Coasts & Mountains

Charting a sea change

March 20, 2014

Hotter heat waves in the Valley. Smaller snowcaps in the mountains. Worse flooding during storms on Pacific Coast Highway. Study by study, local scientists are gradually pinpointing the ways in which climate change could impact Southern California. The news has been sobering.

Now, the county is preparing to zoom in on another piece of the picture, with a look at rising sea levels at the 21 beaches it operates and maintains. Approved this week by the Board of Supervisors and funded in large part by a grant from the California Coastal Conservancy to the county Department of Beaches and Harbors, the $86,815 study will run from April to October, and add to a growing body of work on the local impact of climate change.

“There have been broad projections about what sea level rise might look like, but that picture isn’t specific enough for what planners and policy makers need,” says Megan Herzog, a fellow at the UCLA law school’s Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment.

Although the City of Los Angeles has made some headway, most notably with a recent study on the potential impact of sea-level changes along the city’s coastline, “most local governments are just at the data gathering stages,” says Herzog. “So we’re really just at the beginning of thinking about impacts and making plans.”

With more than 52 million visitors a year just at the beaches that are county-owned or -managed, a full assessment of the coastline’s vulnerability is critical both to the environment and to the economy, says Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director at Beaches and Harbors.

“One study found that sea levels on the West Coast have risen twice as fast over the last five years as they did over the last twenty,” says Silverstrom, noting that the sea level is projected to rise by up to two feet by 2050. “So we need to look at what are we going to do as operators of the beaches to protect them?” she says.

Higher tides not only can flood low-lying buildings and roads, but can also exacerbate storm damage by undermining parking lots and damaging coastal sewer lines. These issues are of particular importance on the county-maintained and operated beaches, which range from Royal Palms in the South Bay to Malibu’s Nicholas Canyon, and include such landmarks as Marina Del Rey, Point Dume and Venice Beach.

The city’s January sea level study, done in cooperation with USC, found that the Port of L.A. and energy facilities along the coast were in good shape to withstand the impact of rising sea levels. However, low-lying communities such as Wilmington, San Pedro and Venice are especially vulnerable, as is Pacific Coast Highway, which already floods regularly in some places when winter storms hit.

The study found that even a moderate storm could do more than $400 million in damage on the city’s share of the beaches if the sea level were to rise here by just 18 inches or so, a mark that easily could be reached by 2050. Also at risk are wastewater and drinking water systems near the high tide line.

Charlotte Miyamoto, head of the planning division at Beaches and Harbors, says the county’s research will have big implications for county public works projects such as sea walls and sand berms—protective structures that the county uses to prevent crashing waves from scouring beaches, undermining parking lots and flooding Pacific Coast Highway.

Although critical in mitigating the ocean’s impact on infrastructure on which the public relies, residents in Venice and Marina Del Rey have complained that the temporary berms, in particular, block their view of the ocean—a complaint that seems likely to be amplified as rising sea levels raise the risk of damage from storm surges.

“How big and wide will we need to make those berms?” says Miyamoto. “Will we want to build structures in the water to deal with erosion? The beaches are our first line of defense as the sea level rises,” says Miyamoto, “and so we want to make sure they’re preserved.”

More broadly, the county study also will help focus policy choices, says Herzog. Already, she noted, coastal cities elsewhere in California are moving bike paths and other amenities away from narrowing beaches and rising tides.

“This region is really densely developed along the coast,” she says. “In some cases, we have development right up along the backs of beaches, and that’s going to mean we have to think about priorities. We have to decide if it’s important to preserve beaches and wetlands and ecosystems, for instance. And if it is, then it’s going to mean tough decisions about development up and down the coast, and it could mean major changes in land policy over the long term. Because something has to move.”

Silverstrom noted that the Beaches and Harbors study, while narrow, is just one part of a broad effort the county has been undertaking for the past two years to prepare for climate change. A series of climate change studies led by the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability has projected, among other things, that average annual temperatures in Greater L.A. will rise by an average of 4 or 5 degrees by 2050, that days of extreme heat will quintuple in inland areas and the valley and that the area’s mountains will get about a third less snowfall.

So, acting on a 2012 motion by Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael Antonovich, county departments across the board have been assessing the potential impact of climate change and trying to mitigate its potential costs.

The county Fire Department, for instance, has revised training protocols to account for the warming climate. The Internal Services Department has been working to reduce the carbon footprint at county buildings and to improve energy efficiency. The Department of Public Works, meanwhile, has been trying to capture more storm water, and to replace gas-fueled trucks with more eco-friendly vehicles.

Silverstrom of Beaches and Harbors says the latest study will help pave the way for short, medium, and long-term solutions to rising sea levels, coastal erosion and more powerful storms in the future.

“This is about resilience,” she says, “about how we can sustain our beaches for the public while recognizing what’s happening in the environment.”

Drought reigns in plant kingdom

February 6, 2014

A volunteer helps plant one of 24,000 seedlings that have languished in a nursery because of drought conditions on hillsides charred by last year's massive Springs Fire. Photo/Steve Friedman

Last spring, after Sycamore Canyon was devastated by the earliest fire season in memory, Irina Irvine raced to protect the scenic landmark from an ancillary threat.

A restoration ecologist with the National Park Service, Irvine had been working to rid the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area of destructive non-native grasses. Some of her most successful work had been in the hills around Newbury Park, where, in May, the fire had started.

Knowing that opportunistic plants could retake and wreck the natural ecosystem if she didn’t act quickly, Irvine prepared 24,000 native seedlings—elderberry and oak, coastal sage and purple needle grasses. Then she waited for the winter rains, when the sprouts could be planted.

And waited. And waited.

“Twenty-four thousand plants at $3 a plant, and several interns hired especially for this,” says Irvine. “And it hasn’t rained yet.”

Lawns aren’t the only landscapes that are starting to feel the effects of this year’s extreme drought. From street medians to coastal canyons, local naturalists say the shortage of water is having all sorts of unprecedented impacts.

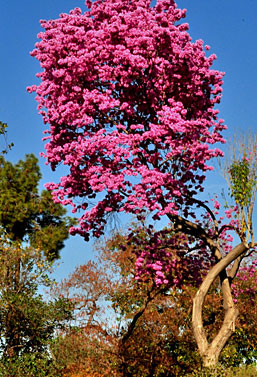

At the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, the absence of soil-cooling rain has tricked spring-blooming trees into blossoming as if it were April. In the San Fernando Valley, meanwhile, wildflowers are failing to germinate for lack of water.

In the Angeles National Forest, the drought has not only dried up natural springs but also emptied rain-catching “guzzlers”, small man-made reservoirs that provided a reliable fallback in past years for thirsty birds and wildlife. In the Santa Monica Mountains, the extreme water shortage has made historic oaks vulnerable to bark beetles and weakened even resilient trees such as eucalyptus.

“There’s been a lot of die-off in the native vegetation,” says Florence Nishida, a resident of Topanga Canyon and master gardener at the Museum of Natural History. “Landscaping at least has some source of water. But in the natural areas, the plants have gone since last March or April until now with hardly a drop of rain.”

Frank McDonough, botanical information consultant at the Arboretum, says the region is feeling a triple whammy—a years-long drought combined with a warmer-than-usual fall and winter and a high-pressure ridge that has cut off California’s usual dose of rain. Without a series of good, soaking downpours to cool down the soil, he says, the tree roots don’t realize it’s winter, and that, plus last month’s record heat, has left plants confused.

“Now our pink trumpet trees, which usually don’t bloom until March, are covered in blossoms, and the flowering apricots and nectarines are starting to bloom,” says McDonough, adding that more than a year or two of such unusual conditions can weaken trees and leave them vulnerable to disease and insects. Although it’s not necessarily good news, he says, “I expect the cherries will bloom earlier than normal, too.”

In wildflower country, on the other hand, the lack of rain is just depressing.

“It’s been pretty pitiful for the past two years, and it will probably be the same or worse this year,” says Lili Singer, director of special projects and adult education at the Theodore Payne Foundation, a Sun Valley nonprofit that operates an annual wildflower hotline.

For a good show, she says, wildflowers need at least one serious rain per month, starting in the autumn, so that they can establish themselves and produce plenty of buds before they start flowering. But with the exception of man-made seed-sowing initiatives such as Wildflowering L.A.—whose gardeners have been forced to water their supposedly drought-tolerant seedlings far more than expected—and the possibility that a few rare species will sprout in the wake of recent brush fires, Singer and other naturalists say they don’t have high hopes for this season.

“There’ll always be something for people to see,” says Singer, “but it will be a lot lower in the number of plants and the diversity.”

Nor are the wildflowers the only living things that are thirsty. In the Angeles National Forest, for instance, the county this week approved a grant to repair watering stations for wildlife and birds.

“This drought has just been real tough,” says John Forgy of the San Gabriel Valley chapter of Quail Forever, an organization that has offered to make the repairs as part of its work supporting wildlife. “And some of the young birds only eat insects, and there are no insects if there’s no rain.”

Irvine of the National Park Service says she has seen all these drought symptoms and more in the Santa Monica Mountains, where, in the plant world at least, “everything’s a little wacky right now.”

Vegetation, she notes, is vital in wildlands, not only because it’s habitat for wildlife, but also because it prevents erosion and counteracts global warming by sequestering carbon dioxide.

In areas like the mountains, where many species have evolved around drought, a dry year or two isn’t necessarily alarming.

“But you can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” says Irvine. “When I see a big eucalyptus that’s been here for 50 years dying because there’s no water, that catches my attention. Pine trees are being hammered. And we are already seeing significant die-back in chaparral communities, and we don’t know if they’ll pop back up again if it rains, or if, when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Particularly unnerving has been the effort to restore those 10 acres near the Wendy Trail head near Newbury Park at Rancho Sierra Vista in an area that was consumed last May during the freakishly early Springs Fire. Fueled by Santa Ana winds that had sucked the humidity in the air down to the single digits, the blaze swept from the canyons to the surf, consuming some 24,000 acres of drought-dried Los Angeles and Ventura Counties.

Among the casualties were some of the most scenic spots in the Santa Monica Mountains, including acreage on which Irvine had spent months trying to eradicate a particularly toxic and invasive strain of Australian bunch grass. The plan was to replant the area as quickly as possible with native seedlings that Irvine had carefully sprouted and set aside in a nursery.

“Normally what one does is wait for the first soaking rain of the year and then run, quick like a bunny, to get the plants in the ground as soon as the soil softens,” says Irvine. She had banked on an autumn planting. “But then when it didn’t rain in October, we were, like, ‘Darn it’,” she says. “And then no rain again in November. Darn it. And then December. And it was, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

The longer they waited, she says, the harder the earth got, making it even more difficult to transplant the seedlings that were in the nursery. And letting 24,000 seedlings die at $3 per seedling was not in the plan.

So when January came with no rain, she says, “We just said, ‘That’s it—we’re planting.’” Since January 17, Irvine says, she and a crew of interns and volunteers have been struggling to get the groundcover into the earth, which is so hard and dry that they’ve had to drill holes for the plants with a motorized augur.

“That’s 24,000 holes,” she says. “It’s been very slow going. We’ve only gotten about 9,500 plants into the ground, and we’ve been out there every day but Sunday and Martin Luther King Day.” Most recently, she says, she set aside $10,000 so she could water the plantings if necessary with a fire hose and a water tanker.

“If it rains substantially, of course, all bets are off,” Irvine says. “But from what I understand, just to get back to normal we’d have to have a couple of inches a day from now until about May.”

"You can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” Irina Irvine says of the drought. Seen here in green, she gets the troops ready for planting seedlngs in the hard dirt. Photo/Steve Friedman

Posted 2/6/14

The state of the shark

January 29, 2014

Last July at the end of a long beach day, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s helicopter spotted a 6-foot-long great white shark off of El Porto Beach. The copter’s loudspeaker was so clear that some South Bay locals heard it at home in their kitchens: Exit the water immediately.

To authorities in the air, it made perfect sense to issue a warning. Down on the sand, however, the sighting was familiar to county lifeguards—a baby great white feeding on small fish and stingrays, off the coast of a county that hasn’t seen even a hint of shark trouble in 25 years.

More broadly, however, the incident underscored the recent rise in local shark encounters, and the lack of a clear, uniform local policy on how to handle them. That’s why the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s Lifeguard Division will be hosting a symposium at Dockweiler Beach on Friday for local public safety personnel, elected officials and researchers. Organizers say the event is intended partly to work toward a policy consensus and partly as an opportunity to examine the state of the great white shark on beaches here.

“To my knowledge, no one has ever been fatally bitten by a great white in Los Angeles County,” says Chris Lowe, a marine biologist who leads the Shark Lab research center at Cal State Long Beach. (A suspected 1989 attack off the coast of Malibu was handled by Ventura County and never confirmed.)

“But the sightings have gone up, and the numbers seem to be going up, too,” Lowe says. “So this is partly to bring water safety people up to speed.”

Great whites are the best known of about ten shark species that can be found off the Southern California coastline, Lowe says, but they generally prefer habitats that are rockier and colder. Female sharks are believed to migrate to this area to give birth to their offspring, which may be why the sharks that seasonally show up in our waters tend to be juveniles under 12 feet, Lowe says.

Because great whites are hard to tag, he says, their numbers are hard to pin down.

“But their populations do seem to be increasing,” he says. Theories range from cleaner water and recovering fisheries to the fact that, as a candidate species under the state Endangered Species Act, great whites are protected in California, so it is illegal to catch and kill them.

That, however, hasn’t kept thrill-seekers and shutterbugs from seeking them out in numbers sufficient to prompt another theory—that there aren’t necessarily more great whites in the water, just more cameras.

Last year, a bumper crop of SoCal shark encounters showed up on YouTube, from a viral helmet-cam clip of a young great white swimming under an audibly nervous paddleboarder to footage of a surf fisherman reeling in a 3-year-old great white near San Onofre.

“You have to be prudent,” Lowe says. “Even though most of those sharks off Manhattan Beach were babies, if someone chases and corners them, they’ll do what any animal would if it feels threatened—it will attack you. It’s generally not a good idea to chase a shark around.”

Though the few shark attacks that have occurred south of Point Conception have been in other counties, Lowe says that he can understand the desire for local consensus on policy.

“In Hawaii, for instance, we trained lifeguards and helped them develop procedures based on things like the size of the shark, whether it appears to be aggressive and whether there have been indications that people or animals have actually been bitten,” he says.

“So at this symposium, we’ll be talking about what can be done, whether to close the beaches or post notices or just pass the word to other lifeguards. And some areas may already have some of those policies in place.”

Dan Murphy, ocean lifeguard specialist for the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s Lifeguard Division, notes that local beaches fall into a variety of jurisdictions. Most are guarded by the county, but some have state or local personnel guarding the waves.

In years past, lifeguards say, the lack of a single local policy on great whites hasn’t mattered much because so few attacks happened. Baby great whites, they say, have been known to cruise right under a surfer and pose no danger.

“But that’s not to say that one of those might not take a left turn one day and chomp a stand-up paddler,” says Lifeguard Capt. Kyle Daniels, who notes that San Diego has a well-developed response policy for shark sightings. “Outside Santa Monica Bay, I’ve seen sharks eating sea lions—not at highly populated beaches, but still.”

Tom Ford, director of marine programs at the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission, says it is important for coastal stakeholders to educate each other as they learn more about co-existing with an important predator.

“This isn’t some scene out of ‘Jaws,’ ” he said. “These animals are part of a healthy environment and we want them to go through the course of their day without any harm to their natural movement.”

Posted 1/15/14

Surf’s up—and rescues, too

January 29, 2014

Bone-crushing waves in Palos Verdes. Lookie-loos being washed off the rocks in Abalone Cove. Kids getting caught two and three at a time in rip tides.

It’s been a gnarly winter on Southern California’s coastline so far.

Faced with a triple threat of unusually warm weather, long holiday weekends and, most recently, high surf advisories, Los Angeles County lifeguards have been hustling to keep up with a decidedly unseasonal spike in attendance at the beach.

“I’ve been a lifeguard since 1986,” marvels Los Angeles County Lifeguard Capt. Tim Arnold, “and this is by far the busiest December and January I’ve had in my career.”

January attendance at county beaches is almost twice what it was last year, with nearly triple the number of rescues, lifeguard figures show. Spurred by heat waves that have sent temperatures into the 90s in some parts of Southern California, beach-goers have hit the sand more than 2.6 million times this month, and lifeguards have had to make more than 111 rescues.

That’s not counting the thousands of people who have had to be warned away from dangerous water, or the hundreds who have gotten into enough trouble to require medical attention. And January isn’t over yet.

“This year’s Martin Luther King holiday was probably the biggest winter day I’ve ever seen in my life,” says Arnold. “Between Manhattan Beach and Hermosa Beach, we had, like, 20 rescues.”

Complicating the job has been a swell produced by a storm system over the central Pacific that has been generating 10- and 12-foot waves along parts of coastal Southern California. South Bay beaches have been hardest hit, but county lifeguards also have felt it in Santa Monica and Malibu.

“It’s been tough for the guys sitting on the towers,” says Lifeguard Capt. Tim McNulty, who works the beaches from Big Rock in Malibu to Nicholas Canyon. At Zuma Beach, he said, only five of eight stations could be manned on MLK weekend because so many people on the “recurrent” list of part-time seasonal lifeguards were away at winter jobs or college.

“Everyone was on the edge of their seat with this surf and all those people,” says McNulty. “And we had hired everyone who was available on the recurrent list. We were calling people out of the blue.”

Lifeguards say rescues have been routine in nature, but summer-like in volume, with an inordinate number of novice surfers in over their heads.

“A lot of them are people on these boards called Wavestorms, that they sell at Costco for like $100,” says Arnold. “They’re like soft surfboards, and they essentially put a board into the hands of anyone who wants one, and these people are coming down and getting caught in situations they shouldn’t get caught in.”

Lifeguard Capt. Chris Linkletter, who also works in the South Bay, says daredevils and curiosity seekers have also been a problem.

“We had a surfer who broke his leg at the bottom of the Palos Verdes cliffs this week, and two people who were washed off the rocks in Abalone Cove,” she says. “We had some ‘blitzes’, too, where two or more people have to be rescued, usually from rip currents. Everybody’s seeing the high surf advisory on the Weather Channel and we’re having a lot more people who want to come out and take a look.”

Linkletter says she’s been advising all who will listen to remember a few basic safety tips for visiting the beach.

“Don’t swim alone,” she says. “Stay near an open lifeguard station. Keep a safe distance from piers and rocks, and obey the signs and warnings. And always check with the lifeguard to make sure conditions are safe.”

Lifeguards say they’re hoping for some relief this weekend, when Super Bowl parties are likely to keep at least some people at home.

“Other than that, I’m just waiting for rain,” says Arnold. “Though we don’t seem to get any of that anymore.”

Posted 1/29/14

A safer shortcut

September 5, 2013

A winding bike path has some cyclists opting instead for the access road, shown in foreground above.

For years, cyclists have been streaking along a service road through Dockweiler Beach in Playa del Rey to avoid a crowded, winding, sandy stretch of the bike path just a few hundred feet away. But the popular alternate route has created safety headaches of its own when the bikes cut through an RV park to get back to the path.

“On occasion, bicyclists have been struck by motorists,” said John Burton, a civil engineer for Los Angeles County Department of Public Works. “Luckily, vehicles aren’t going too fast there.”

The county’s Department of Beaches and Harbors manages the RV lot, one of four connecting with the 1.4-mile access road. Carol Baker, a spokeswoman for the agency, said employees have long supported a separate path between the road and the beachfront Marvin Braude Bike Trail, which snakes 22 miles up the coast, through major tourist destinations like Venice and Santa Monica. Cyclists cause damage when they hit a vehicle gate arm at the lot entrance, she said, and RV tenants have voiced concerns about the large amount of two-wheeled traffic.

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors authorized the Department of Public Works to proceed with a grant application to fund a new 385-foot connector path so cyclists won’t have to cut through the lot. Burton, who is planning the project, said the new path will create a better environment for campers and cyclists alike.

“With this path they can enter the bike path promptly and safely,” said Burton. “Right now they have signs to discourage people from going through, but people still do because it’s the easy way to go.”

Just last winter, the county renovated part of the path to repair cracked segments. However, Eric Bruins, planning and policy director for the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition, said the real problem is the path’s layout and design.

“It’s kind of a mess right now,” he said. “There’s a lot of sand on the path sometimes, so it’s pretty dangerous at times.”

That’s prompted many riders to turn to the access road as a straight-ahead, faster moving alternate to the winding beach route, Bruins said.

Another issue arises when large numbers of pedestrians wander onto the path at popular beaches. Beachgoers “are there to have a good time,” Bruins said, “but they aren’t exactly paying attention.” He said extra signage and path striping in places like Santa Monica have helped prevent people from crossing unsafely.

Despite the bumps and bruises, the trail remains highly popular among residents and tourists.

“You don’t have that kind of uninterrupted bikeway except by the rivers inland,” Bruins said. “It is a world class amenity—one of the must-do things when you visit L.A.”

Posted 9/5/13

When nine lives aren’t enough

June 20, 2013

Wildlife biologist Joanne Moriarty says fire adds yet another dimension to the stresses on the region's bobcats.

The sighting was unusual and upsetting. Just days after fire-ravaged Sycamore Canyon re-opened, worried hikers began to report seeing a bobcat sitting passively on a charred trail. Alarmingly skinny, she was not running away. Her whiskers were singed, and it was clear she’d had an earlier encounter with people. Her ears, they said, were tagged.

National Park Service officials, who’ve been tracking and studying bobcats in the Santa Monica Mountains for years, searched the canyon but couldn’t find the spotted cat. Then, earlier this month, a report came that left no uncertainty about the animal’s condition or location. A hiker found her dead a few miles beyond the Point Mugu State Park campgrounds, north of the Los Angeles County line.

Wildlife ecologist Joanne Moriarty of the park service says the bobcat’s entire “home range,” or habitat area, had been incinerated. “But the biggest thing was that her paws appeared to be burned. She couldn’t hunt or walk very well.”

This bobcat, its paws burned, would later be found dead by hikers as a result of the Springs fire in May.

The bobcat’s death, announced last Thursday on the Facebook page of the park service’s Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, prompted an outpouring of comments lamenting the animal’s fate. One mountain biker, who’d seen the bobcat on the trail, said “it was the saddest thing to have to walk away from [her]. RIP beautiful cat.”

But the death also came with an irony for park service researchers—and a lesson for the broader public living in the region’s tinder-box conditions.

Several years ago, the bobcat—known simply as B274—had been captured, tagged and monitored with 16 others as part of control group for a landmark study of bobcats in the area’s more urbanized areas, such as Thousand Oaks and Westlake Village. There, the animals had been hit with an epidemic of potentially deadly mange. Researchers theorized that the cats’ immune systems had been compromised by eating rats poisoned with anti-coagulants, the most commonly used method of rodent control. Meanwhile, the control group, outfitted with GPS collars and living in the wilds, showed no evidence of mange or other immune problems.

But, in the end, bobcat B274—and probably many others—couldn’t be saved from another modern-day reality: An estimated 94 percent of wildfires in the Los Angeles region’s mountains are ignited not by nature but people acting carelessly, negligently or maliciously. “Even though these bobcats were in a much more natural area,” Moriarty says, “in reality they were still highly affected by human causes.”

According to investigators, the rampaging Springs fire, which came at an extraordinarily early time in the year, was accidentally caused by an “undetermined roadside ignition of grass and debris,” most likely from a passing vehicle.

Moriarty says that bobcats, which are solitary and territorial, are already stressed because their habitat has been sliced by roads and shrunken by developments. Now, with officials this week warning of fire conditions that look to be the worst in a century, she and other scientists worry that the toll on wildlife could be profound, especially with fires flaring earlier in the year because of worsening drought conditions.

Moriarty feels certain, for example, that bobcat kittens were killed in the Springs fire because it came during the “denning” season, when mothers are caring for litters of up to five kittens in the mountain underbrush. Of the 5-year-old bobcat found on the trail, Moriarty says, it’s “very possible she may have had kittens.”

And this, of course, raises broader concerns about survivability. “Anything that affects reproductive timing has huge impacts on a population’s ability to exist,” says biologist Laurel Serieys, who’s been collaborating with the National Park Service on bobcat research and runs a website called Urban Carnivores. “Human impacts on the environment and the wildlife extend far beyond the city boundaries.”

Exactly how many bobcats survived the wind-driven flames that hop-scotched through Sycamore Canyon is unknown. “Definitely, some of them are going to end up perishing,” Moriarty says. Budget permitting, she says, she’d like to set up remote cameras to track possible survivors and document the challenges they’ll surely face.

“As a person, it makes me sad,” Moriarty says of the likely bobcat deaths. “But as a scientist I find it interesting. We’ll have an opportunity to learn how even those who managed to escape are still going to be negatively impacted by the fire.”

National Park Service officials have undertaken the largest study ever of bobcats, monitoring them in the Santa Monica Mountains with GPS collars. Photo/Pete Padilla

Posted 6/20/2013

Bingo! Beach restoration’s a winner

May 22, 2013

Just in time for the unofficial start of summer, Venice Beach has landed some national bragging rights as one of the best restored beaches in the country.

The recognition from the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association honors the $1 million restoration of a 650-yard-long stretch of Venice Beach that was severely eroded by winter storms of 2004 and 2005, and walloped again—although less severely—in 2010.

The restoration—known as “nourishment”—served to widen key areas, protect county buildings, minimize erosion and make it easier for sand to build up naturally during the summer months.

“A year and a half later, we’re looking at super-wide beaches,” said Charlotte Miyamoto, planning division chief for the Department of Beaches and Harbors.

The 2011 restoration project required transporting 30,000 cubic yards of sand from an area north of the Venice breakwater to the damaged area near county lifeguard headquarters, about a half mile south.

Venice Beach shares top honors with six other beaches around the country, including Delray Beach in Florida, Nags Head Beach in North Carolina, Pelican Island in Louisiana, and the Edgartown beach on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts.

Lee Weishar, who chaired the ASBPA committee that assessed the contenders, said that beach restoration funding, particularly from the federal government, has been hard to come by in recent years. But he noted that Hurricane Sandy provided a dramatic wakeup call, with unrestored beaches damaged more profoundly than those that had been “engineered” with restoration projects.

“It’s a hard way to learn that a restored/engineered beach makes a big difference,” he said.

Miyamoto, of Beaches and Harbors, said that as the county plans for climate change, more beach restorations may be on their way.

“These are things that we’re going to have to continue doing,” she said.

Posted 5/22/13

Burning questions

May 9, 2013

When wind-driven flames tore through one of the Santa Monica Mountains’ most scenic canyons last week, hearts sank with visions of another city escape transformed into a smoldering moonscape.

Sycamore Canyon draws thousands of visitors every month with its gorgeous vistas, canopied trees and a network of trails suitable for everyone from strolling couples to hardcore hikers. So the big question was this: exactly how destructive was the fire that ignited near Newbury Park in the inland valley and didn’t stop until it reached the sea at Point Mugu State Park, about 30 miles north of Santa Monica?

Over the past couple of days, some answers—along with new questions—have emerged, as national and state parks experts have hit the charred ground to begin investigating the fallout from the only spring wildfire in anyone’s memory.

What they’ve found might be good news for people eager for a return to the trails but troublesome for the area’s wildlife, especially its birds, now in their prime nesting season. “Normally, with fall fires, that’s not going on,” said fire ecologist Marti Witter of the National Park Service. “There was probably a significant hit to bird populations.”

The rare early timing of the so-called Springs fire also has raised questions about the regenerative resilience of burned trees, which were in their spring growth period and already were challenged by drought conditions. Deciduous trees, such as the sycamores, had yet to begin moving nutrients from their leaves to their trunks, as they do during the late summer and fall months. Those leaves are now scorched or incinerated. At a minimum, experts predict that damaged trees could remain leafless and unsightly for months longer than if the blaze had erupted later in the year during the normal fire season, when subsequent wetter months help force new growth.

“People are going to be looking at a black landscape much longer than they normally would,” said Witter, of the park service’s Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

For now, the public won’t be seeing anything; officials have ordered a two-week closure of the Sycamore Canyon Trail area until an assessment of the potential dangers can be determined. A key player in that process is National Park Service plant ecologist John Tiszler, who, like Witter, also works in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. Earlier this week, he toured the popular lower canyon on behalf of Ventura County fire officials.

“Clearly, the vast majority of it burned,” Tiszler said. “I know people are very worried about this but I don’t think there’s any reason to think that a catastrophe has occurred.”

Tiszler said “the fickleness of the winds” had left some spots unscathed as the flames quickly shifted through the broad lower canyon beyond the undamaged Point Mugu campground. Those scattered green zones, he said, could provide refuge for displaced, nesting birds and such ground wildlife as lizards, which park service staffers are attempting to rescue. (Click here for a satellite image of the “burn scar.”)

Tiszler said that, in the lower canyon, he flagged only 15 sycamores and oaks that had the potential to fall along the fire-road trail. Only three or four of them, he said, should be taken down. But in the canyon’s upper, narrower passages, he said, the toll appears worse because of more intense flames and heat.

The staying power of all those affected trees could be tested in the days ahead, Tiszler said, when high winds are expected to whip through the area again. He also said a looser standard will be applied to damaged trees along hiking trails that don’t have gathering areas, where the public might linger and be at greater risk. “If there’s no person, car or picnic table,” he said, “then the potential of being a public hazard is much reduced.”

Tiszler also noted that trees in Sycamore Canyon had withstood a number of blazes over the decades, including the more devastating Green Meadow fire in 1993. “Trees are like alien beings from another planet,” he said. “They are so different from us, the way they heal themselves, what they tolerate.” He said trees can stand strong even with deep hollows burned into their core because their weight is borne by their outer rings.

Like many veteran hikers and naturalists, Ron Webster of the Sierra Club does not view flames as an enemy of Sycamore Canyon’s trails, a good number of which he helped cut years ago. “You know, it’s just fire. The place greens up and then we’re off again,” said Webster, who, at 78, still leads trail crews in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“Be sure to schedule hikes there in the spring. You’ll see wildflower displays like you won’t believe,” Webster said, noting that seeds have long been lying dormant under the deep chaparral that has been burned away.

Witter of the park service said she, too, has learned to put the area’s fires in perspective. A longtime Topanga resident, she remembers the destruction of property—and the uprooting of lives—from the wildfires two decades ago that cut a fiery path from the mountains around her neighborhood to the ocean’s edge in Malibu.

“Seeing all those burned homes, that was emotionally devastating,” Witter recalled. “This fire has changed the landscape, but it should come back.”

Fire hollowed out the core of this broken oak so its outer rings could no longer support its weight.

Posted 5/10/13

Transforming a prime beach vista

January 8, 2013

The dirt lot overlooking the sand at Coastline Drive and Pacific Coast Highway has been vacant for three decades or so. Once it held a beachfront café owned by the restaurateur who started Gladstones. Then fire destroyed the place twice in five years.

So it sat, roped off and abandoned, little more than a cluster of faded parking spots and wooden pilings, as homeowners resisted the opening of a new restaurant along the already congested highway; after a while, passersby forgot that much of anything had ever been there.

This week, however, the county took the first steps in a $9.5 million plan to re-open the 1.9-acre site and make the beach there more welcoming to the public, starting with a spacious view deck that will not only provide improved passage to the shoreline, but also offer a stunning view down the coast toward Santa Monica Pier.

“This will be a great place to stop and listen to the waves and enjoy the sunset,” said Charlotte Miyamoto, chief of the county Department of Beaches and Harbors’ planning division.

“This will finally make use of an area that hasn’t been visited much,” Miyamoto added. “Right now, there’s a bus stop there and not much more.”

This wasn’t always the case. The site, at the northwesterly end of Will Rogers State Beach across PCH from the entrance to the Getty Villa, was once the location of an oceanfront café owned by Robert Morris, who in the 1980s was one of Los Angeles’ best known restaurant owners.

The spot had had an eatery on it since 1976, when the county had approved a summer concession and snack bar. A later restaurant on the site, Jetty’s, started by Morris and a partner, burned down twice—once in 1979 and again in 1984, according to Coastal Commission records.

After that, hopes dimmed for a comeback; at one point, Morris announced plans to reopen the restaurant, rename it the Malibu Deck and make it part of a proposed “restaurant row” of oceanfront dining on public beaches.

But the pushback was powerful. Pacific Palisades homeowners protested that a new beachfront restaurant would worsen congestion and generate crime, garbage and noise. And the state and county couldn’t agree on a plan for such an enterprise on the site. (Much of the state’s beach property here is operated by Los Angeles County and the lease revenue would have helped the county’s general fund in the midst of a recession, but the state was less enthusiastic at the time.)

Eventually, without a design that met current building and safety codes for the area, the restaurant lease was terminated. The empty lot was roped off and anyone who stopped at the site in hopes of a beach shortcut had to make their way down a steep embankment, where they found little more than those 52 ghostly-looking pilings and a narrow strip of sand.

By the late 1990s, the county had begun to explore ways to reopen the site’s beach access, but it took years to negotiate a workable plan with the California Coastal Commission. Among the sticking points were initial plans to shore up the bluff with a rock-covered, sloping embankment, which coastal commissioners felt was too intrusive. Eventually, the commission called for a 610-foot-long, 15-foot-high seawall that added several million dollars to the cost of the project, but preserved more of the beach.

The current design, approved this week by the Board of Supervisors, will create a refurbished, 26-space parking lot next to a landscaped, 2,100-square-foot public view deck, from which pedestrians can access the beach via an ADA-compliant access ramp.

Construction costs are estimated at $5.76 million, plus some $3.5 million for plans, plan checks, consulting services and other construction costs. The project is set to break ground in April, with completion expected in October, 2014.

Posted 1/8/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink