the federal government more power to regulate tobacco.

Although Waxman is a proud liberal Democrat, a good number of those bills—and many others—were signed into law by Republican presidents, a testament to his mastery of the legislative process and his ability to build respect and consensus on both sides of the aisle.

With that legacy of accomplishment, it’s no wonder that, in recent days, there’s been an outpouring of praise for my friend and role model, the 20-term congressman. Last week, Waxman, surprised us all when he announced that he’d be retiring at the end of this year. At 74, he explained, it was time to begin the next chapter of his life. I can certainly understand that desire on the part of someone who has devoted his entire adult life to elective office. But I wish it wasn’t so.

Waxman’s departure will leave a huge void in Congress. Among many other things, his has been a powerful voice for the positive role government can play, especially in protecting the public health, whether you’re among the most fortunate of us or those struggling at the lower rungs of the economy. It’s not an exaggeration to say that his legislative work has saved millions of lives. He will surely be remembered as a huge idealist, but one with an unparalleled pragmatic capacity to turn those ideals into reality.

He also has been a great friend to Los Angeles County. In the mid-1990s, for example, when the county was confronting bankruptcy and the collapse of its health care system, Waxman stepped in to help secure the Clinton Administration’s help. In 2008, when federal officials wanted to sell off the Veterans Administration properties in Westwood, where so many deserving men and women have received assistance, Waxman again came to the rescue.

On a personal note, no public servant has taught me more about what it takes to bring about positive change in our society. Through his example, Waxman showed me that it’s not enough to have a vision. You must be willing to stay in the ring despite the long odds you may face. And when you’re knocked down, you get up and keep fighting for what you believe in.

As one of his longtime constituents, I’m grateful for his unmatched advocacy.

He’s going out a champion.

Waxman's tobacco hearings represented a turning point in bringing greater regulation to the industry.

Posted 2/6/14

After Baca, a new start

January 16, 2014

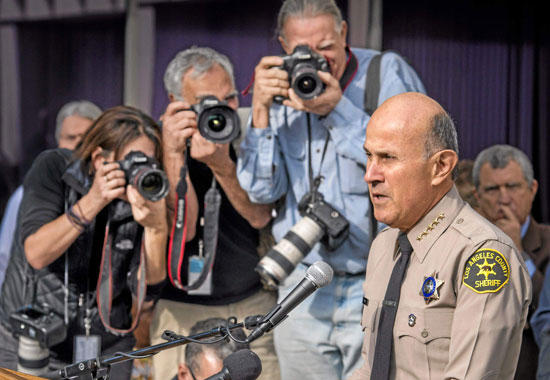

When Lee Baca announced his retirement from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, I was relieved but not surprised. As a colleague and friend, I knew he was hurting.

While preparing to seek a fifth term as sheriff, Baca had become the public face of a department rocked by scandal, including the recent federal indictments of 18 members of his force for alleged brutality, corruption and obstruction of justice. With each passing day, as his campaign opponents honed their attacks, it wasn’t only the sheriff’s re-election prospects that were taking a hit but also the department to which he’d dedicated nearly 50 years of his life.

So Baca did the right thing—the courageous thing—for himself and the agency. His voice cracking, he told a packed news conference that he was stepping aside at the end of this month. “I don’t see myself as the future,” he said. “I see myself as part of the past.” Los Angeles County voters will now have a rare opportunity to elect a sheriff without an incumbent on the ballot.

Although Baca may have removed himself as the campaign’s lightning rod, he has presented those of us on the Board of Supervisors with a huge responsibility for the department’s uncertain future. It’s now our job to appoint an interim sheriff who’ll serve until December when the newly-elected sheriff is sworn in.

To be sure, conditions within the Los Angeles County jail system have improved since allegations of excessive deputy violence began escalating several years ago, leading to the creation of a citizen’s commission that blamed top management for many of the problems. By all accounts, the use of serious force is down significantly. Still, big challenges confront the department, including how to humanely—and constitutionally—deal with the thousands of inmates entrusted to our custody, especially those suffering from mental health problems.

In the days ahead, our interviews with candidates for the interim sheriff position will begin. And I can tell you this much for sure: We should not be putting a caretaker in charge. We need a reformer who’ll build on the momentum the department has achieved since the blue-ribbon Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence concluded its widely-praised work. We need a proven leader who can resist the potential bureaucratic backsliding that can occur in an institution where change comes hard.

And we need someone who won’t be entering the growing field of candidates competing for the top job. This historic moment of transition is too important for an interim sheriff to have his or her attention diverted by a tough campaign or to think it’s necessary to build political alliances within the department’s ranks.

An interim sheriff must give his elected successor every opportunity to hit the ground running to swiftly restore the department’s reputation and repair the morale of the thousands of hard-working men and women who’ve been unjustly tarnished.

Every crisis presents an opportunity. And the voters of Los Angeles County now have precisely that—an opportunity to put their imprint on the future of the Sheriff’s Department, casting a vote for leadership that can clean house and offer a new beginning.

Posted 1/16/14

The day I met Mandela

December 10, 2013

Los Angeles City Hall has played host over the years to heads of state, visiting dignitaries and many of the world’s great and near-great.

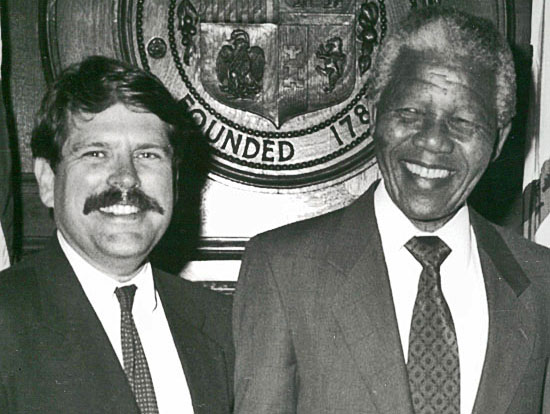

But one visit on June, 29, 1990 by a smiling septuagenarian fresh out of a South African prison stands in a class of its own.

Crowds waited hours in the sun to see Nelson Mandela, the living embodiment of the struggle against apartheid, as he came through our city on what all of us sensed was a march of destiny for his country and the world.

Mandela was introduced by Gregory Peck, embraced by Sidney Poitier and lauded as a hero by Mayor Tom Bradley. Harry Belafonte was there that day with his video camera. I’d brought mine from home, too, and we ended up videotaping each other.

The atmosphere was electric as thousands waited for a glimpse of Mandela. Some climbed trees, craning to get a better look.

Just five years earlier, while Mandela was still imprisoned on Robben Island, I had as a Los Angeles city councilman helped lead divestiture efforts that prompted withdrawal of city deposits from banks doing business in South Africa and halted some pension fund investments in companies with connections there.

Now, here was Mandela himself, paying tribute to those actions and many others that were bringing inexorable pressure to the fight to end the inhumanity of apartheid.

“Thank you for supporting us when we needed you most,” Mandela told us that day. “Thank you for remembering us even though we were incarcerated in prison dungeons thousands of miles away from here. Thank you for caring. We are on freedom road, and nothing is going to stop us from reaching our destination.”

After the speeches, at a reception hosted by the mayor, I had a chance to shake Mandela’s hand and exchange a few words with him. There was so much I wanted to say about my admiration for him, but with the crush of people all around us, there was only time to exchange a few casual pleasantries. Still, it was an opportunity I treasure to this day.

Not just because it was a chance to meet a personal hero, someone I’d admired from afar since my own early days as a human rights activist. But also because of what he showed the world following his release after 27 long years in prison. It was inspiring and remarkable to me that when he came out, retribution was not on his agenda—reconciliation was. When he went on to lead South Africa as its president, he was inclusive. Healing his beloved country would take working together, and no one showed the power of a collaborative spirit more than Mandela.

He set an enduring example of cooperation and selflessness that’s not often seen in public life these days.

As Mandela was memorialized after his death last week at the age of 95 by leaders including President Barack Obama in Johannesburg, I found myself thinking about the power of individuals to change the world—the importance of taking a public stand against injustice, and of lending our vocal and moral support to those, like Mandela, who put their necks on the line for a cause greater than themselves.

Every generation has its heroes—those all-too-rare individuals who stand up and make a difference. In our times, they’ve included the late Andrei Sakharov, the “voice of conscience” against human rights abuses in the Soviet Union and the inspiring Aung San Suu Kyi in Burma. But no one, I would argue, had the impact and experience of Mandela, who paid such a profound price in terms of the years of solitary confinement, yet emerged from behind bars to see the comparatively swift demise of the apartheid system he fought so effectively against.

He stands alone. And those of us fortunate enough to have even once crossed his path will always stand in awe.

Posted 12/10/13

Remembering JFK

November 22, 2013

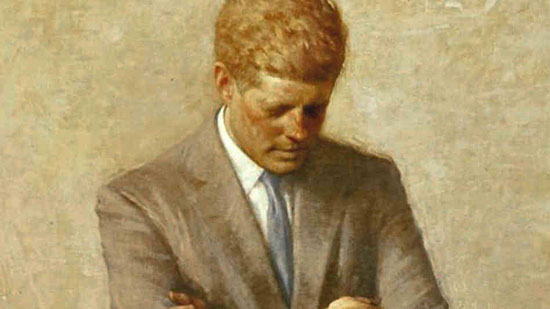

John F. Kennedy's official presidential portrait by artist Aaron Shikler was posthumously unveiled in 1970.

It was the fall of 1960, just two months before the presidential election, and John Kennedy was making a swing through Los Angeles for a rally at the Shrine Auditorium. I was 11, and I was determined to be there.

Kennedy already was my hero. When he challenged us with his youthful energy to give more of ourselves in the service of others, he sparked a political flame in me. So I begged my dad to take me to the Shrine. Before we jumped into our Plymouth for the drive downtown from our Fairfax home, I grabbed a stick in the backyard and taped a Kennedy bumper sticker to it.

When we arrived at the Shrine, the place was mobbed. We couldn’t get inside but, because I was small, we snaked and jostled our way through the thick forest of excited grown-ups to the very front of a walkway where Kennedy would pass to enter the auditorium. As my striding hero approached, I shouted and waved that stick so wildly that he had to step back to keep from getting whacked.

Inside the auditorium, the candidate would speak on the weighty matters of the day—the tightening tensions between democracy and communism, survival in a difficult and dangerous world, racial and religious bigotry. As I sit here now, I suspect most of those policy points would have gone over my head. But the promise of a New Frontier that Kennedy carried into L.A. and across the nation certainly didn’t miss the mark with my heart.

In recent days, we’ve seen stories of every sort and slant on Kennedy and his administration to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his assassination in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Scholarly debates over the impact of his presidency will persist for decades to come. So too, I imagine, will the lingering conspiracy theories that swirl around the rifle shots fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

But in my circle of friends, we’ve found ourselves talking less about the details and what-ifs of JFK’s presidency and more about his personal impact on the course of our lives during such formative ages. Truth is, many of us have never gotten over Kennedy’s death. It was so sudden, so personal. In that sense, it reminded me of the grief of my mom’s passing just four years earlier.

During Kennedy’s tenure, we were still too young to be skeptical or, worse, cynical from the experience of some earlier political disappointment. When John Kennedy said anything was possible, we believed. When he told us we could make a difference, we acted—even if it was in our own, youthful ways.

I can still remember running for Boy’s League vice president in 9th grade at Bancroft Jr. High School in Hollywood after Kennedy’s election—my first political race. During a campaign “speech” to the students, I informed them that a special guest was there to offer support for my candidacy. I turned around and pulled on a Kennedy mask that I’d been hiding behind my back. I then swung around again and, in what I’d like to think was a pretty spot-on Kennedy impersonation, urged the now-cheering students to cast a ballot for Zev. I won, with 90 percent of the vote.

Today, I look back at my silly play-acting and know, on a deeper level, that I was identifying for the first time with a real-life political figure, an identification that has inspired me throughout my nearly 40 years in elective office. The political activism to which I’ve dedicated my life began with Kennedy.

During the past few days, amid all the news coverage, I’ve been asked the difficult question of how I think the Kennedy assassination is relevant to today’s younger generation. Why should they care?

Many historians have asserted that the political and cultural upheaval of the 1960s—which informs much of who we are today—began on that sad day in Dallas. The president’s killing set the stage for the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., Bobby Kennedy and too many others, seemingly raising the nation’s tolerance for political violence.

But the reality is that for those of us of a certain age, our most visceral connection to the assassination is with the seared memories of where we were and how we felt when we heard the news. (I was in Spanish class, where my teacher dissolved into tears.) The gut-wrenching depth of that individual grief, multiplied by millions across a nation, can never truly be expressed to anyone who wasn’t there.

Maybe the most we can do to convey that trauma to the Millennial Generation is to note the impact the 9/11 attacks had on their lives. Ask any of them, and they can vividly tell you where they were when the towers of the World Trade Center came crashing down.

But, on a more positive note, I might also offer them a few words from the speech that candidate Kennedy delivered inside the Shrine Auditorium, as my dad and I worked our way back to the car—a reminder of the timeless relevance of his vision and of our responsibilities.

“If we measure up not only in the public sense,” Kennedy said, “but in the private sense to the opportunities that we have, if we recognize that…liberty calls for certain qualities of self-restraint and character which go with self-government, I am confident that the future can belong to those who believe in freedom.”

Posted 11/22/2013

A cop’s cop

October 31, 2013

Daniel Sullivan wore his LAPD blues like the rest of the command staff, but he was definitely cut from a different cloth.

In an era when then-Chief Daryl F. Gates set a combative tone for the department, Sullivan, a deputy chief, refused to succumb to such them-against-us nonsense. That was evident in the unlikely relationship he and I forged.

Not long after my election to the Los Angeles City Council in the mid-1970s, I became the panel’s strongest critic of the department’s use of excessive force and its propensity for secretly building dossiers on perceived enemies, including me. Although Sullivan didn’t always agree with me, he said he respected my willingness to tackle the brass. And I, in turn, told him I respected the professional manner with which he and most of his colleagues performed their crucial and difficult responsibilities on behalf of the residents of Los Angeles.

With his jurisdiction stretching across my Westside district, Sullivan would become one of my “go-to” guys when I needed thoughtful and blunt guidance on a criminal justice issue. I’d go on ride-alongs with him until the wee hours to get his unique take on the city he patrolled. Then we’d compete on the racket ball court. He had a boyish, Irish grin straight out of Central Casting.

Many years ago, Sullivan and an LAPD colleague, Joe De Ladurantey, published a book called “Criminal Investigation Standards.” To this day, that volume sits on my shelf—a continuing reminder that you don’t have to be in lock-step with a person to form lasting professional and personal ties, if the relationship is grounded in mutual good will.

As you may have suspected, I’m writing about Sullivan because I learned last week that he passed away.

The last time I talked to him was not long after the 9/11 attacks, years after his retirement. He called me from, of all places, Pakistan. He said he’d been hired by the U.S. government for a border security and police modernization project to help that nation secure its borders. Then I lost touch; I heard he moved to Palm Desert and was easing his way into retirement.

One of the LAPD’s brightest stars, Sullivan had the policing and political skills to become chief of police one day. Only a quirk of timing and the lack of a vacancy prevented that from happening during his years within the department. What a shame. He was the closest friend I had in the LAPD, and I will miss him and what our friendship represented.

Posted 10/31/13

A time to stay the course

September 19, 2013

After many years in office, I know how tempting it is for political bodies to jump into action when a problem is generating headlines or otherwise commanding public attention. But sometimes what sounds like a good idea may actually be counterproductive, falsely raising expectations at the precise moment when careful and dispassionate analysis should rule the day.

Such an issue surfaced this week at the Board of Supervisors, where my colleagues Mark Ridley-Thomas and Gloria Molina introduced a motion calling for the permanent creation of a Sheriff’s Department Oversight Commission, whose members would be appointed by the board.

They argued that ongoing investigations by the U.S. Justice Department and continuing allegations of brutality by deputies in the jails proved that a new level of civilian oversight was needed—one that a busy Board of Supervisors alone cannot provide. A vote is scheduled for October 8.

I certainly share the proponents’ desire to tighten the reins on the Sheriff’s Department, but let me tell you why I’ll be among the “no” votes.

As many of you may know, I’ve spent a good deal of my public life holding our region’s two biggest law enforcement agencies accountable for unconstitutional behavior, from the political spying and excessive force of the Los Angeles Police Department back in the 1980s to the escalating brutality inflicted on L.A. County jail inmates by sheriff’s deputies in more recent times. In fact, I championed the establishment of the Citizens Commission on Jail Violence, whose esteemed members last year proposed more than 60 reforms for the Sheriff’s Department’s jail operation.

The lynchpin of those widely-praised recommendations was the creation of an Office of Inspector General to provide rigorous, independent oversight of the department, reporting directly to the Board of Supervisors. We will soon review candidates to lead this essential watchdog agency.

The blue-ribbon panel—whose members included former federal judges, a big-city police chief and a prominent south Los Angeles pastor—specifically considered whether to recommend the creation of a permanent civilian commission, like the one now being proposed. The answer: no.

“The Commission believes that a fully empowered and integrated Office of Inspector General reporting to an engaged Board of Supervisors can provide the necessary independent oversight of the Department to ensure that it implements meaningful and lasting reforms,” the panelists wrote in their final report. The creation of another civilian commission, they said, “was not necessary.”

And should anyone question the Board of Supervisors’ level of engagement, Tuesday’s meeting alone should have offered an answer. Besides the proposal for a new oversight body, our day was packed with reports and debate on the status of the earlier jail commission’s recommendations, the decreasing number of serious use-of-force cases, and methods of coping with thousands of new inmates now serving sentences in the county lockup rather state prison because of sweeping changes to California law.

The strongest argument against a new oversight commission is simply that it would be powerless to force changes within the Sheriff’s Department. And, despite the suggestions of the measure’s backers, the Los Angeles Police Department does not provide us with a model for civilian governance.

The sheriff is publicly elected, making him directly accountable to voters every four years. Although the Board of Supervisors holds the purse strings, state law expressly gives the sheriff here and in counties across the state wide control over the operations of their departments. The LAPD chief, on the other hand, is politically-appointed and, under the city charter, reports directly to a five-member Board of Police Commissioners, which governs the department.

In their final report, the jail commission pointedly noted the difference between the two law enforcement agencies, saying that “a civilian jail commission would not have any legal authority over the Sheriff’s Department absent enabling [state] legislation.” The probability of getting such legislation is, at best, remote. In other words, the proposed commission would amount to little more than a soapbox for the panelists—and a disappointment for those of us committed to a top-to-bottom cultural change.

On Tuesday, my colleague, Don Knabe, called the proposal for a new commission “a bit premature.” I agree. The Citizens Commission on Jail Violence, staffed by some of L.A.’s brightest criminal justice minds, offered us a detailed roadmap to reform. That includes allowing an inspector general—whose authority Sheriff Lee Baca has said he will accept—to hold the department accountable through meaningful oversight.

We shouldn’t now be looking for shortcuts that, in the end, would divert us from our destination.

Posted 9/19/13

The next front in jail reform

September 12, 2013

The county is exploring a new stand-alone facility for the incarceration and treatment of mentally ill inmates.

It’s now been two full years since my colleagues on the Board of Supervisors and I appointed a special commission to investigate allegations of widespread brutality by deputies in our county jails. The panel’s creation stands as a clear demonstration of our commitment to ensuring that the constitutional rights of inmates are protected and that members of the Sheriff’s Department, no matter what their rank, are held accountable for transgressions.

Among its findings, released one year ago this month, the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence recommended dozens of reforms to restore integrity to the nation’s largest jail system. Although some of those reforms have yet to be implemented—including the hiring of a watchdog Inspector General—measurable improvements are taking root.

But the job’s not nearly done. This is especially true when it comes to a big slice of the jail population that poses a uniquely difficult challenge for the county—the more than 2,000 inmates coping with mental health issues. In an environment of control and conformity, they require a level of individualized care that the system seems unable to consistently provide.

The Sheriff’s Department certainly didn’t ask for its jails to be our mental hospitals of last resort when state mental health dollars and facilities began disappearing decades ago. Clearly, the county’s far-flung lockups were neither designed nor intended for the special needs of these troubled individuals whose mental state likely contributed to the criminality that led to their confinement. But that’s the reality we have faced for years, and it is our obligation to act now with the same sense of urgency we’ve displayed in confronting the problem of deputy violence.

In fact, we’ve been assuring the federal government of our dedication to this mission for the past 11 years, assurances that now apparently have worn thin.

In 2002, the county entered into a Memorandum of Agreement with the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, which had concluded that the jail’s staff was engaged in such “abuse and mistreatment of prisoners with mental illnesses” as improperly using physical restraints and providing inadequate facilities and staffing. The Sheriff’s Department, along with the county’s mental health agency, agreed to fix the failings and cooperate in bi-annual federal inspections to ensure that inmates’ constitutional rights were not being violated.

But last week, U.S. Justice Department officials notified the county that they were opening a civil investigation into the allegations of excessive force and undertaking a new “assessment” of the mental health agreement. In a letter to Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka and Sheriff Baca, justice officials acknowledged the county’s progress in this latter area, but stated bluntly that “significant problems remain.” They cited, among other things, the growing number of inmates with serious mental illnesses who are being housed in “obsolete and dilapidated conditions at Men’s Central Jail” and an increase this year in jail suicides.

I fully agree that the current conditions for mentally ill inmates inside the archaic and depressing central jail are unacceptable—as do my colleagues. In May, acting on a motion I authored, the board voted to take the first steps in the possible construction of an Integrated Treatment Center, which would house all mentally ill inmates and provide care consistent with the federal Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act.

Our action, which represents a potential investment in jail reform for the mentally ill of well over $1 billion, should clearly signal to federal officials our desire to get this right.

I know there are some who’ll see the federal government’s stepped-up scrutiny of our jail system as an intrusion into our local affairs, usurping our sounder, closer-to-the-ground judgment. I disagree. I believe the federal government’s concerns will generate an important public conversation about what needs to be done so the county can move forward without potential federal litigation to force our compliance.

And that conversation could not come at a more crucial time, as our bursting jail system confronts unprecedented pressures because of state legislation AB 109, which has crammed thousands of new inmates into county cells, inmates whose crimes used to land them in state prison.

I also know that the mental health challenges of our inmates do not generate a great deal of concern among a general public that is more concerned about the safety of their neighborhoods. But these are not mutually exclusive goals. Studies show that recidivism drops among mentally ill/dually-diagnosed inmates who receive intensive treatment.

Our system of constitutional government requires that we humanely treat those we place behind bars. But providing adequate mental health treatment to the thousands of inmates in our county jail should also be embraced as a matter of enlightened self-interest.

Posted 9/12/13

A breakthrough for vets

August 2, 2013

A few years ago, I was participating in the county’s biannual homeless census when I came upon a man sleeping under a bush on La Brea Avenue. It was winter, about 4 a.m. The man had been on the streets for ages. He shivered awake, and we talked for a few minutes, his breath steaming the night air, his clothing disheveled. Among other things, he told me he was a veteran.

That conversation was as heartbreaking as it was emblematic. More than 6,000 of Los Angeles County’s homeless are former military servicewomen and servicemen. Once, they volunteered to give their lives for their country. Now they wander our streets, their minds and bodies often addicted or damaged, their chances higher than average of ending up in the ranks of long-term street people at massive public expense.

That’s why, two years ago, we partnered with the Department of Veterans Affairs to launch a pilot program, a spinoff of our successful Project 50, to provide permanent supportive housing for a group of veterans identified as most likely to die on the streets.

There were 60 to start, severely mentally ill and chronically homeless. And, as with Project 50 on Skid Row, our veterans initiative, dubbed Project 60, started with the premise that if you give someone housing first—no moralizing, no demanding that they get a job or sober up as a condition of shelter—they’ll be more amenable to any medical, mental health or substance abuse treatment services you offer. That, in turn, will spare taxpayers the much higher cost of housing them in hospitals and jails.

It was a novel idea, and today, I am thrilled to report that it has paid off.

This week, during a meeting in Washington, D.C., with U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, Rep. Henry Waxman and myself, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki committed to dramatically scaling up the program, which, according to this year’s homeless census, contributed to a stunning 23% drop in the number of homeless vets over the last two years in Greater Los Angeles.

The VA’s commitment—part of the Secretary’s long-stated goal of ending homelessness among veterans by 2015—will fund and support a sweeping expansion of homeless services for veterans in L.A. County, from housing vouchers to medical outreach to a dedicated homeless services center at the West Los Angeles VA facility.

In all, it will allow us to house and treat more than ten times as many homeless vets in the next two years as we did over the last two. During this period, we expect to house 1,320 chronically homeless veterans. This represents the single most significant development on this issue in years.

It’s also the result of a lot of hard work and collaboration by Sen. Feinstein, Rep. Waxman and staff including Donna Beiter, who directs the VA’s Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, the VA’s Michelle Wildy, Flora Gil Krisiloff in my office, Mary Marx with our county Department of Mental Health and front-line nonprofits Ocean Park Community Center in Santa Monica, St. Joseph Center in Venice, San Fernando Valley Mental Health Center and the Hollywood branch of Step Up on Second.

And it’s proof that when we build on our successful programs, we can make a life-saving difference. We have helped nearly 120 homeless mentally ill veterans through our original Project 60: a sailor who spent the past 15 years sleeping in a Santa Monica park and making monthly emergency room visits until he got housing; a former Marine who, after a decade, has begun to get sober in her Gardena apartment; a Vietnam vet, dying of cancer in a hospice, who came in from the night in time to make peace with his anguished family. Now the number being cared for will dramatically increase.

These veterans answered the call of our country when we needed them. Now they need us, and this week marks a huge breakthrough in helping Los Angeles answer that call.

Posted 8/3/13

A new river runs through it

July 25, 2013

For most longtime Angelenos, the Los Angeles River has represented little more than a concrete scar across the county, a channel sending urban runoff and debris towards the sea. Although largely justified in the past, that perception has failed to keep pace with the river’s emerging new realities and its potential to become one of the grandest urban greenways in America.

There was a time when the Los Angeles River was a lifeline for our region. Along its banks, the Gabrielino Indians hunted, fished and lived. The Spanish established the city’s earliest settlements on the river, which would later power the area’s industrial growth. But by the early 20th Century, the river simply could no longer co-exist with the Los Angeles Basin’s explosive growth. A deadly flood in the winter of 1938 finally led to its encasement in concrete, paving the way for the river to become more famous as a backdrop for movie car chases than for its real-life story.

To be sure, long stretches of the river’s 51-miles remain as barren today as they did a quarter-century ago. But elsewhere, a rebirth has been taking root like the lush foliage that again blankets the riverbed between downtown L.A. and Griffith Park. In fact, through a burgeoning public-private partnership, a reimagining of the river’s place in modern-day Los Angeles is gaining unprecedented traction.

President Obama recently made the rejuvenation of the L.A. River a top priority in his urban waterways initiative. And with the federal government’s earlier recognition that the river should be open for recreational use, higher water quality standards are also on the way.

The City of Los Angeles, along with the county and other municipalities, has built miles of new bikeways along the river. In April, NBCUniversal committed nearly $14 million toward the completion of a 6.4 mile gap between Griffith Park and Studio City. Pocket parks also are sprouting on the river’s banks. A summer pilot program has people from across the region kayaking and fishing in its Glendale Narrows passage. And this week, we celebrated the public and private support that will soon give rise to La Kretz Crossing—a stunning pedestrian, equestrian and cyclist bridge near Atwater Village.

But all this is only a start in turning the river into a truly vibrant public space, where our diverse population can not only share recreational opportunities but also forge a broader sense of community from the valley to the ocean. In one of the nation’s most densely developed regions, the Los Angeles River represents a unique opportunity to transform blighted infrastructure into a scenic refuge—a quintessentially L.A. version of New York’s hugely popular “High Line,” a mile-long aerial park built along old railroad tracks.

That’s the charge of Greenway 2020, an initiative spearheaded by the non-profit Los Angeles River Revitalization Corporation, which has an immediate goal of completing all 51 miles of the river bikeway by the end of this decade. Filling in gaps totaling 24 miles through government and private financing, the path would extend from the west San Fernando Valley to Long Beach, complete with amenities such as bike shops, eateries and picnic sites.

Daily commuters would be able to ditch crowded roads and buses in favor of a beautiful—and healthy—bike to work. The 100,000-plus cyclists who’ve turned out for the street-closing CicLAvia events is proof of the pent-up demand for bicycle experiences that don’t compete with automobiles. Entire families, meanwhile, would have a desperately needed getaway in our concrete landscape to play, to breathe and to build memories.

Every world-class city has public spaces that define it. But these monuments to urban life don’t build themselves. Communities come together to create them, and such will be the case for Greenway 2020. It will require coordination and commitment among L.A.’s community leaders, its governmental agencies and its private sector, including business and property owners along the river.

Most of all, it will require a grassroots movement to prove that Los Angeles is ready to make this vision a reality. We urge you to get involved – sign up at larivercorp.com to join Greenway 2020’s effortsand learn more about the project. Attend community meetings. Convey your support to your elected officials. Participate in L.A. River cleanups. Bike and kayak with your friends.

And help us chart a course for the river that will, once again, let it nourish life across Los Angeles.

This piece was co-authored by Allan J. Abshez, board member of the Los Angeles River Revitilizaton Corp.

Posted 7/25/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information