Patriot with a No. 5 paintbrush

April 14, 2010

Kent Twitchell casts a huge shadow in the Los Angeles public art world—literally.

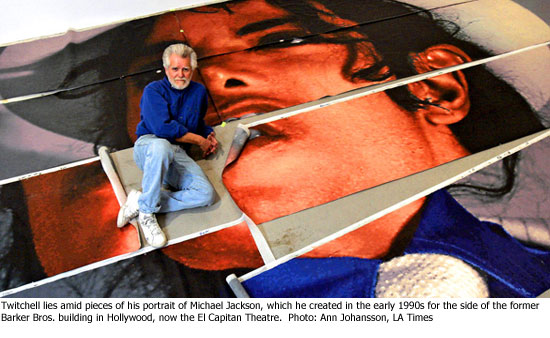

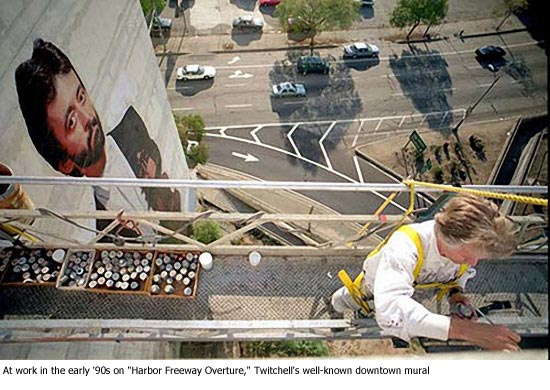

For decades, his multi-story portraits of artists, movie stars and musicians have helped define a quintessentially L.A. cityscape as big as all outdoors.

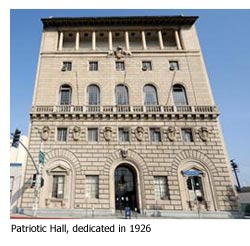

Now he’s headed someplace new—indoors—with a task ahead of him that looms as large as ever: bringing back to life the essence of murals that vanished decades ago in the Bob Hope Patriotic Hall.

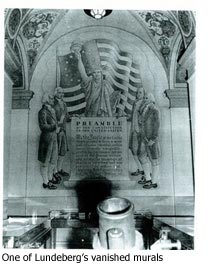

The scenes, created by Chicago-born artist Helen Lundeberg, mysteriously disappeared sometime in the ‘70s—stripped off the walls and destroyed or spirited away to points unknown.

Now the landmark 1926 building, once the county’s Hall of Records, is getting a $45.4 million renovation. As part of the project, Twitchell has come onboard to recreate and reimagine the three murals that once dominated the lobby of the building, now home to the county’s Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

In an interview this week at his downtown studio, Twitchell discussed for the first time how he plans to approach the job. He says he intends to respect the vision Lundeberg created in 1942, while drawing on his own unique sense of aesthetics, with influences ranging from Mt. Rushmore and the Statue of Liberty to Norman Rockwell and the famous faces of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

“I happen to be a patriot,” he says. “Here’s a chance for me to be doing something I really believe in.”

Twitchell, who enlisted in the military right out of high school and went on to become an Air Force illustrator stationed in London, has an idea about the people he’ll depict in his Patriotic Hall scenes. He proposes making every figure in the murals a veteran—from character actor William Sanderson (“Newhart,” “Deadwood,” “True Blood”) to Twitchell’s octogenarian Uncle Paul. He’s also poring over WWII-era books of Hollywood luminaries to discover which ones might qualify for a cameo appearance in one of the murals. “Clark Gable flew suicide missions as a fighter pilot,” he says.

Twitchell muses about the juxtaposition of faces he envisions for the murals—“a superstar, a character actor, someone you don’t know.”

“I want to make it uniquely Los Angeles,” he says. “These are our people. That is Los Angeles.”

Patriotic Hall, seen by millions zipping through the intersection of the 110 and 10 freeways, is set to reopen in mid-2012. It seems particularly well-suited for a Twitchell project—and not just because it’s located just a short stroll from the artist’s current studio.

Patriotic Hall, seen by millions zipping through the intersection of the 110 and 10 freeways, is set to reopen in mid-2012. It seems particularly well-suited for a Twitchell project—and not just because it’s located just a short stroll from the artist’s current studio.

Like one of Twitchell’s outsize portraits, the building “becomes part of your L.A. urban landscape psyche,” says Letitia Ivins of the county’s Civic Art program, who is serving as project manager for the Patriots Hall work.

She said the committee that selected Twitchell from a field of about 30 other applicants was moved by his track record, personality and obvious passion for the project.

“His sincerity simply won over the committee,” she says. “He is in love with this project and wants to leave a legacy not only for his heirs but also for Los Angeles.”

His final proposal for the $285,000 mural project is still under wraps until the contract is signed, but Twitchell says he expects to follow the original composition of Lundeberg’s works, “Preamble to the Constitution,” “Free Assembly” and “Free Ballot.” Each of the approximately 20-feet-by-12-feet murals—viewable now only in old photos—was hand painted in oils, with funding from the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, which was winding down after the country’s entry into World War II.

“When I found these things online, I thought: why should I do something different?” Twitchell says. “Especially when her work was so unceremoniously and capriciously taken away.”

And that’s something Twitchell can relate to.

A number of his own works have been obliterated over the years, including the six-story high “Ed Ruscha Monument,” which was painted over by work crews in 2006. A $1.1 million settlement—partly paid by the federal government, which owned the building on Hill Street—was hailed as a victory for artists’ rights.

Twitchell describes himself as a reluctant litigant.

“It was almost like if I didn’t, public art would have taken a hit,” he says. “I was put in a corner. I had to fight.”

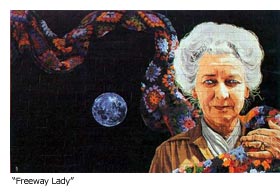

Gone, too, is “Freeway Lady,” the grandmother draped with a colorful afghan, though Twitchell plans to repaint and install her on the campus of L.A. Valley College after the Patriotic Hall work is completed. He’s also finishing up a painting of John F. Kennedy for an upcoming show at the Vincent Price Gallery at East L.A. College, where Twitchell was a student, along with Cal State L.A. and what is now the Otis College of Art and Design. The JFK portrait is an offshoot of a Berlin Wall installation that Twitchell created for the Wende Museum of the Cold War.

“I love public art, and have ever since the hippie days in London,” says Twitchell, 67. “L.A. just seemed like the perfect place for it in the ‘60s.”

Twitchell’s Flickr photostream provides a vivid look at his work, past and present. (Amazingly, given the scale of his pieces, his tool of choice for applying acrylic emulsion is generally a No. 5 or No. 6 watercolor brush.)

Twitchell, who moved to L.A. in 1966 after a stopover in Atlanta following his London tour of duty, currently lives in Hollywood. He bemoans the incivility of modern-day street life in the city, and doubts he could have created the same body of work if he was starting out today. City restrictions on building signage are an understandable response to visual pollution, he says—“L.A.’s starting to look like ‘Blade Runner,’ ”—but they also make large scale outdoor art a virtual impossibility.

Then there are the taggers—gang-affiliated and wannabes—who routinely disfigure public artwork.

“Doing things outside is enemy territory now,” he says. “It’s foolhardy.”

He laments “the destruction of so many pieces that I put my heart and soul in,” and says: “What they’re doing is by definition barbaric. It takes months to create and minutes to destroy.”

Working indoors on the Patriotic Hall project will provide a lasting refuge for his art. He said he has shied away from government commissions in the past—“I’ve always refused to compete with other artists”—but decided that this one was worth going for.

Working indoors on the Patriotic Hall project will provide a lasting refuge for his art. He said he has shied away from government commissions in the past—“I’ve always refused to compete with other artists”—but decided that this one was worth going for.

“It just seemed like this was a chance,” he says, “to do a very, very unique piece.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink