One dream, many hands in Metropolis II

February 15, 2012

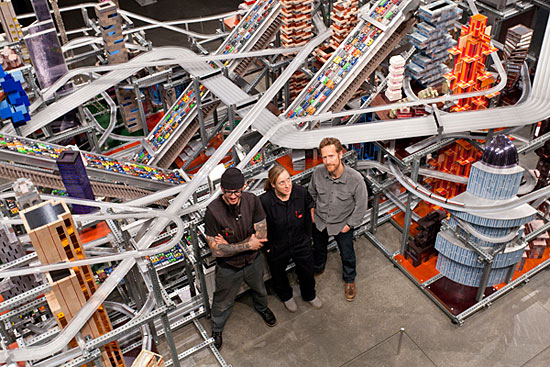

Many helped build Burden's city, including Rich Sandomeno, Alison Walker and leader Zak Cook. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Chris Burden’s vast, new miniature skyline may have been one artist’s urban vision, but behind the scenes, it took a village to build “Metropolis II”.

“It was a long process—almost five years—and it took a lot of people,” says the L.A. artist on a recent morning at LACMA, straining to be heard over the din of his creation. The idea, he says, was to evoke the energy of a modern city; around him 4,400 tiny toy wheels on 1,100 toy cars whoosh around an elaborate thicket of toy skyscrapers at up to 240 scale miles per hour.

The room-sized piece, opening to the public January 14, is on long-term loan to the museum from its owner, LACMA trustee Nicolas Berggruen. A big hit in sneak peeks last month, it will be available for viewing anytime, but will only operate Fridays through Sundays, with a special showing on the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday.

Situated just a short walk from Burden’s iconic “Urban Light,” it is mesmerizing and frenetic, a singular vision of a way of life familiar to every visitor with a car in the parking garage of the museum. But Zak Cook, Burden’s lead engineer, says as many as eight people at a time were assigned to the project, working under the artist’s watchful eye in his rural studio in Topanga.

“In all,” he says, “probably 14 people had a hand in it.”

Hiring crews of assistants isn’t unusual for successful artists, who often need extra hands and special expertise to execute large-scale ideas. “It doesn’t take away from the fact that it’s Chris’ work,” Cook notes. “The work couldn’t exist without Chris. It could exist without me.”

Burden’s crew, like the piece, reflected Southern California: There were two special-effects artists and two college-level art instructors, a maker of artisan snowboards, woodworkers, ceramicists and assorted masters of fine arts from UC Riverside and UCLA. One of the craftsmen on the prototype was the lead guitarist in the L.A.-based band “Dengue Fever.” Much of the infrastructure and train wiring was done by a heavy diesel mechanic-turned-jewelry-designer who was a finalist last year on Lifetime Television’s “Project Accessory.”

Some laid the Plexiglas track. Some built the dreamlike skyscrapers. Some installed the intricate floors and platforms. UC Riverside MFA Alison Walker and the “Project Accessory” finalist Rich Sandomeno came to know the piece so well that LACMA has since hired them to operate and maintain “Metropolis II” and act as a sort of pit crew.

“It was supposed to be a 9-month job and I ended up working on it for three years,” joked Sandomeno. “But it’s been so great to work with Chris and Zak and all the other artists. Besides, he adds: “When I was a kid, I loved Hot Wheels. “

The combination of Burden’s vision and all that painstaking labor is as intricate and playfully serious as art gets—a vast, buzzing skyline that has been compared to New York, L.A., “The Jetsons” and the 1939 World’s Fair. In the course of an hour, the tiny vehicles whip around the thicket of fanciful high-rises a collective 100,000 times on 18 lanes of traffic.

“It’s a city of the past and a city of the future,” says Burden. “It’s a city of the past in the sense that the cars run free, and a city of the future in their speed.”

An earlier, much smaller, version, with only about 80 cars, was built in 2004 for a Japanese museum, Burden says, “but they showed it for six months and then the museum changed direction. “ After the piece was put into storage—“all that work and then nobody got to see it”—Burden decided to make another Metropolis that would be “bigger and better.”

“Metropolis II,” however, took on a life of its own, says Burden: “I think we finished right around the time of Carmageddon. Every building took three or four months, which, I think you could build a tract house in that time.”

Cook served as general contractor for Burden’s architectural direction, working out such not-so-minor details as how to make the cars move reliably. (After much trial-and-error, Cook invented a sturdy, yet invisible, electrically powered conveyance system that hauls the toy cars uphill with magnets, like a rollercoaster, then releases them.)

Burden guided the team closely, Cook says, but also welcomed their input. Many contributed ideas for the exquisite buildings, which the team gave informal names: “AzDec Plaza” was a half-Aztec, half-Deco extravaganza contributed by Walker. An octagonal black high rise with blue windows, built by painter and fellow MFA Greg Kozaki, was known as “DarkTower.” A beautiful blue-and-green glass tile skyscraper was dubbed “Linkous Tower” by Frank Diettinger, a mold-maker who had done special effects for films such as “Sleepy Hollow” and “Bride of Chucky”, and who wanted to honor deceased indie singer-songwriter Mark Linkous.

“Whoever built it got to name it,” says Cook, adding that there was one major exception. “There’s an Eiffel Tower-looking building made from erector set parts, with the uppermost narrow part kind of extended, and Chris named that one.”

“Yeah,” laughs Burden, “I call it ‘Viagra Tower’ because it’s too tall.”

Cook worked on the piece from its inception. Of all the team members, he acknowledges, he probably has the least artistic resume. The 42-year-old son of a former Time correspondent, he graduated from UCLA with a degree in geography and worked for several years in the consulting division of CALSTART, a Pasadena-based clean transportation consortium.

But after a trip to India in 2000, he says, he realized that he didn’t want to keep doing white papers on the environmental impact of ports and airports; he wanted to write fiction and children’s books.

In search of a day job, he got a call one day from a friend who worked for Burden’s wife and fellow artist Nancy Rubins; Burden needed someone to help restore his 1998 sculpture “Hell Gate”, a massive bridge made of erector set pieces. The friend knew that Cook had done construction work in college.

Learning on the job, Cook then went on to help Burden build several more major pieces, including Burden’s 2001 “Bateau de Guerre”, a massive battleship made of gas canisters, and his 2002 model of a British landmark, “Tyne Bridge”.

Burden jokes that Cook “was in charge of work-ethic.”

“He’s very precise and thorough,” says the artist. “I couldn’t have done this work without somebody like him.”

Cook says that now that “Metropolis II” is finished, he intends to return to his own pursuits, and maybe finally finish those children’s stories.

“Not that Chris and I would rule out working together again in the future, but, honestly, this is such a great note to go out on,” he says, watching from a balcony at LACMA as the traffic hums by in the city that he helped make.

“I don’t see how I could ever top this.”

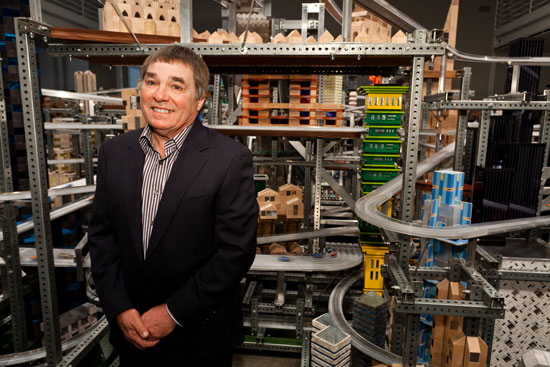

Chris Burden with his creation, created in his Topanga workshop. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Posted 1/12/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink