Big wheel turning

August 8, 2012

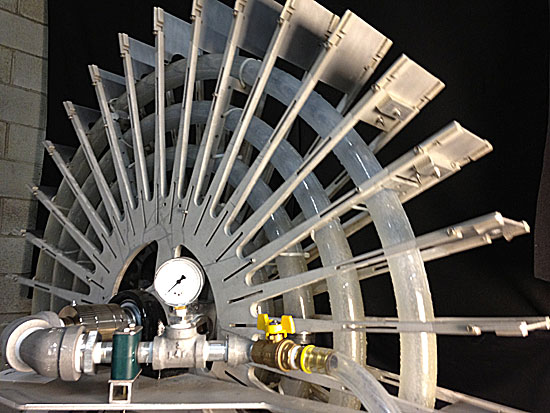

The water wheel, shown above in early prototype, would reconnect L.A. to its river and irrigate the state park.

Lauren Bon planted green rows of corn on a once-forsaken brown field in downtown Los Angeles. She enlisted military veterans to help her cultivate strawberries hydroponically on the V.A. grounds in West L.A. And now she’s preparing to make another big statement—in the form of a massive, working water wheel intended to reconnect Los Angeles with its river, its history and its current environmental realities.

The water wheel is the central element in an ambitious artwork/environmental project to be created next year on a sliver of land beside the Broadway bridge over the L.A. River. The site is right next to the Los Angeles State Historic Park at the edge of Chinatown, where Bon’s “Not a Cornfield” transformed the landscape in 2005.

Drawing on the historic water wheels that dotted Los Angeles from 1854 to 1900, this latest endeavor is being timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the Los Angeles Aqueduct—November 5, 2013. The project seems destined to spur new discussion of the landmark moment in Los Angeles history when William Mulholland first watched Owens Valley water transported along the 233-mile aqueduct gush into the San Fernando Valley and famously declared, “There it is. Take it.”

While the aqueduct’s legacy has been seen variously—and often simultaneously—as an environmental tragedy, a monumental rip-off and an essential step in enabling the growth that created modern day Los Angeles, the water wheel project seeks less to judge than to inspire fresh thinking about the future.

“I think it’s really critical for us to take a pause and think about our definition of the city,” Bon says. “My position is that it’s time to look at the next hundred years. This work is about saying we need to do a lot better very quickly with figuring out two things: how to retain our water and how to send the rest of it out to sea cleaner.”

Indeed, the water wheel—to be known by its Spanish name, “LA Noria”—is expected to play a hard-working role that goes well beyond its aesthetics. Powered by the flow of the L.A. River, the turning wheel would lift river water in buckets high above the ground. The lifted water would be filtered, transported via a flume or pipe and used to irrigate the 32-acre state park while the rest rejoins the river on its way to the ocean. The project team estimates the wheel could provide 28 million gallons a year for park irrigation, potentially a $100,000-plus annual savings.

Mark Hanna, an engineer with Geosyntec Consultants who is working on the project, says the river, with 80 cubic feet of water per second flowing through “at the lowest point in the driest season,” is perfectly capable of powering the wheel.

The project to build the 60-foot wheel, with 30 feet visible above ground, is being developed and designed by Bon and her Metabolic Studio, a philanthropic endeavor of the Annenberg Foundation, of which she is a vice president and director. Exact costs aren’t yet known but are expected to reach several million dollars by the time the project is finished.

Building the wheel is one challenge. Navigating the complex maze of official permissions needed to make it a reality is another.

The public affairs lobbying firm Kindel Gagan has been hired to obtain the approvals and permits, and the firm’s Michael Gagan says he’s encouraged by initial meetings with the vast array of agencies involved.

They include the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which owns the land, and the county Department of Public Health, which must issue a permit allowing use of the river water for irrigation. No fewer than four city departments also must sign off on different aspects of the plan—Water and Power, Planning, Building and Safety and the Bureau of Engineering—along with the state parks department, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the county Flood Control District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Metrolink, whose trains run right past the site regularly, also is an interested party.

The Los Angeles River Cooperation Committee, a joint city-county working group that evaluates upcoming river projects, gave the water wheel its blessing at its July 9 meeting. “We think it’s super-exciting,” said Carol Armstrong, who heads the L.A. River Project Office of the city Bureau of Engineering.

At the moment, the clock is ticking—literally—inside the studio, where an electronic red countdown sign marks off the time remaining until the aqueduct’s 100th anniversary.

Still, Bon doesn’t doubt for a minute that her project will be able to beat the clock.

“It’s gonna happen,” she says.

A community activist shared this model depicting the neighborhood's original water wheel as it might have looked in the 1850s.

Bon, who always likes to introduce what she calls a “device of wonder” into her projects, including “Strawberry Flag” at the V.A. and “Not a Cornfield” in the State Historic Park, sees the water wheel as a natural extension of that work. “These aren’t just surprising little projects that are popping up,” she says. The water wheel is “part of three signature projects that all share a definition of the city.”

The wheel also relates to another project currently underway called “Silver and Water.” That expansive, multimedia work-in-progress aims to tell the story about how the “alchemy of photography and Hollywood,” fueled by silver mined in the Inyo ranges and water from the Eastern Sierra, helped create the movies—and Los Angeles itself. One of the project’s elements is a traveling “liminal camera”—basically a massive pinhole camera capable of taking huge photographs—that has been built in a reclaimed container on a flatbed truck.

On a recent day, the liminal camera, which Bon dubs “the largest pocket instamatic camera in the world,” was parked outside the studio, close to where the water wheel would be built.

Inside, another machine, in the form of a working, aluminum prototype of the proposed water wheel, stands ready to make a public debut this week. While the model doesn’t show exactly how the water wheel will function in its final incarnation, it will be Exhibit A at a community open house on Thursday, August 9. The gathering runs from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at Metabolic Studio, 1745 N. Spring St., Los Angeles, with the parking and entrance located off Baker Street.

Even before the open house, Solano Canyon resident Alicia Brown said awareness of the water wheel project is building in the area. “Most of my neighbors, they know. Some have taken it lightly; others are amazed,” says Brown, who’s lived in the neighborhood since 1939.

Brown dropped by Bon’s studio recently with her own tabletop model of the historic water wheel that in the 1850s served her community, not far from where Bon’s project is to be installed. An architecture student built the model and gave it to her years ago; now she thinks it could help inspire the new incarnation. Although it’s likely that the new water wheel will be made of metal, Brown is holding out hope for wood, to more closely replicate the original.

“I’ve always loved this neighborhood so much,” says Brown, a neighborhood activist and history buff who for years has been fascinated by Solano Canyon’s vanished water wheel. “There was one there, and people should know.”

Artist Lauren Bon with Metabolic Studio's "liminal camera," near the site of the proposed water wheel installation.

Posted 8/8/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink