Fixes on TAP at Metro

January 30, 2013

You griped, they listened.

As Metro prepares to finally latch its subway gates this summer, the agency’s transition from paper tickets to the mandatory plastic TAP cards needed to make the new system work has been rocky at times.

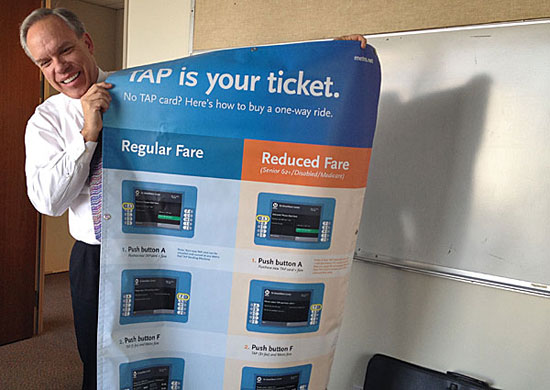

New or occasional users complained that they couldn’t decipher the jargon and complicated instructions displayed on vending machine screens. Senior citizens said it was impossible to figure out how to buy a reduced-fare ride. And transferring passengers protested inconvenient detours that, in some cases, force them to go long distances to tap their cards before returning to the train platform and continuing their trip.

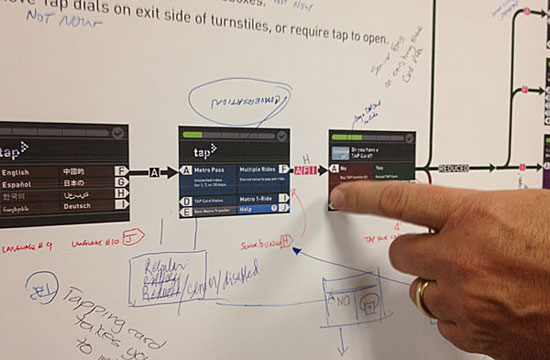

But help is on the way. Metro is overhauling the signage around its vending machines in an effort to make the process clearer and also has tweaked the on-screen instructions for people trying to buy a ticket. Behind the scenes, a broader do-over of the computer screens is underway, with a series of focus groups offering input on how to create a truly user-friendly process.

In addition, the agency is relocating “stand-alone validators”—which customers must touch with their TAP cards to legally board the train—at 24 stations. Those include the Wilshire/Vermont station, where passengers transferring between the Red and Purple lines must hop on an escalator or hike up and down 200-plus steps if they want to play by the rules and tap their cards before boarding.

“That was ridiculous. That was just not acceptable,” said David Sutton, Metro’s director of TAP operations. He said the sheriff’s department isn’t citing people in problematic areas—places where a customer has to “leave a rail platform, go upstairs, tap, come back down” in order to fulfill the law.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department is issuing plenty of other citations, though—69,839 of them between February, 2012 and the end of December, 94% of them for fare-evasion.

The transition toward locked turnstiles marks a major turning point for Metro riders in Los Angeles, who, unlike passengers in cities like New York or San Francisco, have until now traveled effectively on the honor system.

There is some debate over how much additional revenue locked gates will generate. (In 2008, when the agency’s board approved installation of a $46 million barrier gate system, it was estimated that fare-beaters cost the system $5.5 million a year, and that the system would eventually pay for itself.)

But there’s no question that the march to locked turnstiles has been challenging and complex. In addition to issues with confusing vending machines and poorly located validators, the agency also has had to grapple with how to make Metro’s new system work for thousands of regional commuters on Metrolink, which uses paper tickets.

A paper ticket with an embedded smart chip has been developed for Metrolink passengers, and on the fourth floor of Metro’s Gateway Headquarters this week, employees in the agency’s ticketing lab were busily testing prototype tickets to make sure they worked like a TAP card to open the gates. Broader field testing is planned in the weeks ahead.

The rush of activity is intended to meet a June deadline for beginning to lock the gates on the Red and Purple lines. (That work is expected to wrap up by the end of August. After that, latched turnstiles will be coming to the Green Line and portions of the Blue and Gold lines.)

With that in mind, Sutton and his staff also are scrambling to complete work on the revamped computer screen design by June. Up to $250,000 has been allotted for the project, which includes six to eight focus groups and a series of community meetings.

“We want to ask people who’ve never used our equipment: ‘Can you make a purchase? Try it.’ And if they can, it’s thumbs up. If they can’t, then we need to find out where the problem happened,” Sutton said. “We want them to just go up to the machine and do it.”

Two focus groups held so far—one in English, one in Spanish—“gave us a lot of good input about what they wanted,” Sutton said. “They wanted this A-B thing: ‘If I have a TAP card, I want a shortcut. If I don’t have a TAP card, I want you to tell me that I need a TAP card and why.’ ”

Sutton said that focus groups weren’t consulted originally as the agency hastened to accomplish the transition from paper to plastic.

Getting a second chance to hear from the public now is invaluable.

“We have this golden moment that we can actually step in and right any wrongs and make it a better system. Not many government agencies really have this opportunity to get things straightened out,” Sutton said. “Did it work before? Absolutely. We’ve got 20 million taps a month. So you know something’s going right…But we have a great opportunity at this point to look at it differently, to step out and reconsider, and I think that’s what we’re doing right now.”

Beyond the multifaceted efforts to revamp and improve, with more than 2 million TAP cards now in circulation and all of the region’s municipal bus operators now onboard, there’s evidence that the public is getting more comfortable with the system.

“We don’t get as many complaints anymore,” Sutton said. “I’m not getting any love letters, but we’re doing all right.”

Sutton and his team are going back to the drawing board to create more intuitive vending machine screens.

Posted 1/30/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink