Curtain call for Hollywood costumes

January 26, 2011

Like many stars of a certain age, they no longer get out much. Still, as Oscar season approaches, they deserve their due. Some made history with Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin. Some were themselves Academy Award-winners.

True, most have spent the past several years in a vault in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. But the 250 or so historic movie costumes—owned, improbably, by Los Angeles County—represent one of the most well preserved aggregations of stardom in Hollywood.

“The bulk of people don’t know about it, but it’s a very important collection,” says Glenn Brown, archivist at the MGM Corporate Archives. “Its pieces are from some of the earliest days of film, things from the ‘20s and ’30s, donated by the stars themselves. Things you hardly ever find anywhere.”

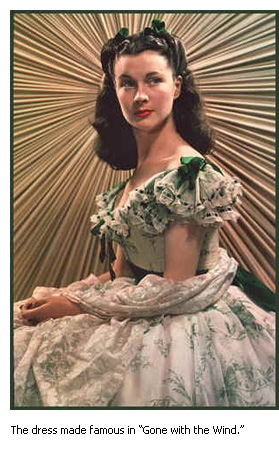

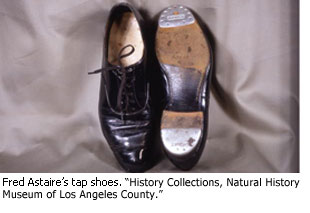

Chaplin’s “Tramp” costume is there. So are Fred Astaire’s tap shoes, Charlton Heston’s “Ben Hur” tunic and the green-sprigged dress (battered but unbowed) that Scarlett O’Hara wore in “Gone With The Wind” at the barbecue at Twelve Oaks. There’s also the pink Howard Greer ball gown that Pickford wore in her first talkie, “Coquette.”

The Natural History Museum has amassed not only many of the most important costumes from the earliest days of the movies, but also a trove of historic film props and other movie mementos, from Lon Chaney’s makeup kit to preserved locks of Pickford’s golden hair, lopped off when she famously bobbed it. Back in the day, such items were considered so insignificant that studios routinely burned, tossed or reused them.

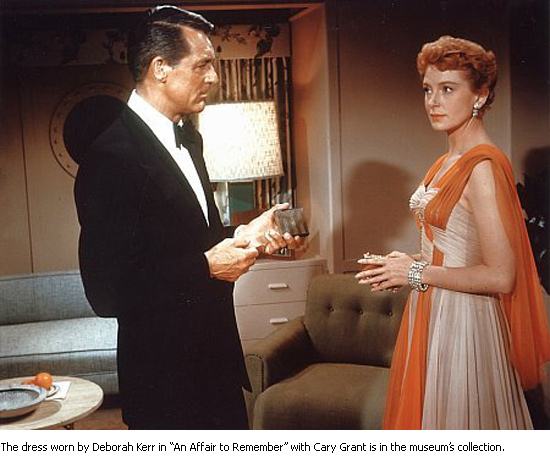

Beth Werling, who manages the collection along with a wide range of three-dimensional artifacts for the museum, says it’s “the biggest collection of its kind in a public institution.” That “public” qualifier is important, historians say, because in recent decades, Hollywood memorabilia has become increasingly privatized at institutions like the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising and in individual collections, such as one owned by actress Debbie Reynolds.

“Things are everywhere,” says Shelly Foote, a longtime historian in the Smithsonian Institutions’ costume collection. The county’s collection is essential for pieces from the ‘20s and ‘30s, says Foote, who turned to the Natural History Museum in researching her forthcoming book on the designer Greer.

Of course, a public institution best known for dinosaurs and rock collections might be the last place most people would go digging for Hollywood glamour.

“But when the Natural History Museum was founded in 1913,” says curator Werling, “it was called the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art. So we’ve collected Los Angeles history since the very beginning.”

The movie collection began in 1930, she says, after studios and stars in the nascent industry began donating items—some just to get rid of them, others because prescient museum officials felt they might be of historical significance someday.

“The then-curator simply contacted everyone and anyone in the industry at the time and asked for donations,” says Werling. Typically, she and others say, such requests elicited shrugs and amusement.

“Costumes were a means to an end,” explains Deborah Landis, director of the David C. Copley Center for Costume Design at UCLA. “The movie was all that mattered. Just as sets are broken up and props go back to the prop house, costumes were reused and re-dyed, and the hems were cut and remade, and nothing was kept because nothing was valued.”

Werling credits that benign disregard for the museum’s unparalleled cache of Chaplin memorabilia, donated for the most part by the actor himself.

“He was a very, shall we say, cautious individual when it came to money and I don’t think he would have ever given anything away if he had any idea what these items would later be worth,” says Werling.

“But the motion picture industry was only about 25 years old then, and it was the beginning of the studio era. It was still being argued whether it was even an art form. And I think people were just flattered to think that anyone saw what they were doing as something worth saving.”

As a result, the county’s collection ranges from the roller skates Chaplin wore in “Modern Times” to his burlap boots from “Gold Rush.” “He donated his Tramp costume from ‘City Lights’ and, as a result, we have the only complete one in still in existence,” Werling says.

Since then, she says, items have come from a variety of sources. Carl Laemmle, who founded Universal, donated a number of early items. A more recent cache came from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art after curators there refocused their costume collection more on couture and fashion. Still others were donated by collectors who decided their items deserved museum-level care.

A motion picture costume is more than just clothing, says veteran costume designer Jeffrey Kurland, who designed the costumes from last year’s sci-fi thriller, “Inception”.

“It’s character-driven. It helps build a visual picture of a character,” he says. “Think of Scarlett O’Hara in ‘Gone With The Wind’ in that barbecue dress, that garden print, so young and frivolous and puffy. That’s how we meet her. And then watch the progression as war comes and her character changes.

“The clothes become slimmer and tighter, until there she is toward the end, in that garnet red dress with Rhett Butler. Think of the line, the fit, the silhouette. Look where she has finally traveled. The clothes show her character’s arc.”

“The clothes become slimmer and tighter, until there she is toward the end, in that garnet red dress with Rhett Butler. Think of the line, the fit, the silhouette. Look where she has finally traveled. The clothes show her character’s arc.”

Local museum-goers have seen little in recent years of the county’s collection, partly because of space constraints and partly because of the fragility of the costumes themselves. The barbecue dress from “Gone With The Wind”, for example—which came to the museum from LACMA—is undergoing extensive repair work because time has all but shattered the costume’s lining, says Werling.

But mostly the collection has remained backstage because of an ongoing rebuilding and transformation project leading up to the Natural History Museum’s 2013 Centennial. So far, the initiative has restored and seismically retrofitted the Beaux Arts museum building and added the new “Age of Mammals” exhibit. But construction has closed the small area where the costumes used to be shown, a few at a time, in glass cases.

A new California history hall is expected in late 2012, just before the museum’s centennial celebration. When it opens, the public can expect to see a lot more of Hollywood, says Werling. Until then, the public’s best hope is to look for the items that are frequently placed on loan to other exhibitions.

Or look for events like the one set for February 4-5 at William S. Hart Park in Newhall—a “ChaplinFest” celebrating the 75th anniversary of “Modern Times,” whose closing scene, with its poignant rendition of the song “Smile,” was filmed nearby on the Sierra Highway.

It was one of Chaplin’s most important films, depicting the tragicomic breakdown of a factory worker beset by the dehumanization of the industrial era. At one point, in fact, the Tramp is swallowed up by the giant gears of the assembly line and run through the machine in his striped workman’s outfit.

On display at Hart Park will be those iconic overalls Chaplin wore—ready for their close-up, even now.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink