Turning 50, to applause

April 3, 2014

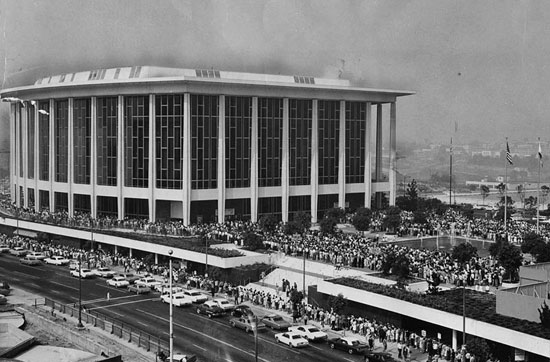

Within a year, the Music Center was a cultural fixture in L.A. Here, thousands of people line up for "Hello, Dolly" tickets. Photo/Herald Examiner

Like any grand dame, she avoids dwelling on birthdays. Still, a half-century is a milestone for a cultural icon in L.A.

So fans of the Los Angeles Music Center have gotten off to an early start in celebrating her upcoming 50-year mark. This week, a launch party on the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion stage kicked off a months-long celebration that will include some 60 large and small programs, including a gala on her December 6 golden anniversary and a public bash the next day on the Music Center Plaza.

“The Music Center has been critical to Los Angeles’ culture,” says Board Chair Lisa Specht. “We’re one of the top three performing arts centers in the country, along with Lincoln and Kennedy Centers, and for decades, we’ve been a hub of creativity.”

Not to mention a game-changer for L.A.’s metropolitan evolution.

“The Music Center was a major turning point in L.A. coming into its own in the postwar era as a major American city,” says Teresa Grimes, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant who has documented the Center’s architectural heritage for past restoration projects.

Though the Los Angeles Philharmonic had been well established, it had no permanent home at the end of World War II other than the Hollywood Bowl, which was forced to close in 1951 due to a financial crisis, Grimes says. A series of “Save the Bowl” concerts, orchestrated by Dorothy Buffum Chandler, the wife of the Los Angeles Times’ publisher Norman Chandler, reopened the beleaguered band shell, but underscored the cultural shortcomings of the burgeoning city.

The winners of a Cadillac Eldorado, part of Dorothy Chandler's fundraising drive for Music Center construction.

Between 1951 and 1954, plans for a civic auditorium and convention center had been put on the local ballot three times, but never garnered the two-thirds majority it needed for passage. So in 1955, Chandler and the local Symphony Association began raising private funds for a hall to house the Philharmonic, which for years had been playing in leased space. As the highlight of their gala kickoff at the Ambassador Hotel, they raffled off a new Cadillac El Dorado.

“That was the beginning of it all,” Chandler is quoted as saying in Grimes’ Historic American Buildings Survey. “When we raised $400,000 in a few hours on El Dorado Night, I knew southern Californians wanted a music center badly enough to build it themselves.”

The effort took nearly a decade, at a time during which Downtown L.A. was being radically redeveloped. It required legislative approval and involved civic leaders from Donald Douglas to the Irvine family to Cecil B. De Mille.

Led by their arm-twisting society matron and her family newspaper, the Music Center boosters powered through social barriers dividing the Pasadena elite from Westside show business people, overcame pushback from provincial politicians, outlasted an economic downtown and triumphed in a last-minute squabble over whether the Center would be situated at First and Hope Streets, where the county wanted to put it, or at Chandler’s preferred location, the summit of Bunker Hill.

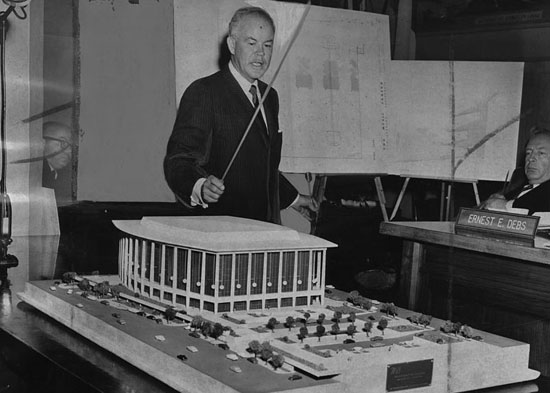

Chandler won, bumping the planned Department of Water and Power Building to the next block as the once-stately—and by now shabby—community of Bunker Hill was razed beyond recognition. She also brought on the architect of her choice, Welton Becket, who had worked with her on the Hollywood Bowl comeback and had master planned the campus of UCLA.

When Chandler decided during a visit to Europe that a single concert hall wouldn’t suffice, and that the new facility would do better financially if it also had a theater and a smaller forum, she won that battle also. Eventually, her tenacity in the project would put her on the cover of Time magazine.

The ultimate cost of the project was $33.5 million, with some $19 million of it from private contributions, including more than $2 million in small cash donations that local citizens dropped in so-called “Buck Bags” that were designed by Walt Disney and placed at cultural gatherings.

On December 6, 1964, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion opened, resplendent with its crystal chandeliers and gold-leaf ceiling; the Mark Taper Forum and the Ahmanson Theatre were dedicated two years later. Opening night featured the renowned violinist Jascha Heifetz performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by a 24-year-old Zubin Mehta.

In the ensuing years, everyone who is anyone has performed at the Music Center, from Ingrid Bergman and Nat King Cole to Neil Young and Ravi Shankar. Esa-Pekka Salonen and Simon Rattle made their American debuts at the Music Center, as did groundbreaking productions from “Angels in America” to “Zoot Suit.”

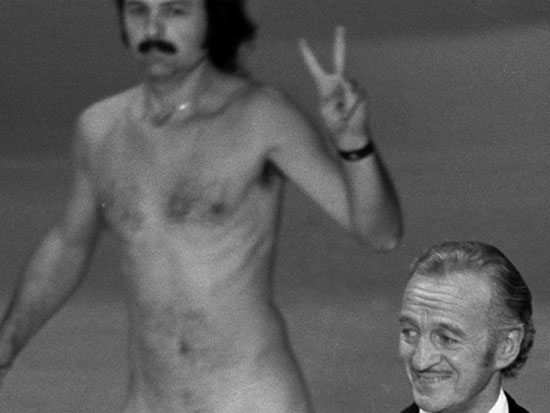

Between 1969 and 1999, most of the Academy Awards ceremonies were held there. The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion is where Sacheen Littlefeather refused Marlon Brando’s Oscar, where a naked man streaked onto national television behind David Niven and where Sally Fields exalted at being really liked by the Academy.

And countless Angelenos have memories of youthful jobs as Music Center ushers.

“I worked there as an usher during my senior year of high school,” recalls William Estrada, now curator and chair of the History Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “It was the days of Zubin Mehta and we were required to wear these heavy, long Nehru-type jackets that were just awful to wear in the summer. Dorothy Chandler had her own parking space, and sometimes one of us was selected to walk her from her car to her seat.”

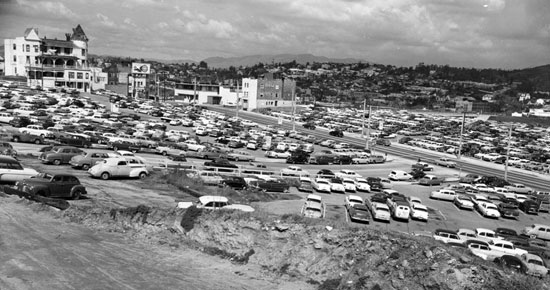

Today, Estrada notes, the Music Center, built on the site of the old Bunker Hill community, is just one cultural component in a downtown cityscape that is hardly recognizable compared to its pre-1960s, World War II incarnation. And it has expanded: The LA Phil is now housed at Disney Hall, the Center’s latest venue, and the L.A. Opera is at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

Nonetheless, some things change more than others: this week’s anniversary kickoff was sponsored by Cadillac.

Click here to buy tickets to anniversary events and to share your memories of the Music Center, and here to volunteer.

Architect Welton Becket presents plans for the new Music Center to the Board of Supervisors in 1960.

The Music Center was built as a public-nonprofit partnership on county land but was underwritten by private donations. Photo/Herald Examiner

The Mark Taper Forum went up in 1966, covered with a mural of precast terrazzo. Photo/Herald Examiner

Some memorable moments occurred during the Music Center's reign as the Oscar's home. In 1974, a streaker crashed the party and actor David Niven's presentation.

Posted 4/3/14

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink