County crackdown on numbers racket

September 2, 2010

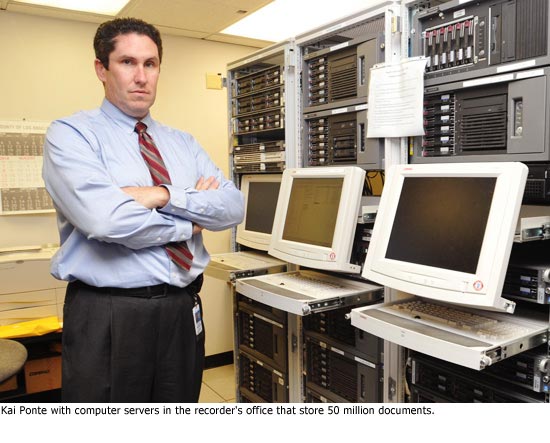

Identity thieves, meet Kai Ponte.

Ponte is overseeing an unprecedented technological effort by Los Angeles County to conceal Social Security numbers on millions of documents filed with the Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk during the past 30 years.

The project, mandated by California law, is aimed at protecting consumers by depriving crooks of information they can use to steal identities and inflict havoc on the lives of their victims. Social Security numbers—once routinely included on many kinds of official documents—are highly prized in this world of high-tech theft.

Ponte, who supervises the management systems team in the recorder’s office, understands the stakes and offers this warning to the growing legions of rip-off artists: “Go look somewhere else because you’re not going to find anything here.”

The state law, which went into effect last year, was authored by Assemblyman Dave Jones of Sacramento, a longtime advocate of consumer privacy legislation. To make his point on the need for this one, he initiated a public records search of some of the elite of Sacramento’s business community.

“We pulled up a wealth of information, including their Social Security numbers, which experts repeatedly told us was the most important piece of information to have if you wanted to steal someone’s identity,” Jones says. “We didn’t name names because we didn’t want to have a race to the recorder’s office by identity thieves, but we did mention the people by category—a CEO, a prominent developer, a banker.”

No one, of course, could have predicted decades ago, long before the Web revolution, that the millions of documents being filed with counties could some day become gold-plated invitations for criminality. Dean Logan, Los Angeles County’s Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk, says the redaction project was crucial in making records of the past safe for an age in which so much personal information is accessible through online databases. Although the law covers documents dating back to 1980, Los Angeles County is beginning with 1977.

“What we’re doing is balancing the purpose of maintaining a public record while eliminating the risk that it can be used to steal somebody’s identity,” Logan says, adding that, for the most part, complete Social Security numbers no longer appear on documents filed with the recorder’s office.

Under the new law, every county recorder is required to keep an unaltered “official record” and a “public record” that masks the first five digits of a person’s Social Security number.

“Most counties thought, ‘We’ll just make two copies,’ ” Ponte says. That’s an easy fix for a county like Modoc, which handled only 3,286 documents last year, Ponte says. “But in L.A. County we do between 2 million to 3 million annually, so we certainly didn’t want to create two copies.”

To that end, Los Angeles County launched the most technologically sophisticated strategy in the state to conceal Social Security numbers—a strategy that got a boost this week when the Board of Supervisors approved a key contract worth potentially as much as $821,370. Under that contract, Neubus Inc. will make digital copies of 20 million pre-1992 documents that now exist only on microfilm.

This digital conversion is essential to L.A. County’s unique approach. Instead of making a duplicate set of records like other counties, officials here will use software that searches documents for Social Security numbers and then automatically masks them before the record is viewed by the public. The old microfilmed documents can’t be altered unless they’re converted into digital files. The 50 million documents filed since 1992 already are digitized.

In all, Ponte estimates that of the tens of millions of documents that will be scanned, about 10 percent of them will have Social Security numbers that need to be masked. Virtually all these documents are related to property transactions of various sorts. Registrar-Recorder officials estimate that the project could take up to five years to complete.

As for the program’s cost, it’s being covered by a fund created through the state law and fed by a $1.00 fee the county collects on each recorded real property document. In other words, says registrar-recorder Logan, “we’re not taking something away from the general fund at a time of fiscal crisis.”

Logan also noted that, given the bad rap that public officials sometimes deservedly earn, projects like this one—designed entirely with the public’s protection in mind—“should make people feel good about their government.”

Posted 9/2/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink