Dry time for county’s new storm boss

March 27, 2013

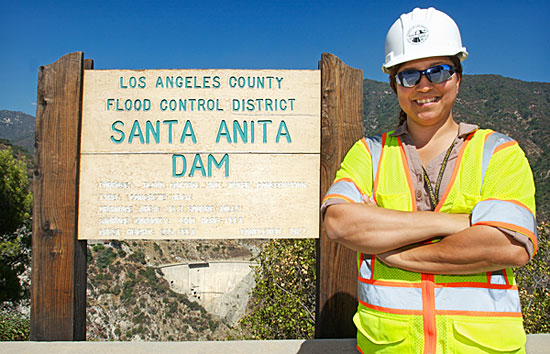

Meet L.A. County's storm boss, Michele Chimienti. Rainfall's been light during her first winter on the job. Photo/Public Works

If this was a normal year, water would soon be gushing from the Los Angeles County dam system’s reservoirs. It would be surging down rivers and channels, rushing into spreading grounds to be filtered and recycled, and flowing through wildlife habitats where it would sustain plants and animals through the long, hot summer.

But this is not a normal year.

For the second season in a row, winter storms have largely bypassed Los Angeles County and much of California. Local rainfall levels so far have reached only 37% of normal levels, and prospects for the kind of sustained, heavy rain required to make up the difference seem increasingly unlikely. (The storm that’s been forecast for this weekend isn’t expected to do much to bring county reservoirs—now holding just 5.5% of what they’d stockpile in a normal year—back up to where they should be.)

What’s more, a “new normal” seems to be emerging. Just ask Michele Chimienti, the county’s new “storm boss.”

“We’re seeing more of the high-highs and the low-lows. Nothing’s really normal. There’s no average,” said Chimienti, a county Public Works engineer who, since October, has been in charge of operations for the department’s water resources section. “You have one extreme or the other. Like in 2005, we had our historic wet year. That’s obviously an extreme. Then we had a dry year last year.”

For consumers, such extremes can be a pocketbook issue, with water rates going up and conservation programs aimed at lowering outdoor water use being heavily promoted—from “Cash for Grass” to “ocean-friendly” gardening.

For the water pros, the seasonal extremes are a challenge to business as usual. As hanging onto every possible drop of rainwater becomes increasingly crucial in Southern California, Public Works is accelerating its efforts to modernize and expand water retention capabilities throughout the region. (A list of completed and upcoming projects is here. Such efforts also are a central element in the proposed Clean Water, Clean Beaches parcel tax; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has asked for more details on the measure before deciding whether to place it before voters next year.)

And for those like Chimienti on the frontlines of storm water management, the dry spell has posed its own kinds of challenges—of the lonely Maytag repairman variety.

“I actually would have loved it if we’d had a wet season. That’s what we thrive on,” Chimienti said. “It does get a little frustrating when we have dry year upon dry year.”

Still, she and her team are using the time in which they’d ordinarily be controlling and diverting fast-moving stormwater to make needed repairs and upgrades to the system.

“This is our downtime right now because it has been such a slow storm season,” she said, “so we’re looking toward the future: what can we do to improve our water conservation in all of our facilities?”

Even though she hit a dry patch in her first winter on the job, the 40-year-old Chimienti has seen plenty of storm activity in years gone by.

“You can volunteer for storm duty, and I did that for the past six, seven years,” she said. “It’s a good way to learn the facilities. You see the river. You see how it reacts. You get a good idea of the amounts of water, the quantity of flow that’s coming down. You get to learn the names of all the flood maintenance guys who actually do this day in and day out, run up and down the rivers, making sure people are out of the flow when water’s coming down, making sure it’s safe.”

Chimienti, the first woman to serve as the county’s “storm boss,” was named a Top Young Leader last year by the American Public Works Association, testament to her work in her previous assignment: project engineer on the $100 million Big Tujunga Dam retrofit.

The work on “Big T,” as the dam is affectionately dubbed within Public Works, focused primarily on bringing the facility up to modern seismic safety standards. But an added benefit was that a reinforced reservoir could hold—and hang onto—much more water in the wet years.

“We’re able to conserve an additional 4,500 acre feet a year,” Chimienti said. (An acre foot is approximately 326,000 gallons.)

That kind of capacity is crucial when the amounts of rainfall vary so widely from year to year. As for what’s behind the variations, Adam Walden, senior civil engineer in Public Work’s water resources division, said they might be attributable to climate change but “we don’t know for sure.”

“What is known is that, in recent years, we are seeing extremes in L.A. County’s rainfall,” according to Walden. “We have had both the wettest year on record (40.5 inches in 2004-2005 season) and the driest year on record (3.6 inches in 2006-2007 season.)”

And that, Chimienti said, means it always makes sense to conserve.

“Don’t waste it,” she said. “It is a vital natural resource, and it’s not limitless.”

Effects of dry winter are visible at county's Cogswell Dam in the San Gabriel Mountains. Photo/Public Works

Posted 3/27/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink