“The Rock” set to roll through L.A.

August 15, 2011

Later this summer, a 340-ton boulder will make its way from the Inland Empire to the middle of Los Angeles.

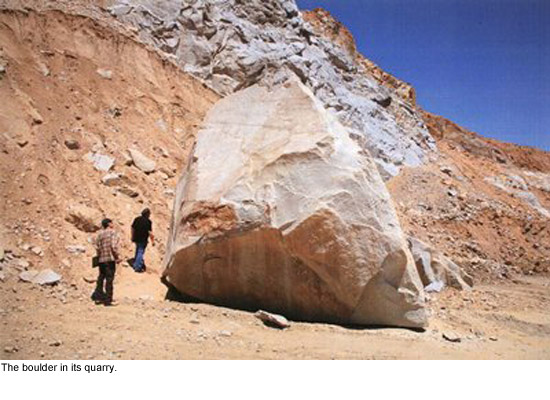

Recumbent on steel beams and a specialized 208-wheeled transporter, it will travel by night as the basin lies sleeping, a rough mass of California granite 21 feet wide and two stories tall. It will move on surface streets because it is too slow and huge for the freeway. At each dawn, it will halt; its entire 72-mile trip will take place at less than 10 mph.

From one end of the Southland to the other it will make its epic 9-day journey: down dark frontage roads beside the Pomona Freeway, past the twinkling lights of Ontario International Airport, along strip-malled boulevards in Diamond Bar and Walnut, through porch-lit subdivisions in Whittier and La Palma. Preliminary route maps take it past fast food joints in Compton, startling the night shift, and up through South L.A. by starlight, taking in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the stately palms of the West Adams District.

Finally, The Rock, as its guardians have come to call it, will turn on Wilshire Boulevard, lit by the city and flanked by office buildings, and jog north on Fairfax Avenue for just a short distance. There, at last, it will find its elegant new setting—poised over a 456-foot-long, 15-foot-deep concrete trench as part of Michael Heizer’s Levitated/Slot Mass, an internationally anticipated installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“It’s not like anything we’ve ever done,” says LACMA’s associate vice president for special art installation, John Bowsher, who is overseeing the boulder’s odyssey.

The artwork, scheduled to open to the public in November, will allow visitors to walk underneath the massive granite formation, down a slope that will create the illusion that the boulder is levitating. Assembled, the piece will be about as tall as the Resnick Pavilion, its neighbor on the LACMA campus.

But if Heizer’s work is expected to be a tour de force, so is its installation. LACMA director Michael Govan has called The Rock “one of the largest monolithic objects moved since ancient times.”

Orchestrating the rock’s move to LACMA from a Glen Avon quarry will be Emmert International, a Portland, Ore.,-based heavy-haul transporter.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Albrecht says a 15-man crew will accompany the boulder throughout the journey, along with various LACMA officials and police escorts. Though a tentative route has been mapped out, he says, the company is still in the process of acquiring state and local permits.

So far, the boulder is expected to travel uncovered (“No plans to shrink-wrap it, or anything like that,” he says, laughing). But like the route and the planned August 5 departure date, that could change as the deadline approaches. LACMA’s Bowsher says there’s been talk of boxing or partially covering the boulder because the artist is concerned that the spectacle of a 21½-foot-high hunk of granite riding like the Rose Queen through the streets of Los Angeles County will detract from the totality of the sculpture.

Heizer, who is famously private, could not be reached for comment. But Albrecht says the artist “has been involved for the whole process,” cautioning them via LACMA to “make sure the rock isn’t scratched or etched, make sure it’s carefully handled, make sure you don’t leave any big marks on it.”

Damaging it would seem to be the least of anyone’s worries, considering that the boulder was blasted in 2005 from the face of a quarry in the Jurupa Mountains and survived intact.

“Came right from the crown of the mountain,” marveled Dan Johnston, then-project manager for Paul J. Hubbs Construction, which owned the quarry. “Blast brought it down and it landed right in the middle of soft dirt.”

Johnston, now retired, says that as soon as he saw it he called Heizer, a geologist’s grandson known for massively scaled artworks, including Double Negative, a 1,500-foot trench cut into the side of a desert mesa.

“Michael had bought some large rocks from us before, in 2004 and 2005, for other projects,” Johnston says. “He wanted granite, and the thing about granite is that not a whole lot of places have it. Riverside granite is like Portland cement—if you know about rock, it’s something you look for. And he had come to us looking for large rocks.

“Well, that was one good-lookin’ rock…Way it was shaped, I knew he’d love it. And he did, he fell in love.”

Stephen Vander Hart, co-owner of Stone Valley Materials Inc., which now owns the quarry, says he had heard that the artist paid $120,000 for the boulder. But Johnston, while refusing to divulge the actual price, says “it was nowhere near that much.”

Vander Hart says the quarry’s crews had been working around the rock for years when his company took over in 2010, and its safekeeping was a condition of the buyout.

“We’ve had to work hard to not bump into it,” he says. “Most of the guys here are just regular equipment operators, blue collar guys, love their wife and kids, and they’re just like, ‘Get it the hell outta here, let me do my job. They’re not that into art.”

But the quarry boss says he, for one, was touched when he heard LACMA Director Govan talk about the artwork and how it came to be.

“He talked about how 400 years from now, people would ask, ‘How did this group of people move something this size? What was their motivation?’ California is all strip malls and franchises. Everything is brand new, at least here in the Inland Empire. We bury our history. But this is something that will be there for a long, long time.”

Posted 6/29/11

Updated 8/16/11: The groundwork is taking a little bit longer than expected, but officials at LACMA say the rock is expected to roll shortly after Labor Day.

“There were some permitting issues for the route from the quarry, ” says Miranda Carroll, LACMA’s director of communications. The tentative start date now is September 6, with an arrival at the museum on September 14 or 15, she says.

The 340-ton boulder is a key element in a much-anticipated installation by the reclusive earth-art master Michael Heizer. Museum officials had hoped to move the 340-ton boulder from its Riverside-area quarry this month.

In any case, Carroll added, “there won’t be a big hoo-hah because we’ll be moving it in the middle of the night.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink