Gunmen confront “lucky” health workers

May 26, 2010

The two L.A. County mental health workers felt confident there was little potential for violence lurking inside the Gardena apartment where they’d been dispatched to evaluate a man who, according to his mother, was “acting bizarre.”

As always, before even arriving, they’d assessed the risks.

“Does the patient know we’re coming?” they asked the mom, who had called the Department of Mental Health’s crisis line. “Has he been hospitalized before? Does he get violent? Has he hurt anyone today? Is he suicidal? Homicidal?”

The answers to these questions and others convinced them that, while the man was manic and “hyper religious,” he probably was not dangerous.

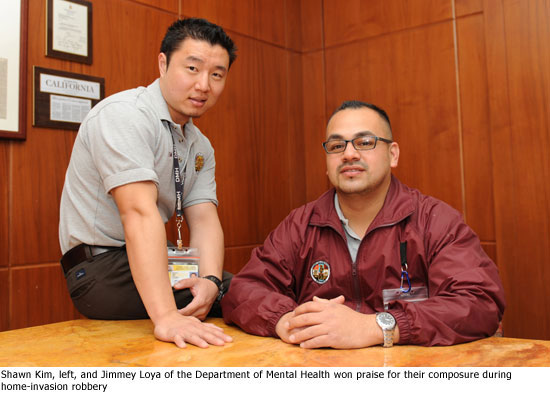

What Jimmey Loya and Shawn Kim could not have foreseen at that moment was that the real danger was bearing down on them from the outside and that their bipolar patient would, strangely enough, be the one to save the day.

On Tuesday, Loya and Kim, who are members of one of the county’s Psychiatric Mobile Response Teams, were praised by the Board of Supervisors for their professionalism and cool headedness during a harrowing, March 29 home-invasion robbery by three gunmen. Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, in whose district the events occurred, called the mental health workers heroic.

Both men, who’ve been employed by the county for less than a year, say the incident illustrates the unpredictable and largely invisible nature of their work. Not a day goes by, they say, that they don’t feel lucky to be alive.

Loya and Kim say they arrived in Gardena at about 6 p.m. Loya, 34, is a registered nurse. Kim, 29, is a psychiatric social worker. As part of a multi-disciplinary team, it’s their job to determine whether patients require immediate hospitalization or should be referred to outpatient services. With each call, the teams enter a universe of uncertainties.

In this case, the pair had been dispatched to a second-floor apartment in an industrial area of Gardena with a reputation for gang activity. When the door opened, the patient said simply: “Come on in. Let’s get this over with.” Arrayed behind him was his support system—his mom, dad, uncle and aunt.

Loya and Kim quickly sized-up the place, looking again for dangers and ways to make their visit safer. They made sure, for example, that all the lights were on. They looked for weapons and kept the front door wide open so that they’d have a fast escape should something go wrong. They then all took a seat around a dining room table, except for the aunt, who stood behind her nephew.

Loya and Kim soon concluded that the patient did not meet the criteria for involuntary hospitalization. He was denying any homicidal or suicidal thoughts. He was not hallucinating. He was loud but not hostile. He was polite and approachable—although that behavior was about to dramatically change.

As the mental health workers were providing the patient with a referral to Harbor/UCLA medical center, three men brandishing handguns burst into the apartment through the open front door.

“Nobody move!” they shouted. “Take everything out of your pockets and place it on the table!”

“I can’t believe this is happening,” the aunt exclaimed. “Is this for real?”

Kim, for his part, was praying that their patient would remain calm and not escalate the situation. “Of course, that didn’t end up happening,” he says.

Instead, the patient suddenly shouted: “How dare you come in here with two officers in my house!” Kim and Loya say their hearts sank. They now feared that the gunmen might kill them in a mistaken belief they were cops. “We’re definitely dead,” Kim thought to himself. “No way we’re going to get out of this anymore.”

The gunmen moved more menacingly toward the mental health workers. “I could feel the gun on the back of my head,” Loya says. “I could feel the barrel. I knew I was going to die.” Loya says he thought about his four young children, the oldest of them 9. But he says he knew that, with a mom who’s a nurse practioner and a sizable life insurance policy to collect, “they were going to be OK. I accepted death.”

The patient was in a different state of mind. He jumped up out of his chair, ripped off his shirt and ran straight toward the armed invaders, screaming, “Kill me! Kill me! Kill me!” The gunmen, startled, headed for the door and then down the stairs, chased by the muscular patient.

“When our client got up, I thought we were doomed. But it caught them by surprise,” Kim says of the robbers. “They didn’t expect anything like that. It didn’t seem they were ready to kill anybody. We were very fortunate.”

When the patient strode back into the apartment, he shouted: “That’s the power of God! If I would have died today, I would have gone to heaven.” He then looked at the county workers and said, “Do you think I have a problem now with my anger?”

“On the contrary,” Loya says he responded. “you’re my hero.”

Loya and Kim say that, as you might expect, their bosses in the Department of Mental Health have been especially attuned to potential psychological trauma they may have suffered from the incident, in which no arrests have been made. Both say they returned to work quickly and are doing well.

Loya says that one thing he does differently these days when entering an unfamiliar home is to keep his hand on his BlackBerry with 911 already punched in and ready to send. He says he also has a new response when people ask how he’s doing: “I feel good. And I’m alive.”

Posted 5/26/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink