Among the fallen heroes, two dogs rest

May 26, 2011

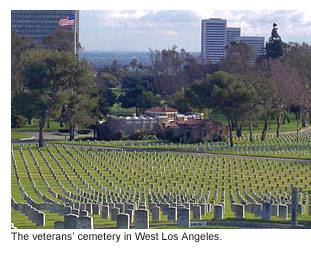

In all the solemn grandeur of the Los Angeles National Cemetery, with its stirring rows of white grave markers and leafy glades, the final resting places of Bonus and Blackout are footnotes, really—unmarked and all but forgotten.

In all the solemn grandeur of the Los Angeles National Cemetery, with its stirring rows of white grave markers and leafy glades, the final resting places of Bonus and Blackout are footnotes, really—unmarked and all but forgotten.

But something about the two dogs—the only canines believed to be buried on the West Los Angeles grounds—captured the imagination of Dan Leyva, the cemetery’s longtime foreman. Who were these dogs, laid to rest during separate ceremonies in the mid-1940s, and how do they fit into the cemetery’s story?

So several years ago, Leyva rode a bus to downtown Los Angeles, went into the Central Library and asked to be directed to the oldest newspapers they had.

Painstakingly, over the course of three hours, he went through old issues of the Santa Monica Evening Outlook until he found them—short articles explaining how Bonus and Blackout ended up finding their final resting places among some of the cemetery’s legendary dead, including more than 100 Buffalo Soldiers, the father of Wyatt Earp and an impressive roster of Medal of Honor recipients. (A more detailed list is here.)

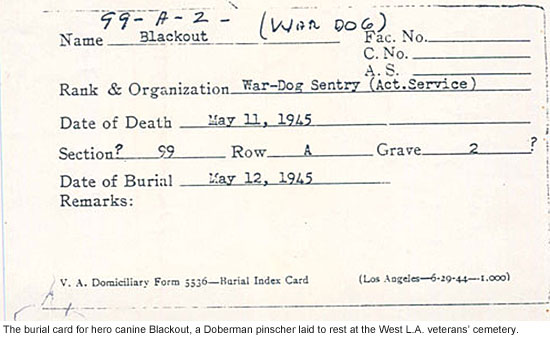

Blackout, it turns out, was a real war hero. The 5-year-old Doberman pinscher had been assigned to duty as a war dog sentry during WWII. After nearly two years of service, shell-shocked and suffering from more than a dozen wounds sustained on the frontlines, Blackout returned to Los Angeles to great acclaim, earning a citation ribbon from the American Kennel Club. But “in spite of all that veterinary science could do for him,” the article said, Blackout never recovered and had to be euthanized.

The headline on the article, dated May 12, 1945, read: “Military Funeral Given Canine Hero.”

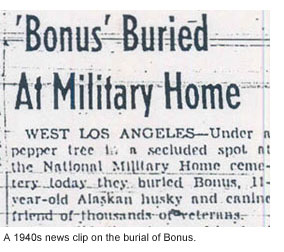

Bonus, on the other hand, was no angel—although he’d evidently been deeply loved by the retired soldiers whose companion he’d been at the Sawtelle Soldiers Home. The 11-year-old Husky, who died of poisoning, had actually been barred in life from the cemetery grounds because he’d bitten two guards there. Leo J. Britt, a World War I Purple Heart winner, took a lead role in the dog’s burial “under a pepper tree in a secluded spot” on May 3, 1943, according to the newspaper account:

“Bonus’ funeral was simple. While a group of veterans stood with bowed heads, Britt placed a robe, a collar and his last box of dog biscuits on the wooden casket, on which had been lettered in gold, ‘Bonus—Our Beloved Friend.”

War dogs are still a part of the military, playing a role in the recent Navy Seal raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound, for example. And another noble military animal is at the center of the hit play “War Horse,” now winning rave reviews in New York for its depiction of a cavalry horse during World War I.

But burial of animals is no longer permitted at the cemetery, which was dedicated in 1889 on land that also housed the Pacific Branch of the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The site, located at 950 S. Sepulveda Boulevard in Westwood, has grown over the years to its current 114 acres.

On Memorial Day, Monday, May 30, a program honoring the men and women who gave their lives for their country is scheduled for 10:30 a.m. at the cemetery. Those with an interest in the facility’s canine history might want to add a side trip to their visit. They will find Bonus buried with his handler, Charles E. Temple, an ensign in the Navy Reserve, in Section 101, Grave 1, Row A. Blackout is buried with George Lewis Oshier, a Navy cook and Marine Corps sergeant, in Section 99, Grave 2, Row A.

Leyva, who served for 8 years in the Navy before beginning his 32-year career at the cemetery, said that visitors seldom inquire about the dogs.

“People usually don’t ask us. Nobody really knows about it,” he said.

But he thinks there’s something about the dogs’ service that is worth remembering.

“Especially Blackout, to me, is kind of like a hero,” Leyva said. “He protected our troops and came back home.”

Posted 5/26/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink