Learning lessons by HeArt

October 7, 2010

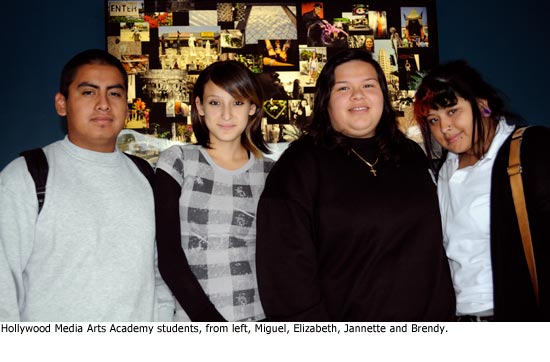

Brendy Giron, a.k.a. “Jinxie,” ditched school daily to tag with her boyfriend. Her classmate, Janette, cut class to chill by the gym.

Miguel Hernandez was so brazenly truant that sometimes as he sneaked out the school door, he’d pass his own mother, who would stake out the campus entrance in a vain attempt to intercept him. Outside, his girlfriend, Elizabeth, would be waiting, having blown off her classes as well.

This is how high school kids end up in alternative and continuation schools in Los Angeles County, which is where all four teenagers eventually landed. Their new classroom, however, is no ordinary alternative.

Every morning, they get five hours of regular classroom instruction; then, in the afternoons, artists come in to teach painting, photography, video production, dance, water color and other arts courses. If they show promise—and stay in class—they have a shot at internships at production companies and art institutions.

“This is an arts high school specifically for alternative education students,” says Cynthia Campoy Brophy, proudly striding down a bright blue hallway in the Hollywood Media Arts Academy.

Jointly run by the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) and The HeArt Project, a nonprofit founded by Campoy Brophy that has offered arts programs to at-risk students in the county for 18 years, the academy is the newest—and smallest—public school of the arts in L.A. County.

The academy has been open for a year and a half, although the HeArt Project took over the arts component only a few months back; an open house to celebrate the new school year was held in September. Current enrollment is around 30 students, but officials hope that, as the word gets out, that number will increase.

“What we’re trying to do is use The HeArt Project and artists who work with the kids to inform and really engage them at a deeper level of career opportunities in the entertainment industries,” says Gerald Riley, assistant superintendent of educational programs at LACOE.

Situated in a low-slung building off Santa Monica Boulevard, the school looks a lot like the show business warehouses that surround it. Inside, however, its rooms are spacious and airy, the walls freshly painted in bright colors and covered with words intended to inspire ambition: sound engineer, director, percussionist, cartoonist, costume designer. The lettering over the doorway in the bright yellow lobby warns, “You are entering a creative space.”

Campoy Brophy, executive director of The HeArt Project, said the split school day is modeled after the more renowned Los Angeles County High School for the Arts, colloquially known as LACHSA. : “The students here have 10 hours of arts programming a week,” she says. “They do their core curriculum in the mornings and we get them in the afternoons.”

Unlike LACHSA students, who must audition and submit portfolios of artwork, however, the Media Arts Academy kids usually have no prior art training and find the school via guidance counselors or word of mouth. Often, Campoy Brophy says, they’re the sort of students “who only come to school on the arts day”—creative but struggling kids who, for a variety of reasons, are failing to thrive in conventional high schools.

Unlike LACHSA students, who must audition and submit portfolios of artwork, however, the Media Arts Academy kids usually have no prior art training and find the school via guidance counselors or word of mouth. Often, Campoy Brophy says, they’re the sort of students “who only come to school on the arts day”—creative but struggling kids who, for a variety of reasons, are failing to thrive in conventional high schools.

Some have had chaotic home lives. Some have trouble saying no to peer pressure. Some have just sold themselves short or missed too much school or fallen in with a bad crowd.

“They aren’t necessarily problem kids, they just need a smaller setting,” says Principal Jennifer Flores, who oversees the academy and six other alternative schools for LACOE.

Student poetry on the walls of the dance room hints at their journeys: I am random and loud/I pretend I’m a makeup artist… I am handsome and nice/I pretend to be Ronaldinho… I am funny and nice/I worry about my homies…

“They come from all over,” smiles Elizabeth Meza, who works in the school office. “Koreatown. Santa Monica. Pacoima. One boy came in every day from Norwalk on public transportation. He said he liked it because it was a safe place for him and the art kept him out of trouble. He’s going to graduate in December, and he’s going to community college, I hear.”

Brendy Giron says she was a middle school student in the San Fernando Valley when her mother began moving around in search of a better job. They ended up in Koreatown, and Giron enrolled at Los Angeles High School, where she met a boy in her second period class who shared her fascination with graffiti art, or, as they termed it, “graf.”

“He had this thing on his notebook, and I go, ‘Oh, you’re a graffer,’ and he’s like, ‘Yeah, what do they call you?’ And I told him what they call me, which was Jinxie. And he was called Obie. And we were all in, like, the love zone, and when he would go writing, I would go writing, too.”

But their habit took on a life of its own, she says. She spent less and less time in classes. She switched schools, but jumped the fences to be with him. She tried independent study and ditched the test days.

One night, she says, she got caught tagging on a mid-city rooftop. Meanwhile, her boyfriend was getting into his own scrapes. Eventually, their pastime became less novel. When her boyfriend told her about the academy, where he had been enrolled for a time, she begged her mother to let her go there. The boyfriend ended up in a juvenile probation camp, but Giron, now 18, says she hopes to study fine art someday.

“I don’t want people to look at my art and be, like, ‘Oh, that’s just tagging.’ I want to do it right, you know?”

Other students see the academy more as a place to learn a new skill. Janette—who school officials insisted be identified only by her first name because she is 16 and a minor—says the promise of art at the end of the day kept her in the classroom: “There was nothing at my other schools that I was that interested in.”

For Elizabeth, 17, the academy has been a lifeline: “I don’t know where I’d be if I didn’t come here. It got the point where my old school didn’t want me and I just didn’t care anymore.”

The school was reluctant at first to admit her to the same school as her boyfriend, but she has applied herself, and for the first time in her life she is earning As and Bs in academic classes. “I just entered the 10th grade, which for me was a big deal. I have a lot of catching up to do.”

Her boyfriend, 18-year-old Miguel Hernandez, says he has stopped cutting class (a relief to his parents) and is hoping to win an internship after he graduates in December. Campoy Brophy says she has been talking to a commercial television production company about the student. As it turns out, she says, he has a knack for cameras.

“Honestly, I didn’t want to come here at first,” he recalls. “I thought it was going to be just another continuation school where they give you a packet of work and tell you to sit down and do it.” But during the summer, he learned photo editing and photography, “and I loved it.”

“It’s like, you can pass by someone or something a thousand times and you wouldn’t pay attention to it. But with pictures, you learn to pay attention. You see things in a different way—a better way.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink