County tastes Bell-style politics

August 10, 2010

Long before the revelations of stratospheric salaries, the residents of Bell were seething—as Arlene Barrera can tell you.

A top property tax official in the L.A. County Auditor-Controller’s Office, Barrera and a colleague were featured speakers at a May meeting of the grassroots Bell Resident Club. Their appearance was arranged by a woman who, in an e-mail to the county, said: “I cannot sleep at night, I cry all the time.” Property taxes, she said, were rising so rapidly in the working-class town that residents were being ruined.

On the night of the meeting in a rundown community center, Barrera felt their pain. “We need your help,” they told her. “A lot of our neighbors are losing their homes. They can’t afford the taxes.”

Barrera by then had seen those tax bills—the doubling of assessments by Bell, the extraordinary level of bond and pension debt for such a small and poor populace. “It was ridiculous,” Barrera says. But she could offer little direct relief to the residents, at least for the moment. These were city, not county, matters, she told them. The county mails the bills but the municipalities control them.

“The crowd was very angry. They felt locked out of City Hall,” says Barrera, who advised them on laws governing public records and open meetings. “I felt really bad. I told them, ‘You guys need to get an accountant.’ “

Beyond the intensity of the rancor, there was something else that caught Barrera by surprise that night—the turnout. She’d been prepped to expect a crowd of as many as 100 but only about 20 people showed up.

“I thought maybe they’d inflated the numbers just to get us out there,” Barrera says.

What she didn’t know was that the events leading up to her appearance were, in a sense, a microcosm of the kind of hardball politics and nasty tactics that had allowed Bell’s leadership to exert control and pocket paychecks that would soon become a national scandal.

—

Nestor Valencia has been a thorn in the side of the status quo.

Three years ago, he created the Bell Resident Club, with a stated mission to “take back our community in an honest and effective manner.” The group holds monthly gatherings, such as the one to which Barrera and Carol Quan of the county Assessor’s Office would be invited.

Twice, Valencia has run for a seat on the Bell City Council, and twice he has lost. Valencia says he is simply an advocate for more integrity and transparency in Bell’s dysfunctional civic life. His detractors say he is disruptive and disreputable.

When it comes to Valencia and his group, the city hierarchy doesn’t seem to shy away from exerting its considerable influence in the community, according to documents and interviews.

When it comes to Valencia and his group, the city hierarchy doesn’t seem to shy away from exerting its considerable influence in the community, according to documents and interviews.

In March, for example, the principal of the Martha Escutia Primary Center in Bell says he was supervising more than 200 youngsters on the school grounds outside when he was summoned to the campus office for an “absolute emergency.”

“There was a woman there and she handed me a letter,’’ says Principal Marcus Billson. He says he was directed to “read this now.” On City of Bell letterhead, it accused Valencia of misrepresenting himself as a city employee in reserving a room at the well-respected Los Angeles Unified School District preschool, where the Bell Resident Club had scheduled a meeting. “We want you to be made aware of potential false misrepresentation and are concerned when individuals represent themselves as city employees,” said the letter, bearing the name of the city clerk.

Billson found the letter curious, at best.

“At no time did Mr. Valencia misrepresent himself,” Billson says. In fact, Valencia has a daughter at the school and is a member of the governance council. In Billson’s view, Valencia is “an outstanding young man who is one of my leading parents and is an example of community leadership.” Billson says he wrote a letter to the city to set the record straight.

The principal says he also received an unsolicited visit from a Bell police officer, who introduced himself as the department’s liaison to the school. The officer, wearing a suit and badge, said he was always available for whatever public safety issues might arise at the school. The conversation then took a turn.

The officer said he “was also there to warn me that there were citizens, primarily Nestor, who were very interested in getting into the middle of things in Bell and didn’t know what they were talking about.”

The impact of the policeman’s warning: “I felt like I was being pressured and I knew I wasn’t doing anything wrong.”

In the end, Billson says, the Bell Resident Club meeting was convened as scheduled at the school in mid-March and drew a raucous audience of more than 200. Meanwhile, the principal says he took the officer up on his generous offer to give a public safety talk to parents at the preschool. “I’ve been trying to walk down the middle,” Billson says of navigating the community’s political minefield.

The following month, the Bell Resident Club began moving forward with its plan to invite representatives from Los Angeles County to attend its meeting to explain why property tax bills were skyrocketing. Once again—this time to greater effect—Valencia and his group found themselves subjected to a campaign of misinformation and dirty tricks that included an inflammatory flier purportedly produced by the Bell Chamber of Commerce with the headline: “DON’T BE FOOLED BY LIARS & COWARDS!”

“A faction of evil-doers with a questionable agenda that hides behind the name Bell Residents Club [sic] is spreading lies about our City of Bell,” it says in one typical passage.

Among many other things, the flier—which was distributed at a food bank and a neighborhood watch meeting—accuses Valencia’s organization of “bringing gang members and other unsavory characters to our community” and of being “dangerous and out to destroy your quality of life in Bell.”

For its part, the Chamber of Commerce has disavowed the flier, calling it a fake.

“It was quite shocking to us,” says chamber President Ricardo Gonzalez. “I think it was done in poor taste.” He said the organization has not, however, tried to determine who was behind the screed, which bore the chamber seal. “We try to focus on the positive things in the community.”

As the May 18 meeting grew closer, efforts to scuttle it intensified.

One day before county officials Barrera and Quan were scheduled to show up, a manager of the meeting hall says he got an unnerving call from a man identifying himself as an officer with the Bell Police Department.

“He said not to rent out the room to Nestor Valencia since Mr. Valencia is a very problematic person,” recalls Marcelino Martinez of the AMORC Cultural Center. “He said Mr. Valencia has nothing to do with the city and to avoid problems I should not deal with him.”

Speaking in Spanish through an interpreter, Martinez says he felt threatened by the man’s “tone of voice and the way he was coming down on me.” Martinez, 66, emphasized that the caller did not provide a name, so he cannot be sure he was actually a policeman.

By then it didn’t matter, Martinez says, because arrangements had been approved by the Cultural Center and the meeting was moving forward as planned.

But not everyone, it seems, was ready to throw in the towel.

On the day of the meeting, Valencia says, he suddenly started hearing from residents who’d received phone calls announcing that the meeting was off. “People were calling saying, ‘I hear you cancelled the meeting tonight.” I said, ‘No, No, No.” Valencia suspects that someone obtained phone numbers from a petition he’d filed with the city, calling on Bell to stop issuing bonds that were increasing the tax load on residents.

That night, for whatever reasons, the crowd for Barrera’s and Quan’s presentation was spirited but disappointingly small. “It just fell apart,” says Valencia.

Afterwards, he says he told Barrera of the efforts to undermine his community organizing and handed her copies of the disputed Chamber of Commerce flier and the City Hall “emergency” document that had been hand-delivered to the preschool principal. “This is what happened,” he says he told her. “Normally, we get many more people.”

As Barrera tucked the documents away, she says Valencia “apologized profusely.”

—

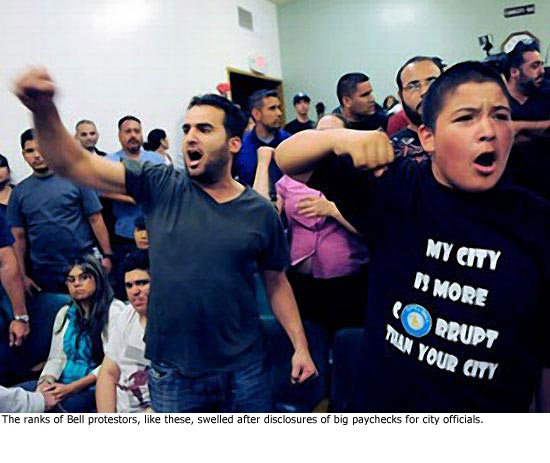

As it turned out, Bell’s residents got something more than an accountant, as Barrera had suggested back in May.

They got investigations by the L.A. County district attorney, the California attorney general and the state controller, among others. And they now have the full-time attention of the county auditor-controller’s office, which has found itself swept up in the media storm.

“For more than two weeks the staff and I feel like we’ve been working for the City of Bell—without the big salaries,” says Auditor-Controller Wendy Watanabe.

As soon as the Los Angeles Times disclosed in July that Bell City Manager Robert Rizzo was making nearly $800,000 and that Police Chief Randy Adams was banking twice as much as LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, Barrera immediately thought back to her night in Bell and those extraordinarily high tax rates from bond measures and city assessments.

“When news of the salaries hit, I pulled down my file and said, ‘This is coming back.’ Maybe this is where the bond money was going.”

Since then, Barrera and her team have been studying Bell property tax bills as though they’re forensic evidence, searching for clues and answers to how the city’s tax rate became the second highest in Los Angeles County—especially considering that its population of 39,000 has a median annual income of only $40,556, which is $17,000 below the county average.

Along the way, besides responding to a daily onslaught of media inquiries, the auditors have turned up some eye-catching findings in their examination of property tax bills in Bell and across the county.

One of their studies, for example, resulted in the surprising finding that, in many cases, the county’s poorer cities have been saddled with higher tax rates than far more affluent areas.

Barrera says her team is now undertaking an ambitious effort to examine the top ten cities with the highest levels of voter-approved indebtedness. The goal, she says, is to ensure that those cities are not spending more than the amount stated in local ballot measures.

“I feel energized,” says Barrera, a 24-year veteran of the Auditor-Controller’s Office, who has been in her current job for only a year. “I see a lot of areas I want to look at.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink