The L.A. River’s stormy past

June 5, 2014

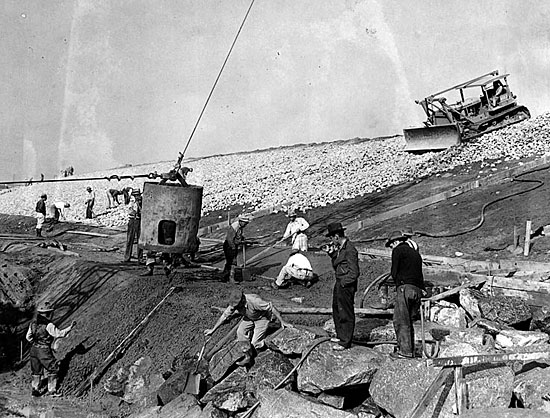

After pounding storms in 1938 brought death and destruction, the river would be tamed with concrete.

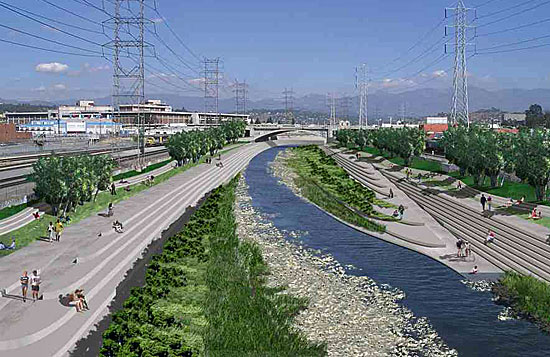

For decades, the Los Angeles River has been ridiculed across the country as being as fake as a Botox brow, maligned in its own backyard as nothing more than a 51-mile concrete eyesore. But the river’s image is about to undergo a game-changing makeover, thanks to the Army Corps of Engineers’ recent endorsement of a $1 billion revitalization plan, which more than doubled an earlier recommendation.

The plan to transform an 11-mile stretch of the river from Griffith Park to downtown L.A. is intended to give people of all ages a healthy urban getaway, where they can relax and play. But back in the days when the river was first encased in concrete in one of the nation’s largest Depression-era public works projects, the federal government’s investment was about much more than improving lives. It was about saving them.

The unpredictable waterway had killed hundreds of people during a series of storms that had repeatedly devastated the region over the previous half-century. Two particularly vicious wallops in the 1930s forced local officials to seek federal help. The first, in 1934, killed dozens of people in a watery siege witnessed by folk songwriter and poet Woody Guthrie, who memorialized it in The Los Angeles New Year’s Flood:

Whilst we all celebrated

That happy New Year’s Eve,

We knew not in the morning

This whole wide world would grieve;

The waters filled our canyons

And down our mountains rolled;

That sad news rocked our nation

As of this flood it told.

No, you could not see it coming

Till through our town it rolled;

One hundred souls were taken

In that fatal New Year’s flood.

But it was the urgency generated by a second deadly storm, this one in 1938, which brought the biggest infusion of federal dollars through the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration to protect the safety of one of America’s fastest growing regions. Between February 27 and March 3 of that year, Los Angeles, Orange and Riverside counties were drenched by more than 10 inches of rain. The river jumped its banks and flooded a third of the city, killing 115 people, while destroying or damaging more than 6,000 homes. Total property damage was about $1.44 billion in today’s dollars. (See video footage of the flood here.)

The Los Angeles County Flood Control District, overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers, put 17,000 people to work on the job at the height of the Great Depression. Almost all of the work was done by hand. They moved 20 million cubic yards of earth, poured 2 million cubic yards of concrete, laid 150 million pounds of steel and set 460,000 tons of stone. The entire length of the L.A. River was channelized, along with 147 miles of tributary channeling. Also built were 5 flood control basins and 316 bridges.

The transformation of the river took 20 years to complete.

By the time it was finished, the L.A. River was unrecognizable from its natural state. About 90% of it had been lined with concrete along its sides and bottom. A natural riverbed was kept for the remaining 10%. Formerly a home for frogs, fish and birds, the river became a graffiti-scarred channel for urban runoff and garbage, sending pollutants of various sorts speeding towards the sea. It was immortalized in movies like Grease and mocked by comedian Conan O’Brien.

It was, in short, a river in name only—a reputation that restoration leaders are now determined to change, while maintaining the river’s ability to control flood waters.

In addition to the billion-dollar revitalization project, there are ongoing efforts to build a continuous 50-mile bike path and greenway along the river. Last summer, a pilot kayaking program was launched in the Elysian Park neighborhood. Based on its success, the L.A. City Council voted in February to make the program permanent, while expanding it to another section of the river, the Sepulveda Basin.

So for now, although the history of the L.A. River is still being written, a new chapter has opened.

Posted 6/5/14

When the waters of the deadly '34 storm receded, this is what Montrose in the Crescenta Valley looked like.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink