Testing for toxics at the Marina

March 18, 2010

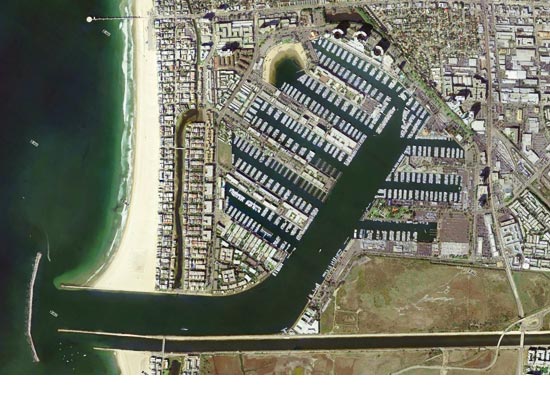

It’s the largest man-made small-boat harbor in the United States—and it’s about to see the launch of a new project to measure toxic pollution.

The harbor at Marina del Rey is home to over 4,000 motor craft and sailboats. Built on former wetlands at the mouth of Ballona Creek by the Army Corps of Engineers, the Marina opened in the summer of 1965.

Hotels, condos, parks and restaurants sprang up around the giant marina on county unincorporated land. Beyond the Chris-Crafts and cruising yawls, the marina boasts a sandy “Mother’s Beach” that’s a favorite for wading and swimming because it’s protected from the ocean’s waves.

But the marina also has a history of elevated levels of five toxic substances, landing the man-made harbor on a list of “impaired” waterways under the federal Clean Water Act, along with thousands of polluted lakes, rivers, harbors and estuaries around the nation.

As a key preliminary step to a cleanup, the Board of Supervisors approved a plan this week to team up with the City of Los Angeles and Culver City to pay for a three-year, $4.5 million monitoring regimen for the toxics in waters and sediments of the harbor and in the storm water drains that flow into the marina.

“The first three years we’ll develop a baseline to find out what the levels [of the pollutants] are currently,” said Oliver Galang, a senior civil engineer at the Department of Public Works, who will head up the toxics monitoring project.

Galang’s team will then guide the formation of a cleanup plan for any toxics that remain unacceptably high. The aim is to bring all inflows of the toxics under acceptable levels for swimming and other recreational uses by 2016.

By July, Galang hopes to get monitoring underway in the man-made 2.9 square mile watershed that includes the Marina, parts of Venice and a small slice of Culver City.

Three of the toxics found in elevated levels are metals: copper, lead and zinc. Galang says that they come largely from automobile brake pads that shed minute amounts of copper and zinc onto the streets, where they are flushed into the storm drains and into the water. The lead sources may range from discarded industrial supplies, batteries or residues washed from old lead-based paint, he says.

Also to be measured are two long-banned organic compounds found in harbor sediments in the 1990s. Chlordane was a pesticide sold until the early 1980s; PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, were found in paints, plastics and electrical equipment until 1979.

Past monitoring showed that the bulk of the toxics sat in mucky sediments at the harbor’s bottom, not suspended in the water itself. County health officials say they can’t make a definitive statement on the presence of the toxics and any potential health issues without further data.

Once underway, data technicians will take monthly water samples in the harbor and in the storm drains as well as analyze chemicals in sediments beneath the harbor. Divers will capture fish and mussels to check for buildup of toxics in the animals’ tissue. They’ll also gather and analyze water during winter storms.

Most of the toxic pollutants found in the past lurked in the sediments of the back basin, the inland edge of the harbor.

“The back basin doesn’t have a lot of water circulation,” Galang said “The tide doesn’t flush it out very well.”

The toxics plan is the second pollution fix to be undertaken at the harbor. An earlier plan aims to cut levels of harmful bacteria, but it ran into trouble when state regulators reported last month that bacterial counts exceeded limits 186 times between 2007 and 2009.

In February, the state’s Regional Water Quality Control Board staff proposed levying nearly $275,000 in civil administrative fines against the county’s Flood Control District, which built diversions to carry water to sewage treatment. In its complaint, the state held that the district alone was responsible for the high bacteria counts—but not the city of L.A., where the dirty water originated.

Public Works officials have called the proposed fines “irresponsible and counterproductive” and asked the state to “rethink” them. The full Regional Water Quality Control Board will consider the fines at their May meeting.

The county Department of Public Health closely monitors the presence of harmful bacteria in the waters. Public warnings about bacterial counts were reduced significantly when the county recently installed underwater propellers to improve circulation along the marina beachfront, said Beaches and Harbors Department Director Santos Kreimann.

On the toxics plan, the county’s Galang said the upcoming measurements will help water specialists to fashion solutions that the county and its partners will present to the state regulators next spring.

3/18/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink