A legend lives on, with library’s help

March 21, 2013

Heavy metal: the suit John Barrymore wore in "Richard III" is just one of the Anthony Quinn Collection's treasures.

There’s the suit of armor his mentor, John Barrymore, gave him. There’s the cap, now bronzed, that he wore in “Zorba the Greek.”

When Anthony Quinn left his papers to the East L.A. library on the site of the house where he spent part of his boyhood, the late actor defined the bequest broadly; there are movie stills, letters, handbills, art works, even a couple of Oscar nominations.

Less comprehensive was the plan to preserve the collection for posterity.

“Most of this came to us in boxes, which we changed to County Library boxes,” says Chicano Resource Center Librarian Daniel Hernandez, who oversees the Anthony Quinn Collection, a trove of some 2,000 items of personal and show business memorabilia that the artist gave to the county library more than 25 years ago.

The collection is a historical gem, offering a wide-ranging view of Quinn’s East Los Angeles roots and his life as a self-made man and 20th century film star, but its preservation has been a concern since Quinn made the donation in 1987, says Hernandez.

A few pieces—the suit of armor, the Zorba cap—have been used as library displays and a few others have been loaned to other museums for exhibits on show business or Latin culture. Most, however, have spent the past couple of decades in storage, he says, and the cardboard library boxes, while an improvement over the original containers, have hardly been a long-term solution.

“Everything has been safe,” says Hernandez, gesturing to a wall of cabinets, stacked floor to ceiling, in a locked room at the Anthony Quinn Library. “But even though it’s OK for right now, it’s not OK for the future to come.”

So this week, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors accepted a $6,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help preserve the cache, from film scripts and taped interviews to thank you notes and birthday cards. The funding will, among other things, underwrite an assessment from a professional conservator and pay for appropriate preservation supplies and containers.

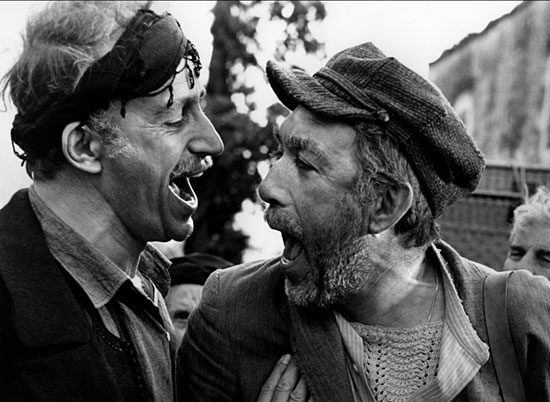

“There’s not that much knowledge of this collection,” says Hernandez, flipping through a draft of one of Quinn’s two autobiographies, typed and annotated on fragile onionskin paper. Next to it sat a cardboard box filled with gilt-framed black-and-white photos—Quinn as a young actor, Quinn in Italy, Quinn with his “Zorba” co-star Melina Mercouri.

“People are aware it’s out there but they don’t know what’s in it. One of our goals is to get that out into the public consciousness.”

Born in 1915 in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, Quinn—who inherited his surname from his part-Irish father, Francisco—came into the U.S. as an infant with his parents, who were migrant farm workers for several years before settling in Los Angeles. Here, Quinn’s father found work as a studio property man and the family moved into a house at the corner of Hazard and Brooklyn (now Cesar Chavez) avenues in East Los Angeles.

“I can’t tell you what an emotional thing it is to be standing on the spot my cousin beat the hell out of me,” Quinn joked to the Los Angeles Times in 1983, when the site—long since razed to make way for the county’s Belvedere Library—was renamed in his honor. In a more somber moment, the actor also said that when he was 9, his father had been killed in an automobile accident near the same corner.

Photos in the collection commemorate Quinn’s youth as a student at Belvedere Junior High School and Polytechnic High School, where he took courses in art and architecture, but, according to obituaries, never earned a degree.

After stints in Los Angeles as a boxer, a musician and even an evangelical preacher, Quinn tried acting. In 1936, he debuted in a cameo role in the film “Parole” and in a stage role that had been written for John Barrymore, a much older and more famous actor.

Among the papers in the collection is an account of his friendship with Barrymore, who took him on as a protégé after seeing the performance, and later gave him a suit of armor he had worn in Richard III, comparing it to the sword a retiring bullfighter hands down to “his preferred novillero.”

The suit—the largest item in the collection—is on display in the reading room of the branch library that now stands on the site of Quinn’s old homestead.

Quinn went on to act in more than 100 movies, working well into his 80s and winning two Oscars for best supporting actor—first as the brother of the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata in “Viva Zapata!” and later as the artist Paul Gauguin in “Lust for Life”.

As his fame grew, he spent more of his time in Italy and New York than on the West Coast, but he maintained his local connections.

“He never forgot his people,” the sister of one of the defendants in the famous 1942 “Zoot Suit” murder trial told the Los Angeles Times at the 1983 library dedication, noting that Quinn—married by the time of the historic trial to the director C.B. DeMille’s daughter—had gone out on a limb both politically and professionally to help raise money for the appeal.

“He’s still pretty much of a local hero,” says Hernandez. “He’s an example of how you can work your way up and always care for your community. People here all seem to remember his aunt, or to have gone to school with him, so it’s a big social goal for us to save his works and preserve them.”

Quinn died in a Boston hospital in 2001 of respiratory failure. “But here in the community,” Hernandez says, “he’s very alive.”

Quinn won two best supporting actor Oscars, and was nominated for his star turn in "Zorba the Greek."

Posted 3/21/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink