She’s the new jailer in town

Terri McDonald, formerly a top California correction’s official, will oversee L.A. County’s troubled lock-up.

Terri McDonald is taking a break in one of her favorite places, the warden’s office at Folsom State Prison. She’s sentimental about the whole place, with its thick granite walls and colorful history as one of America’s oldest operating prisons. Years back, she worked there as a captain. More recently, she’s been overseeing it—along with 32 other California lockdowns—as operations chief for the state’s penal system, the largest in the nation.

On this day, during an interview with a caller from Los Angeles, she sounds more like a social scientist than a prison boss. “They are their own communities,” she says of the state institutions, “each with its own ebb and flow, each with its own subculture.”

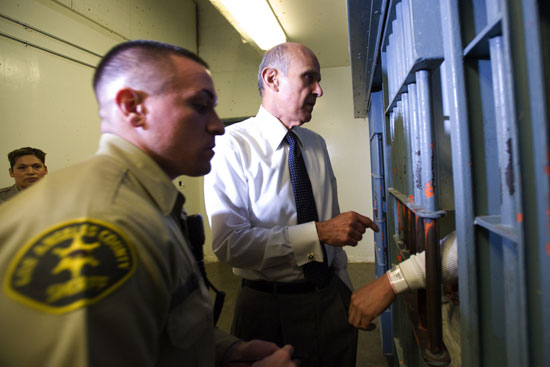

Behind the walls, she says, you’ll find “the most complicated people in California,” men and women “too problematic to be in society,” thrown together with an undercurrent of “gang allegiances and sociopathic influences.” Some inmates might be only 18 years old, she says, others 90. Some may have developmental disabilities, others Ph.D.’s.

“It’s just fascinating,” McDonald says enthusiastically. “I can’t wait to see how L.A. works.”

Come March, she’ll get that opportunity when she assumes her newest—and, arguably, her highest profile—position during a quarter-century career in corrections; McDonald has been selected as assistant sheriff for the custody division of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department—a post created as one of the top priorities of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence. McDonald, 49, also will hold the distinction of being the highest-ranking woman in the department’s history.

“It’ll be a challenge,” she says of the new job, “but certainly not overwhelming.”

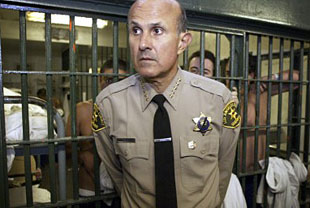

McDonald’s selection by Sheriff Lee Baca represents a significant departure for the department, which historically has promoted from within. The blue-ribbon jail panel stressed the importance of naming an outsider to the new custody position, someone with a record of success in managing a large corrections facility or department. In its final report in September, the panel noted that the previous three assistant sheriffs responsible for custody operations had come from the department’s patrol side “and none had any recent experience in the jails.”

The panel, whose members were appointed by the Board of Supervisors, also recommended that the new position report directly to Baca to enhance accountability and “remove the filtering process that accounts, in part, for the Sheriff not knowing of ‘bad news,’ while at the same time reducing [Undersheriff Paul Tanaka’s] influence over Custody operations.” The jail commission blamed Tanaka for undermining efforts aimed at reducing brutality among some deputies assigned to the county jail system, which is managed by the Sheriff’s Department.

In the wake of the findings, Baca acknowledged management failures of his own and agreed to implement the panel’s 60 recommendations, including conducting a nationwide search for the job McDonald cinched.

“My expectation for her is to tell me the good, the bad and the ugly and to proactively head off problems, solving them before they get out of control,” Baca says. “This was a gap that needed to be closed.”

Baca emphasized, as did the commission, that he has made substantial progress already in reducing the use of unnecessary force in the jail and expects McDonald to build on those reforms and others, including the expansion of inmate educational programs.

The commission’s general counsel, Richard Drooyan, says McDonald “certainly has the experience and background” to tackle the problems uncovered during the panel’s nearly year-long investigation. “I think it helped bringing in someone from the outside to restore credibility to the process,” says Drooyan, who is now monitoring the department’s implementation of the commission’s reforms.

McDonald, who grew up in the small Stanislaus County town of Oakdale, went to work for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation at the age of 25, specializing in inmate mental health issues. Since 2011, she’s been functioning as undersecretary of operations, overseeing adult institutions, parole operations, juvenile justice and rehabilitative programs. Among other things, she says that, because of massive overcrowding, she was responsible for moving 10,000 inmates to five other states, giving her a national perspective on prison models.

During the past year, her state job also has brought her into direct contact—and sometimes conflict—with Los Angeles County. She’s been the California prison system’s point person for “realignment,” the highly controversial shift of certain oversight and incarceration responsibilities from the state to its counties. It’s been her job to coordinate this unprecedented remaking of the state criminal justice system with local probation officials, sheriff’s departments and mental health experts.

Now, she’ll be on the hook for managing the fallout in L.A. County’s jails, where thousands of inmates are being sentenced for crimes that used to land them in state custody—and for terms longer than those previously imposed on county jail defendants. “In my new role,” she says, “I’ll have the opportunity to see the impact and work on solutions.”

As for the scandal of excessive force in the county’s jail that led to her landing the $223,087-a-year job, McDonald says she’s up for the task. She notes, among other things, that she was a “master trainer” for the state’s use of force policy and was instrumental in revamping the training academy’s ethics curriculum.

“I understand the realities of working in correctional environments and how to make fundamental changes,” she says. “I’ve been in situations where I’ve been battered and been in riots. I’ve used force. I think folks have to realize that force is a reality of jails and prisons.” But, she says: “The force used must be the minimum amount to resolve the problem and not used as punishment.”

Posted 2/22/13