Fault findings break new ground

October 21, 2011

Years before the first trains roll, the Westside Subway is already getting somewhere—at least when it comes to seismic discoveries.

Years before the first trains roll, the Westside Subway is already getting somewhere—at least when it comes to seismic discoveries.

Earthquake geologist James Dolan, a USC earth sciences professor and consultant to the transit project, this week presented findings that pinpoint the location—and active seismic status—of a formation known as the West Beverly Hills Lineament.

Remember that name.

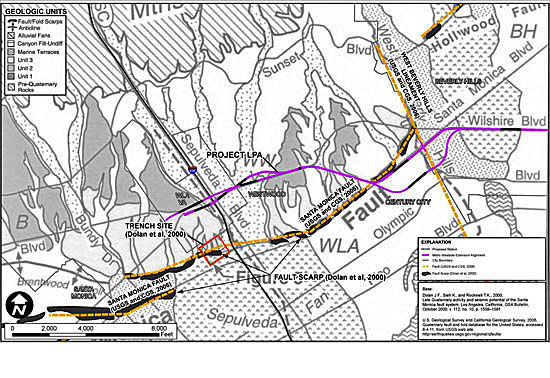

It turns out the WBHL, as it’s known, is a branch of the mighty Newport-Inglewood Fault, an active and powerful system stretching from Culver City to Newport Beach and continuing south through San Diego and into Mexico’s Baja peninsula.

Dolan led the research team that first came across the formation and named it in the early 1990s. But it was only in recent months that intensive research to determine the safest site for the subway’s Century City station helped the geologist “confirm our earlier inferences that the West Beverly Hills Lineament is the northernmost part of the Newport-Inglewood Fault System.”

In the world of seismology, that’s a big deal. The Newport-Inglewood system is a giant and has been active during the Holocene era (i.e., the last 11,000 years), most notably in 1933, when it caused an earthquake in Long Beach that killed some 120 people, making it the second deadliest in California history, after the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

The presence of the WBHL and the nearby Santa Monica fault, which is also active, make it too dangerous to build a Santa Monica Boulevardstation for the new subway in Century City, Dolan and other scientists told a Metro committee Wednesday. They said that another proposed location for the station—at Constellation Boulevard and Avenue of the Stars—was a better option because it showed no evidence of earthquake faults.

The state has recognized the WBHL and the Santa Monica Fault as active fault zones on its maps, Dolan said, but does not yet classify them as such under the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act, which imposes building restrictions in such areas. Data like those acquired during the recent research are the kind of information needed to eventually place such active fault zones under Alquist-Priolo regulations, Dolan said.

“As a scientist, it’s very exciting,” said Lucy Jones of the U.S. Geologic Survey and Caltech, who reviewed the research as part of an independent review panel. “Knowing that the Newport-Inglewood Fault is active this far north is new,” she said, later adding that the finding is “of significant import for the city of Los Angeles.”

The WBHL extends north-northwest from Culver City through West L.A., bisecting west Beverly Hills and east Century City, traversing Constellation andSanta Monica boulevards between Moreno Drive and Century Park East before ending roughly at Sunset Boulevard.

A “major event” on the WBHL could mean an earthquake ranging in magnitude from 6.4 to 7.2, along with ground movement of three to six feet, according to an executive summary of the experts’ findings.

While it’s not possible to predict when a given fault might slip, it’s prudent to take the potential impact seriously, Dolan told the committee:

“Earthquakes don’t typically recur on our kind of human lifetime scales,” Dolan said. “That doesn’t mean that we can disregard the risk associated with these things. It very well may be it will be 3,000 years until we have an earthquake on the Santa Monica Fault. Then again, it could happen tomorrow. It depends on whether you’re a betting person, I guess.”

While acknowledging that such discoveries can spark concerns, Dolan said in an interview that he prefers to take an all-news-is-good-news approach.

“I think anything we learn about active faults in L.A.is always good news,” he said, “because it’s absolutely critical that we fully understand the seismic threat facing us as residents of earthquake country.”

Members of the Metro committee listened attentively during Dolan’s presentation (and one, Richard Katz, asked him to slow down at one point so he could take in the rush of information.)

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, another committee member, said he was so engrossed with Dolan’s style of scientific explanation that it might once have set him on a different career path.

“If I’d first met him 40 years ago, I would have been a geology major,” Yaroslavsky said.

Dolan, an expert on urban faults and the seismic hazards underlying the metropolitan Los Angelesarea, said the latest round of extensive research gave him a chance to catch up with his unfinished business with the WBHL. “These data have been a wonderful validation of our earlier research,” he said. “They’ve greatly fleshed out the details of these faults. Those details are the critical information we need.”

At the committee meeting, he spoke enthusiastically about the exhaustive testing that helped unearth those details, including “cone pentetrometer” tests and “seismic reflection profiles” (“It’s like a CAT scan of the earth,” Dolan explained to the committee.)

After it was all over, the committee chair, Diane DuBois, paid Dolan and the other scientific experts the ultimate layperson’s compliment on their presentation:

“I even understood it,” she said.

Posted 10/20/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink