Rehab time for another Hollywood star

May 5, 2010

The Ford Amphitheatre, long in the shadow of its glamorous sibling, the Hollywood Bowl, is gearing up for its own big moment.

And like the under-appreciated secretary who finally whips off her glasses in Act III, the Ford has been keeping its charms under wraps for a good long time.

“We don’t want to be the Hollywood Bowl,” says Adam Davis, the Ford’s managing director, speaking with pride of the showcase that his more intimate venue provides for a diverse range of Los Angeles County performing artists.

But “people need to see it. People need to know it’s here.”

Boosting the Ford’s visibility—and fixing its long-running travails with “stacked” parking—are at the top of the agenda as the county owned-and-operated institution gets to work this week on its first ever master plan.

Also on the Ford’s wish list for the master plan: building new rehearsal and office space, along with a year-round restaurant; expanding or upgrading the 1,200-seat amphitheatre and its companion 87-seat theater, [Inside] the Ford; creating a sound barrier so that both venues can host performances simultaneously, and incorporating new environmentally-friendly technology throughout the site.

Also on the Ford’s wish list for the master plan: building new rehearsal and office space, along with a year-round restaurant; expanding or upgrading the 1,200-seat amphitheatre and its companion 87-seat theater, [Inside] the Ford; creating a sound barrier so that both venues can host performances simultaneously, and incorporating new environmentally-friendly technology throughout the site.

Levin & Associates Architects, which has worked on renovating and redefining a number of Los Angeles’ highest profile landmarks—including the Griffith Observatory and the Bradbury Building—has been selected to develop the master plan. The first big meeting on the project is scheduled for Thursday, with a goal of completing the plan by the end of the year. The planning is being funded by a $350,000 grant from the office of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. The overall budget for rehabbing and rethinking the Ford will depend on what the master plan comes up with.

The master plan project is getting underway as the Ford turns 90 this year. Or to put that in Hollywood terms: it was time for a little work.

The master plan project is getting underway as the Ford turns 90 this year. Or to put that in Hollywood terms: it was time for a little work.

“It’s a pretty magical place when you walk into it,” Davis says. But he yearns for a “point of entrance, a point of arrival” for the Cahuenga Boulevard amphitheatre site, located just a short hop across the 101 Freeway from the internationally famous Bowl.

Davis is exaggerating—but only a little—when he says: “If I had a nickel for every person who told me ‘I never knew this place existed, and I’ve lived here all my life,’ I could have funded the master plan.”

An LED sign for the Ford was installed on Cahuenga last year.

But “it’s still a hidden gem,” says Arts Commission Executive Director Laura Zucker who, with then-Supervisor Ed Edelman, helped build the modern-day Ford into a local arts institution in the early 1990s. “If you know, you know. If you don’t know, you can’t see it from the road.”

But “it’s still a hidden gem,” says Arts Commission Executive Director Laura Zucker who, with then-Supervisor Ed Edelman, helped build the modern-day Ford into a local arts institution in the early 1990s. “If you know, you know. If you don’t know, you can’t see it from the road.”

As it stands now, even people who can find the venue turn in and find themselves immediately facing “a parking lot and a blue motel,” Davis says. (The ‘60s-era one-time motel now provides office space for Davis and other members of the Ford staff, as well as for employees of the L.A. Philharmonic.)

The master plan aims to build on a series of improvements the county has undertaken at the Ford since 1999. Those improvements, totaling more than $6 million, include a $1.2 million electrical renovation; new signage and sound consoles; remodeling the box office, concession area and restrooms; and adding new picnic plazas, an ADA-compliant pathway and an elevator to make the steep terrain accessible to more people.

The master plan effort takes a longer, broader view of the facility. “It’s gotten to the point where we can’t piecemeal it anymore,” Davis says. “I’m so grateful that the county wants to invest in the place. It’s now important to plan not just for the next summer but for the next 30 years, 40 years.”

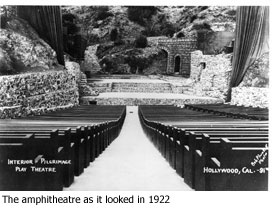

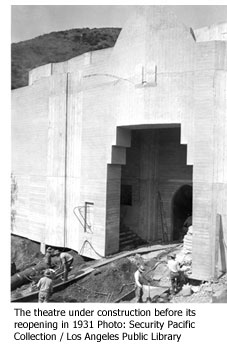

It was 90 years ago that the first theater on the Cahuenga Pass site was built by heiress and landowner Christine Wetherill Stevenson. Stevenson, who also led a group that acquired the property the Hollywood Bowl now sits on, created the venue as a setting for her “Pilgrimage Play”—a pageant she wrote about the life of Jesus. Stevenson’s production was “a highly attended event throughout the 1920s,” according to an art commission history of the locale, which notes that after the original theater burned down in a 1929 brush fire, the community rallied to rebuild it in its current form in 1931.

The land was deeded to the county in 1941, and the “Pilgrimage Play” was performed there until 1964, when factors that included a legal challenge to staging a religious show on county property shut down the production, according to another arts commission history of the site.

The setting is now a county regional park and the amphitheatre bears the name of the late County Supervisor John Anson Ford, an early proponent of fixing up the dilapidated facility. The launch of “Summer Nights at the Ford” in 1993 inaugurated the facility’s modern era as a venue for an eclectic mix of locally-based entertainment ranging from dance and music to theater and film. (This year’s summer schedule is here.)

“The theater’s been around since the 1920s, but we’ve only been programming it for 17 years,” Davis says. In that sense, he says, “we are a teenager.” And the master plan’s goal, in part, is to help the Ford answer the question, “What do we want to be when we grow up?”

Posted 5-05-10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink