New beach chief rides the waves

Gary Jones’ new job as director of the Los Angeles Department of Beaches and Harbors is a little like going surfing while wearing a tie. It’s an ongoing attempt to marry L.A.’s freewheeling beach culture with business concerns such as permits, parking, environmental impact and—always—budget.

Access to L.A. County’s beaches remains an emotional issue for residents, many of whom treasure days at a local beach among childhood memories, Jones says. The 45-year-old Englishman’s first visit to Southern California took him to Venice’s Muscle Beach. “Venice Beach and the L.A. lifeguards are iconic, in part from Baywatch. Surfing, the beach life, the fire pits —that type of culture is very much transmitted around the world,” Jones says.

Jones’ Marina del Rey office affords a picture-postcard view of blue sky, seagulls and sailboats. Hailing from the English “rowing town” of Bedford, he loves to observe rowing teams from UCLA and Loyola Marymount University take on the chilly early mornings. On his desk are the less enticing realities of the gig: The first proposed increases in fees affecting the public since 2009 are set to come before the Board of Supervisors next week. They include increases in summer parking fees, beach permits for organized recreational classes such as yoga, youth camp expenses and dry storage of trailered boats.

And if past experience is any guide, those kinds of changes—ranging from new meet-up rules to a misunderstood Frisbee policy—can kick up a lot of sand.

“In the dynamics surrounding the county’s operation and ownership of beaches and the coastline, there are some very interesting forces at play,” adds Jones, who served as interim director for eight months before stepping into the permanent post on April 15. “Underpinning it all is that overwhelming sense that this is something the public should have access to. Some people think that access translates to free, or as low cost as possible. Or if I want to join 50 or 100 of my closest friends and train for a triathlon, I can do that.”

Standing out among the currently proposed increases are a new fee for the annual senior parking pass ($25) and substantial hikes for five-day youth camps, some of which have recently been on hiatus. Sailing and surf camp fees would go up sharply (sailing rising from $165 per participant to $375, surf camp from $165 to $300). Jones notes that the department continues to look for ways to cut operating costs so fees may end up being lower than proposed. He adds the department will still give financial assistance to needy participants.

Jones says the department is also looking to expand the county’s popular water taxi service that transports the public to concerts and events at Chace Park, along with other stops including Fisherman’s Village and Mother’s Beach. This summer, the service is slated to begin June 19.

Jones, who moved to the U.S. in 1998, began his Southern California career managing assets for the city of San Diego. He came to Los Angeles County’s beaches and harbors department in 2009. Jones stepped into the interim director position when then-director Santos Kreimann became acting county assessor after the elected assessor, John Noguez, was placed on leave pending a trial on corruption charges.

With the approach of Memorial Day and the traditional opening of summer beach season, Jones says his foremost concerns include the continuing redevelopment of Marina del Rey (money from private development flows into the general fund, he says) and beach maintenance for the summer onslaught (sand grooming, restroom upgrades, parking lot re-surfacing).

Also at the top of the list: A greater social media presence and a more user-friendly website to provide up-to-the-minute information on parking and rates, easily accessible by smart phone or tablet.

Jones adds that some beaches require a delicate balance between humans and wildlife. Visitors don’t always understand the needs of the grunion or the Snowy Plover, or why the “rack line” of seaweed left behind by the tide represents an important ecosystem, not just a source of odor and pesky sand flies. “We have 50 million plus people using our beaches every year —how do you balance that with being a good environmental steward?” muses Jones.

And why did Jones take on this balancing act? “No municipal department has the blend of what this department is responsible for,” Jones asserts.

“I don’t think I could have been satisfied churning out commercial real estate deals or office deals,” he says. “It’s very rewarding when you see a project come together and you see people enjoying it, the impact it has on a community. I think that’s what makes me tick.”

Posted 5/7/14

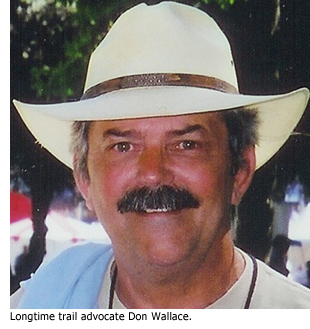

March was a banner month for Don Wallace. And not just because he and his wife, Jeanne, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

March was a banner month for Don Wallace. And not just because he and his wife, Jeanne, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

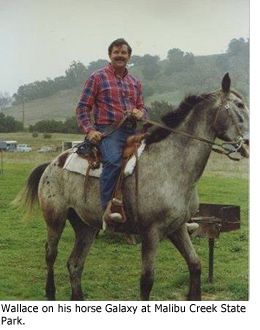

The couple settled in Canoga Park , had two sons and got into horseback riding, eventually deciding that they wanted enough land to have their own corral. Wallace, by now a Los Angeles city firefighter, found a spread near the unincorporated community of Monte Nido, and the couple built a house on it. They still live there with assorted horses, cats and dogs and a potbellied pig.

The couple settled in Canoga Park , had two sons and got into horseback riding, eventually deciding that they wanted enough land to have their own corral. Wallace, by now a Los Angeles city firefighter, found a spread near the unincorporated community of Monte Nido, and the couple built a house on it. They still live there with assorted horses, cats and dogs and a potbellied pig.

“Continuing the work on this project is important to helping restore degraded habitat along the channel, providing nesting opportunities for migratory birds and establishing a corridor for wildlife movements,” said Col. Thomas H. Magness IV, commander of the corps’ Los Angeles District.

“Continuing the work on this project is important to helping restore degraded habitat along the channel, providing nesting opportunities for migratory birds and establishing a corridor for wildlife movements,” said Col. Thomas H. Magness IV, commander of the corps’ Los Angeles District.