Seeing the forest and the trees

August 25, 2011

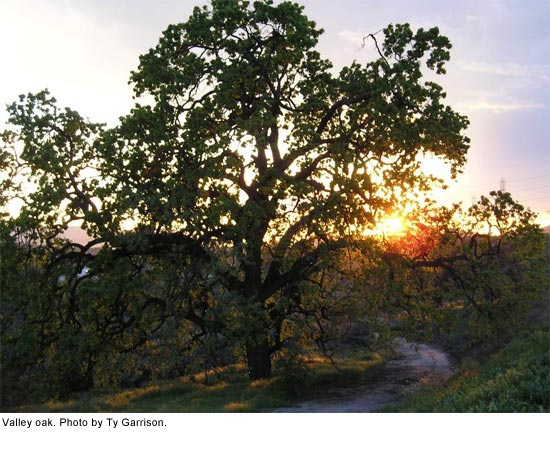

Few living things are as integral to Los Angeles as its mighty oak woodlands. They fed wooly mammoths and sheltered Native American tribes.

They’ve supported thousands of species of birds, mammals, reptiles and insects. They were remarked upon in the 1769 diaries of the awestruck Franciscan missionary, Father Juan Crespi. Even now, scattered though they may seem, they inspire reverence, rising from the chaparral like ghosts of another California. Unfortunately, as much as 80% of Los Angeles County’s original oak woodlands have been destroyed.

For the last several decades, environmentalists have waged an uphill battle to preserve the county’s 145,000 remaining acres of oak woodlands. Their successes have included a 1982 county ordinance that has made it difficult to cut down mature oak trees.

Still, the existing law is oriented toward regulating the removal of individual oak trees rather than preserving an entire ecosystem. As a result, while single trees enjoy some protection, the woodlands themselves—which filter pollution, absorb carbon dioxide, anchor stream banks and hillsides and slow floodwaters—remain vulnerable to everything from development to falling water tables. So on Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors took a step toward not only conserving L.A.’s beloved native species, but also toward making it easier for individual property owners to voluntarily do the right thing.

“The purpose of this is partly to raise the profile of this important ecosystem,” says Rosi Dagit, a senior conservation biologist at the Santa Monica Mountains Resource Conservation District who for the past three years has coordinated a strategic alliance of environmentalists, foresters, arborists, building industry representatives, fire officials and other interested parties in developing an oak woodlands management plan.

The group’s report offers two sets of recommendations. The first set, adopted by the Board on Tuesday, includes maps and a conservation strategy that make the county eligible for state woodlands conservation money that, in turn, will help buy land for public trusts and conservation easements.

The report also suggests ways that private property owners—who still control a quarter of the county’s woodlands in large tracts such as Newhall Ranchand small communities such as Topanga Canyon and Monte Nido—can voluntarily help preserve them by, for instance, donating land and easements themselves, thus reaping income, property and estate tax breaks.

The second set of recommendations, which was sent to staff for a report in six months on its potential for implementation, includes ways to incorporate oak woodland conservation into the general plan and important guidelines for such things as assigning a dollar value to a tree’s importance in mitigating global warming or as a source of flood control. It also includes a number of revisions to the existing oak tree ordinance.

For instance, Dagit says, under existing rules, property owners dread oak trees almost as much as they love them because they are required to pay for a pricey permit to cut one down after it reaches more than 8 inches in diameter.

“It’s several hundred dollars just for the permit,” she says, “and then you have to pay an arborist to do an oak tree report, which is several hundred more, and then if it’s more than one tree, you have to pay for a hearing, which can cost thousands of dollars. So typically, if a little oak tree volunteers in their yard, a lot of people don’t want the hassle—before it can reach 8 inches, they take it out.”

This is problematic, she says, because oak trees bind Los Angeles in more ways than Angelenos realize, from securing the soil and creating drainage to mitigating the city’s carbon footprint. “Each mature oak tree takes out nine tons of carbon a year,” says Dagit, “so we want to plant them, even if they’re only going to be around for 10 or 15 years.”

Under the proposed recommendations, property owners who might love to have a stand of oak trees but fear the potential for bureaucratic problems can head off future costs by planting trees themselves and providing a map (even a hand-drawn one) to the county.

“Then, ten years later, if you wanted to take out one of those oaks to put in a tennis court or whatever, you could do what you needed to do without a penalty,” says Dagit. “And meanwhile, the public will have reaped the benefit.”

This, she says, would be especially helpful in places like landfills, where oaks would be the perfect ground cover were it not for the owners’ fear of future impediments should a need to, say, get to some piping, require them to tear out a tree.

Dagit stresses that the current report is intended to make conservation easier, not harder: “We want to provide incentives for people so oaks won’t be considered a liability.”

But, she says, the woodlands continue to dwindle, and so far, not one section of oak woodland has been fully restored or recovered. “Trees are the background assumption of our life,” she says.

“People look out the window and think that the trees will always be there. But will they be?”

Posted 8/25/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink