Hall of Justice: stately ruin no more

Downtown L.A.’s historic Hall of Justice, damaged in the Northridge quake, is set to reopen.

After a $231-million renovation that spanned a decade, the Hall of Justice — site of Charles Manson’s trial and Marilyn Monroe’s autopsy — will be rededicated Wednesday as the new headquarters of the sheriff and district attorney.

The Beaux Arts landmark, built in 1925 and red-tagged in 1994 because of damage from the Northridge earthquake, has been transformed into a modern-day office building that celebrates its storied past.

“I am thrilled to see this architectural gem restored,” said District Attorney Jackie Lacey, who will move in around December or January. “Although it’s no longer a courthouse, it still will be a place where justice is served.”

Located on 211 W. Temple Street, the hall has been an integral part of Los Angeles’ history and downtown skyline for almost a century.

Designed by Allied Architects in the Italian Renaissance style, it was the first building in the nation to consolidate law enforcement facilities under one roof. The sheriff, district attorney, coroner, public defender and even tax collector have all, at one time or another, maintained operations there.

The 14-story, 550,000 sq. ft. high-rise also had 17 courthouses and 750 cramped jail cells that housed as many as 2,600 inmates at a time.

Aside from Charles Manson, the hall’s most notorious occupants were Sirhan Sirhan, who assassinated Senator Robert “Bobby” Kennedy; mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, and “Nightstalker” serial killer Richard Ramirez.

Daredevil Evel Knievel staged a grand exit from the hall after serving time for assault. He ordered about 20 limousines to pick him up, along with every other inmate released on the same day.

One of the Hall of Justice’s original wrought iron staircases.

The famous and infamous were not relegated only to the jail cells and courtrooms. Marilyn Monroe and Robert Kennedy’s remains were once examined on slabs in the autopsy suites.

When the Northridge earthquake struck in 1994, the hall itself almost became history. With rows and rows of jail cells with steel bars on the uppermost floors, the building was top heavy, so it twisted violently during the magnitude 6.7 temblor. The foundation survived unscathed but the interior walls were rendered unstable, potentially collapsing on people.

The Sheriff’s Department moved to leased offices in Monterey Park and the hall was left to molder until 2004, when the Board of Supervisors voted to authorize its renovation—as long as it was “cost-neutral”—at the urging of then-Sheriff Lee Baca.

LASD Facilities Director Gary Tse said Baca fervently believed the hall was the department’s rightful headquarters. Baca, Tse said, “wanted the department to ‘go home’ — that was how he phrased it.”

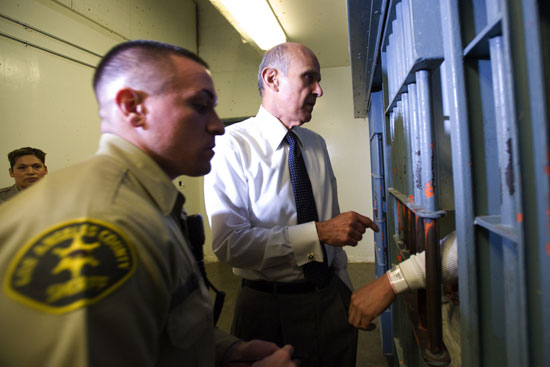

Baca, however, retired early this year amid scandals over brutality in the jails and the indictment of more than a dozen deputies. Now his successor, who’ll be elected Nov. 4, will be based at the hall.

County Chief Executive Officer William Fujioka calculated that the cost of issuing bonds for the renovation could be offset by savings from private leases that agencies would no longer have to pay after moving into the hall.

“The combined annual lease savings from the Sheriff, DA and CEO lease terminations total is $10 million,” he wrote in a report. “These saving will be applied toward the Hall of Justice financing payment costs.”

Contractors with AC Martin Partners and Clark Construction Group gutted the building and even sold the steel from the jail cells to a recycler for about $500,000.

They also merged a couple of floors to leave only 12 stories with 300,000 sq. ft. of usable space to be occupied by 1,600 workers from the Sheriff’s Department and District Attorney’s Office.

(AC Martin Partners’s website has architectural drawings of the hall’s interior design. Clark Construction’s website has photos of the demolition and renovation. Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s website also checked in on the renovation’s progress, with this story and photo gallery. )

The seismic retrofit included reinforcing the building’s four corners with 1,000 tons of rebar, prompting Tse to say the hall is “now probably one of the safest buildings in L.A.” Workers also outfitted the building with state-of-the art mechanical, electrical, plumbing and data systems, and — for the first time — centralized heating and air-conditioning. They even built a bioswale into the landscape to collect and filter water seeping into the aquifer.

Architect Ryan Kristan, a consultant of the county Department of Public Works, was excited about using modern technology to revive an old building he remembers seeing in a black-and-white rerun of the television classic “I Love Lucy.”

“The demolition was loud and messy and very destructive, but once we started putting walls up and modern utilities in, the building felt like it was coming alive,” Kristan said. “And when we turned on the air-conditioning, it was as though the building was breathing again.”

Other new additions include a 1,000-space parking garage erected next to the hall, alongside the 101 Freeway, and a 12-foot-tall bronze statue of Lady Justice to be installed at the main plaza next month.

The county hired conservationists to make sure the renovation did not do away with “character defining” features that made the hall eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

They restored the grand lobby to its former glory, complete with marble columns and gilded ceilings from which hung ornate chandeliers, each weighing about 700 lbs. They power-washed the facade’s Sierra white granite, which had turned a dirty gray, using water infused with miniscule glass beads. The stone now gleams like those at Los Angeles City Hall, built in 1928 — after all, they came from the same quarry. Also preserved were the terra cotta sculptures that embellished the granite. Most of the original windows, doorways with transoms and staircases with wrought iron balusters have also been retained.

“They don’t build buildings like this anymore,” Michael Samsing, who works in asset planning and strategy for the county CEO, said while admiring the antique elevator cabs, now attached to modern mechanisms with digital displays that transport occupants directly to the floor of their choice.

The cell block that once housed Manson and Sirhan has been preserved as part of an historical exhibit. It had to be taken apart piece by piece, and then painstakingly reassembled several floors below its original location.

County Department of Public Works senior capital project manager Zohreh Kabiri said renovating the hall is “way more complicated than starting a building from scratch,” but a great honor.

“The most enjoyable part is to preserve history and not see this building be demolished,” she said. “This is a historic landmark and being part of the team to restore it for future generations is something to be very proud of.”

Sheriff’s facility director Gary Tse, left, and CEO analyst Michael Samsing examine a property map.

The cell block that once held killer Charles Manson has been preserved as a historical exhibit.

The grand lobby’s original elevators are now powered by hidden, modern mechanisms.

After painstaking restoration, the grand lobby now looks like it did when built in 1925.

Posted 10/2/14