At the ready for Ebola in L.A. County

Nurses at LAC+USC hospital this week learn how to protect themselves from Ebola with protective gear.

When LAC+USC Medical Center handed out its latest batch of protective gear against the Ebola virus Wednesday, several emergency room nurses eagerly reached out with both hands.

There were impermeable gowns, scarves, booties, hair coverings, face shields, goggles and gloves – boxes and boxes of them. Still, the offered protections were not enough to ease the anxieties of at least a few of the nurses who’d gathered in the facility’s conference room.

After all, two members of their profession had, stunningly, contracted Ebola in a well-known Dallas hospital while extensively treating a patient who would succumb to the deadly disease.

One of the nurses at the LAC+USC training session, for example, worried whether the back of her neck was still exposed after she’d slipped on her blue gown. A tall, male nurse, meanwhile, wondered what might happen if his large feet tore through his protective booties.

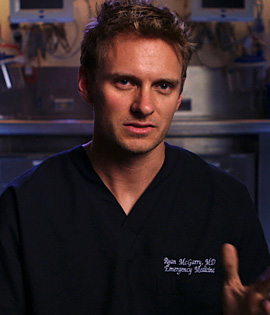

Observing the session was nurse Jason Guzman, 33, who’d already been training for more than a week at the Los Angeles hospital, which is operated by the Department of Health Services. He understood the importance of those questions and concerns because before his training, he had them, too. For with Ebola, even the slightest wardrobe malfunction can lead to infection.

The training, he said, “helped me get more comfortable with the gear. It’s really boosted my confidence. It’s helped me feel a bit better about the situation.”

According to the World Health Organization, the current outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease has infected some 8,900 people, killing about 4,500 of them. That’s more than all other previous Ebola outbreaks combined. Among the casualties: 256 healthcare workers.

Although West Africa remains the epicenter of the disease, the patient in Dallas succumbed after a visit to Liberia, infecting two nurses who’d cared for him.

According to Los Angeles County’s interim health officer, Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, the nurses’ infections underscore the need for healthcare workers and others to take extreme precautions if they come into contact with a patient who may be contagious.

“I feel personally responsible for their safety,” he said.

Ebola, first discovered in 1976, can cause fatal hemorrhagic fever. A person can get sickened through direct contact with an infected person’s bodily fluids. The first symptom is fever, followed by headache, weakness, diarrhea and severe bleeding.

Gunzenhauser is concerned but calm, even unruffled. That may be because he’s not only a doctor but a retired Army colonel, whose resume includes graduation from West Point, medical training at Walter Reed Army Hospital and drafting health policies for soldiers deploying to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He even learned to parachute out of planes, should that be the only way to reach wounded soldiers on the battlefield.

“Coming out of the military, I’m very accustomed to working in highly stressful operational environments and approaching problems with greatly detailed plans,” he said.

Last week, Gunzenhauser and other county leaders convened a task force to evaluate the response to Ebola if it were to reach Los Angeles. He knows that patients would need more than just medical care.

That’s why beyond medical, emergency and law enforcement agencies, the task force includes such departments as Children and Family Services, Mental Health and Public Social Services.

“Let’s say, for example, we might have a case where we would need to quarantine a family,” he said. “How are they going to get their food? What if they need medications? What if we’re pulling a kid out of school? We need to look at all those contingencies, and plan for them.”

If preparing for Ebola is like mounting a military campaign, then nurse Jason Guzman is among those on the front lines. He feels a “calling” to be a nurse, despite knowing that taking risks is “part of the job description.”

“Nurses are in the field to care for those who need help, and Ebola patients aren’t any different,” Guzman said. “They definitely need care — a little bit more care, perhaps.”

“I just know that if there’s a situation where there’s possibly a patient with Ebola, I’m going to do everything i can to help them,” Guzman said. “I’ll also definitely do everything I can to protect myself.”

Posted 10/17/14