Next stop? A milestone in public art

April 11, 2013

Donald Lipski's "Time Piece," part of Metro's signature art collection, greets bus travelers at the El Monte station.

As art collections go, it’s impressive, from famed sculptor Jonathan Borofsky to activist/artist Judy Baca to renowned Eastside painter Frank Romero.

The catch? You have to be traveling to see it. Oh, and a lot of it is literally underground.

The sprawling exhibition of public art that Metro has built in L.A. County’s subway, bus and commuter rail stations will celebrate its 25th anniversary next year. (Take a virtual tour in our gallery below.)

Launched in 1989 with a half-percent set-aside from rail construction costs, Metro’s award-winning collection of public transit art now encompasses work by some 120 artists in 100 stations, plus posters, photography, poetry and other temporary installations by another 180 artists. Last week, eight California artists were selected to create work for the second phase of the Expo Line, which will run to Santa Monica from the end of the first segment at Culver City.

“Art brings a unique vibrancy and vitality to L.A.’s Metro system,” says Maya Emsden, deputy executive officer for creative services at Metro, who is one of a handful of co-authors on a forthcoming American Public Transportation Association “best practices” paper on integrating art into public transit.

“Art was an integral part of the Metro rail planning process from the very start.”

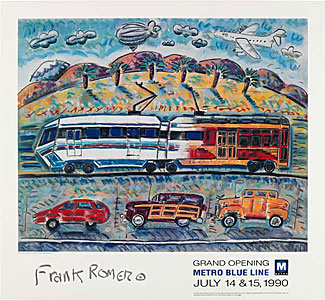

Metro’s collection kicked off in 1990 with a now-highly-collectible poster by Romero to commemorate the opening of the first Metro rail line. That inaugural artwork, which depicts an old Red Car morphing into the Blue Line as classic cars, blimps and airplanes whiz around it, was followed the next year by “Unity,” a glowing, blue-and-white permanent installation of 82 fiber-optic light panels in the subway tunnel between the Metro Center and Pico Stations by Thomas Eatherton, an artist from Santa Monica.

That piece led in 1993 to a series of now-iconic permanent artworks: Borofsky’s “I Dreamed I Could Fly,” a collection of life-size fiberglass figures suspended from the ceiling of the Civic Center station; Terry Schoonhoven’s Union Station mural of “time-scapes” from Spanish galleons to Carole Lombard, sitting on a suitcase; Joyce Kozloff’s ceramic tile “film strip” murals in the 7th Street/Metro Center station; Stephen Antonakos’ hanging neon artworks at the station below Pershing Square.

Since then, the program has expanded with L.A.’s transit system, says Emsden; the new commissions for Phase 2 of the new Expo Line were selected from some 400 submittals and include such artists as Shizu Saldamando, Abel Alejandre, Susan Logoreci, Nzuji de Magalhaes, Constance Mallinson, Carmen Argote, Judithe Hernandez and Walter Hood.

Though the half-percent of construction costs that L.A. reserves is substantially smaller than transit art set-asides in Boston, New York, Portland, and most other cities with such programs, Metro has been able to stretch its allotment by integrating the artworks as much as possible into the station construction.

“One of the ways we’re able to maximize the limited budget is through early involvement in the project,” says Emsden. “This also ensures important art-related things like lighting are integrated into the station plans.”

The added efficiency of building art into a station, as opposed to going back later and retrofitting, is just one of a number of art lessons Metro has learned in the past 24-plus years. Art program staffers have learned to work closely with architects, engineers and maintenance staff to situate pieces so that maintenance of the art is taken into consideration—a matter that can be trickier in, say, a rail station than in a museum.

“The Borofsky piece, ‘I Dreamed I Could Fly’, is one of my absolute favorites,” says Emsden. “But if we were to do it again we’d make sure the figures, which are actually self-portraits of the artist, were hung in a way that we could lower them for cleaning.” The flying fiberglass figures—like everything else in the stations—get covered over time with magnetic steel transit dust that can only be removed with specialized equipment and cleansers, says Emsden.

“So every five years or so, we get up there and clean them between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m.”

Another lesson: Some kinds of art fare better in transit settings than others.

Eatherton’s 1991 light piece, for instance, has been out of order for about six years, due to the technical challenges of maintaining aging electrical elements in a hard-to-reach space. Part of a Jacqueline Dreager sculpture at the Blue Line’s Wardlow station had to be taken out because it was too close to a landscaping sprinkler and was slowly being decomposed by the water. A set of Gilbert Lujan benches at the Hollywood/Vine station had to be refurbished and then eventually removed altogether because vandals kept tagging and carving their initials into the sculpted bench backs.

However, the vast majority of the Metro projects have fared well, says Emsden, adding that even delicate images have been made transit-worthy by rendering them in materials that are sturdy enough for public artwork.

“We’ve commissioned a couple of artists whose whole body of work is on paper, but there are some amazing artisans in L.A. and elsewhere who can translate those artist’s visions into very durable materials,” says Emsden.

For example, one Canadian studio that specializes in mosaics has made detailed lino-cut prints by Sonia Romero and Daniel Gonzalez, paintings by Samuel Rodriguez and photos by Pitzer College associate art professor Jessica Polzin McCoy into intricate Metro panels made of ceramic tile.

Meanwhile, she says, the program has yielded some pleasant surprises. One was the groundswell of interest among local culture enthusiasts asking to do guided art tours. The result, in 1999, was a Docent Council whose volunteers have introduced more than 30,000 people to the art of the Metro system. Notes Emsden: “We’re the only transit agency with volunteer docents and free Metro art tours.”

Perhaps the nicest surprise, however, has been the way in which some Metro pieces have worked their way, just by word of mouth, into the public imagination. “There’s a light piece by the artist Bill Bell that, if you say a secret word into a tiny hole in the wall at the top of the escalators that go down to the Red and Purple Lines at Union Station, the piece will speak back to you,” Emsden says.

There’s no sign. There are no instructions. The artist, by design, held back the “secret word” (the names of any of the various celebrities depicted, from Rin Tin Tin to Dizzy Gillespie) and left no clue that any extra magic might be found there. “But I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen someone going past there—a security guard, a commuter, a business person—and saying to the person next to them: ‘You gotta check this out!’ ”

Jonathan Borofsky’s “I Dreamed I Could Fly” is an iconic—though hard to clean—part of the Civic Center Station.

Public art and public transit come together in the following gallery. All images courtesy Metro.

Posted 4/11/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink