A surf pioneer gets his day in the sun

May 16, 2013

A new holiday celebrating the diversity of Southern California’s beach life has been quietly gathering momentum at the Santa Monica Pier.

Nick Gabaldón Day. The name may not be familiar now, but it’s about to get bigger, starting with an all-day event June 1 on one of Santa Monica’s most storied beaches.

Launched by a group of historians and surf enthusiasts with the support of Heal the Bay and other organizations, the event honors Nicolás Rolando Gabaldón, the first Southern California surfer known to be of African-American and Mexican extraction.

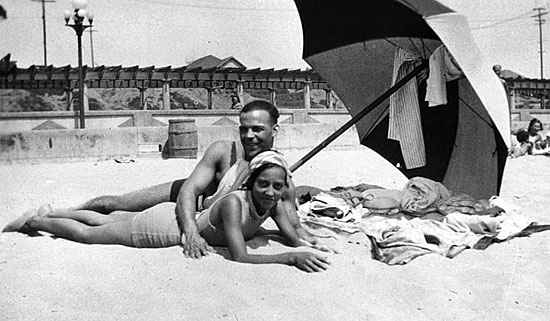

Gabaldón grew up in Santa Monica and surfed on a stretch of shore colloquially known as “The Inkwell” because it was one of the few beaches during the Jim Crow era on which black beachgoers were welcomed. He went on to surf in Malibu with some of the biggest names of the sport’s formative decades.

For years after his death in a 1951 surfing accident, he was all but forgotten, a casualty of the cultural myopia of a racially fraught era. But in recent years, he increasingly has become a rallying point for cultural historians, environmentalists, surfers, inner city groups and others who want the beaches to feel more inclusive.

Five years ago, the City of Santa Monica dedicated a plaque honoring his contribution to surfing, and at least two documentaries since then have focused on his story and the history of African-American surfers. Last year, Heal the Bay and the Santa Monica Conservancy partnered with black swimmers, surfers and divers to combine a coastal cleanup day with a lesson on Gabaldón and the history of The Inkwell, an experiment that led to this year’s more elaborate celebration.

The event, which starts with a paddle-out on the south side of the Santa Monica Pier, will include free surf lessons (click here for reservations), documentary screenings and a beach reception with Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas. Organizers—who include the Black Surfers Collective, the Santa Monica Conservancy, the Surf Bus Foundation, the California Historical Society and Ridley-Thomas’ office—say they are hoping it will lead to an official annual observance.

“Surfing has always been a multicultural activity, but we’ve been denied access through gates that are sometimes legal and sometimes not,” says Rick Blocker, a retired Leimert Park schoolteacher and founder of BlackSurfing.com, a web site that recognizes surfers of color.

Adds Meredith McCarthy, Heal the Bay’s program director: “It’s a way to bring people to the beach who may have never felt welcomed, and a way to start connecting to communities.”

Wayne King, 85, who knew Gabaldón as a Santa Monica High School surfing buddy, jokes that if his friend were still alive, “he’d never believe it—he was just an ordinary guy in the neighborhood.”

King himself was a child when his family moved to Santa Monica from Missouri in 1937. “We were in segregated schools and couldn’t go to school higher than sixth grade back there. My parents knew if we were to have any kind of a chance, we’d have to move to California.”

His father became a welder at Douglas Aircraft Co., King says, and the family settled near 19th Street and Delaware Avenue, in a neighborhood of mostly black and Latino families. King liked to swim, having learned while playing on rafts in the Mississippi River. The Gabaldóns—they were divorced, he says, and Nick lived with his African-American mother—lived a few blocks from the King house. Inevitably, the boys met on the sand.

Today, he notes, his old local beach is one of the swankiest on the Westside, situated between Bay and Bicknell streets just south of the Casa del Mar hotel. In those days, however, it was much narrower and rocky. Nonetheless, on weekends, the sand filled with African-American and Latino families, and the kids who were fortunate enough to live within walking distance developed a level of comfort there that their inland contemporaries didn’t share.

Over time, he and Gabaldón made friends with some white lifeguards who had noticed that the two boys enjoyed bodysurfing.

“They had one of those big, old-time wooden boards and asked us if we were interested, and they and a couple of other kids in the neighborhood, the Pilar brothers, taught us to board surf,” he remembers. It was “exhilarating”, he says, and eventually, he and Gabaldón bought their own boards and began looking for bigger waves to tackle, a challenge that drew the easygoing young black men into a culture that was dominated by white and Pacific Islander surfers.

It also forced Gabaldón to eventually buy a car, King says, because motorists on Pacific Coast Highway were so reluctant to pick up a black man. At least once, he says, Gabaldón told him he’d paddled all the way from Santa Monica to Malibu on his surfboard, a legendary trek that inspired the name of one of the documentaries about him, “12 Miles North: The Nick Gabaldón Story.”

“We were like a pair of flies in a bowl of buttermilk,” he laughs. “But we didn’t really get a hard time from other surfers. People who hang around the beach are a different breed—they might look at you funny at first, but once you got in the water, you were all the same.”

The two remained friends as Gabaldón joined the Navy, then returned home to attend Santa Monica City College. King recalls being on the beach the day his friend died.

“It was 1951, the first week of June,” King recalls. “He decided he wanted to shoot the pier, go in between the pilings. All of a sudden, this rogue wave came up and he disappeared.”

King, who now lives in Altadena, eventually became a 32-year City of Santa Monica maintenance worker. “I spent 11 or 12 years cleaning those beaches, and I never went back in the water,” he says now. “Seems like after Nick passed, I just lost interest.”

Others did not, however. After Surfer magazine did an article on black surfers that mentioned Gabaldón in the early 1980s, Blocker began questioning his Malibu surfing buddies.

“People said, ‘Oh, yeah, that black guy in the ‘40s and ‘50s? Yeah, he was here.’ Well, to me, that attitude seemed wrong. His story seemed to me like one that needed to be remembered.”

So, picking up where Surfer magazine had left off, Blocker began writing, and his research found its way to Alison Rose Jefferson, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant and doctoral candidate in history at UC Santa Barbara.

Jefferson, who was researching race and the history of Southern California’s leisure spaces, had her own interest in Inkwell beach and the community around it. Her work, and that of Blocker, in turn, drew the attention of Heal the Bay, which last year involved Blocker in efforts to toughen pollution limits in the county’s municipal storm water permit.

Jefferson views the interest in Gabaldón as part of a broader move to reclaim history among groups who have felt left out. But, she adds, raising his profile through alliances like this one also broadens the influence of groups like Heal the Bay, and reminds African-Americans and Latinos throughout the region that they, too, have history with California’s coastline and a stake in what becomes of it.

“Nick Gabaldón was a quintessential Californian. He’s multi-ethnic, part of his family immigrated to this country, and he participated in the California dream, pursuing his passion,” she says. “And people of color want clean water, too.”

Posted 5/16/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink