Embracing the dark side in rural L.A.

January 24, 2012

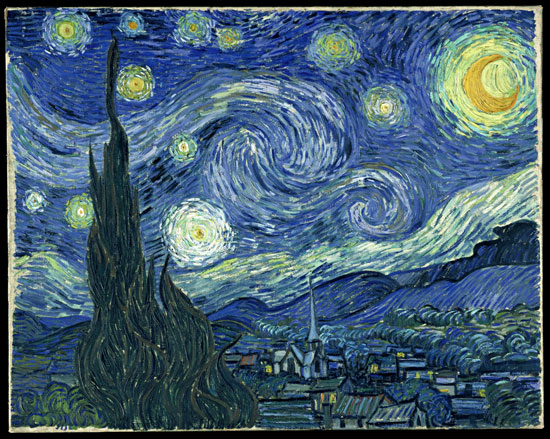

The county's new "dark skies" law may not lead to this kind of view, but it's certainly a step forward.

“Light blight.”

That’s Kim Lamorie’s term for the spectacle that occurs every time an urbanite moves to one of the rural communities near her Calabasas home. The sun sets, the black night settles over the Santa Monica Mountains, and before long, “their houses and yards are massively lit up like crazy,” says Lamorie, president of the Las Virgenes Homeowners Federation.

“It’s how you can tell when somebody’s new to the rural area.”

Eventually, she says, the newcomers come to realize that they don’t need all that security lighting and that bright lights confuse and even threaten the nocturnal animals that share their wilderness. But in the meantime, she says, all that fear of the dark can ruin one of the best aspects of mountain living:

“I can step outside my door at night,” she says, “and see the stars.”

On Tuesday, after more than a year of preparation, the Board of Supervisors restricted outdoor lights in rural Los Angeles County in an attempt to curb light pollution in such unincorporated areas as the Antelope and Santa Clarita valleys and the Santa Monica Mountains.

The new regulations create a Rural Outdoor Lighting District that encompasses those and other sparsely populated parts of the county and requires that lights on barns, corrals, ball fields and other such facilities be shielded so that they face downward, not outward and upward. It also requires outdoor lights, such as those on patios, be subdued enough so that they don’t “trespass” onto neighboring properties.

Although a handful of public safety facilities, such as those operated by the Sheriff and Probation departments, will be exempt from the restrictions, most rural landowners—including the county—must comply with the requirements. That mandate was stressed in a motion by Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich after the Department of Public Works issued rough, last-minute estimates indicating that the cost of replacing lights on the agency’s rural buildings would be so high that would be so high that they would have to dip into funds otherwise reserved for road projects.

“The Department of Public Works should find cost effective ways to comply with the ordinance like every other stakeholder, and they should do so out of their existing . . . budget,” Yaroslavsky and Antonovich said in their motion, calling the estimates “not credible.”

The new rules give county departments six months to report back on how they’ll comply. Homeowners will also get an initial grace period, after which enforcement will be based on complaints. For commercial and recreational facilities, such as ball fields and businesses, lights must be turned off either an hour after a game’s end, at the close of business or at 10 p.m., whichever is the latest.

Rural homeowners applauded the ordinance, championed by Antonovich and Yaroslavsky.

“Out here in the country, most people want to see the stars. And if your neighbor’s got tons of lights, and they don’t shut them off, it really does cause a problem,” said Wayne Argo, who lives in the Antelope Valley on three acres near the Angeles National Forestand who is director of the Association of Rural Town Councils.

“A couple of years ago, we had problems in Leona Valley with people using arena lights on their horse property and not turning them off at a reasonable time,” he said. “For the people in the area, it was like having a baseball field or a football field next door.”

As civilization has encroached on once-unspoiled horizons, city lights have eclipsed more and more of the night sky. Already, astronomers say, the Milky Way has become invisible in two-thirds of the country; after the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the Griffith Park Observatory reports, frightened Angelenos called when the power went out, wondering what the weird, silvery shimmer was in the night sky.

“Some thought it was the end of the world,” according to the observatory’s website. “It was, in fact, the stars.”

Some of the first calls for a curb on light pollution came from stargazers in Arizona. The city of Flagstaff passed one of the first anti-light pollution ordinances in 1958 to stop searchlights from impairing the work of astronomers at Lowell Observatory, where Pluto had been discovered. Then, in 1972, the city of Tucson began requiring city lights to be pointed downward to protect the Kitt Peak National Observatory.

By the mid-1980s, a state statute had been enacted in Arizona, and in 1988, astronomers in Tucsonfounded the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) to advocate on the issue. The IDA now has 58 chapters in 16 countries, helping draft model light pollution ordinances for communities.

In California, the city of San Joseswitched to low-pressure sodium lights in the 1980s to protect the nearby Lick Observatory; San Diego used regulations to dim the skies for the Palomar and Mount Laguna observatories as well.

In recent years, however, the dark skies movement has moved beyond astronomy to touch on environmental, health and lifestyle questions. The loss of darkness has, for example, also affected the feeding, mating and migration habits of wildlife from bats to sea turtles. Meanwhile, medical researchers have uncovered links between the incidence of breast and prostate cancer and exposure to artificial light at night.

In 2002, the city of Calabasas, which abuts the unincorporated Santa Monica Mountains, passed its own local light pollution ordinance, largely to preserve the rural character and local ecology of the community. According to a recent issue of the Las Virgenes Homeowner’s Association newsletter, in the last four years, the city has fielded only about nine complaints of light trespass, all involving commercial night lighting.

Both Lamorie and Argo hope further public education also will be a big part of the county’s light enforcement. And for those who are still not convinced of the new law’s value, Argo has a suggestion.

“You wait ‘til a half-hour or so after sunset, then sit down in a lawn chair, and lay your head back, and look straight up,” Argo said. “You can see satellites. You can see all the constellations. On a clear night, you can almost reach up and touch the Milky Way.”

Posted 1/24/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink