Metro’s lost world

July 27, 2011

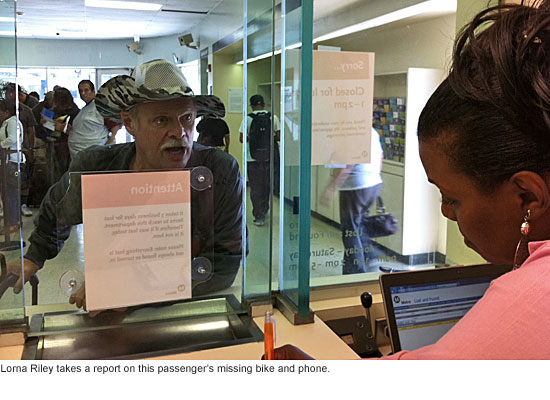

Forgetful transit riders, Lorna Riley has your back—and your backpack.

Forgetful transit riders, Lorna Riley has your back—and your backpack.

Also your keys, mobile phone, mountain bike, prescription medication, “Lilo and Stitch 2” DVD and quite possibly your dry cleaning.

Riley, the doyenne of Metro’s Lost and Found, has seen just about everything in her 13 years with the agency—including a human jawbone (part of a college science experiment), a district attorney’s gang file (quickly returned to its official owner) and a memory stick full of JPL data (ditto.)

“We get it all,” she says.

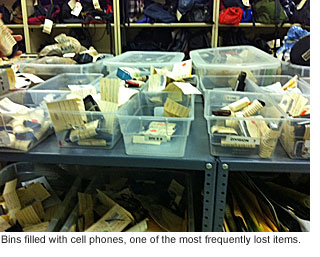

But this week, Riley’s encountering something that even she’s never seen before: a new computerized system in which a barcode is assigned to each of the thousands of items left aboard Metro trains and buses each year. The items are logged in a computer database, making quick scans for likely matches possible. And the traveling public can now submit online claim forms for missing items. A personal visit to the Lost and Found, located in Metro’s Wilshire/LaBrea Customer Center, is still required to pick up missing things, although Riley will mail items to out-of-towners.

“We’ve shipped stuff back to Australia,” she says. “Being L.A., we get a lot of tourists. France, China, Belize.” Not too long ago, a teenager from Georgia, in town for a Boy Scouts gathering, left his backpack on the bus—fully loaded with all his electronic devices. While he won’t be winning any merit badges for keeping track of his stuff in transit, he did remember to place a luggage tag on the pack, enabling Riley to track down his mom and reunite the scout with his wayward backpack.

Alan Gee, Metro’s manager of Customer Programs & Services, says he hopes the new system will make that kind of happy outcome more common. As it is, he estimates that up to 50% of bicycles and up to 30% of other items end up being claimed by their owners; he’d like to see that increase to 75% for bikes and 50% for other things. “We don’t want this stuff,” he says. “Come and get it, please!”

Alan Gee, Metro’s manager of Customer Programs & Services, says he hopes the new system will make that kind of happy outcome more common. As it is, he estimates that up to 50% of bicycles and up to 30% of other items end up being claimed by their owners; he’d like to see that increase to 75% for bikes and 50% for other things. “We don’t want this stuff,” he says. “Come and get it, please!”

Tucked away behind the scenes at the bustling Customer Service center, the Lost and Found is a crowded jumble of artifacts abandoned by a metropolis in motion.

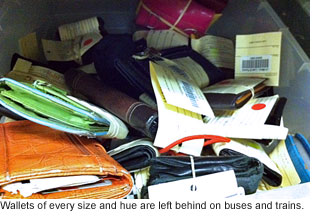

Wallets of every color and size are bundled together in a bin. Abandoned shopping bags are grouped according to where they were found. Guitars share shelf space with a forlorn carpet cleaner. An entire room is dedicated to bikes. Forgotten dry cleaning hangs on a garment rack in a hallway.

There are rolls of toilet paper, rolls of blueprints, a tube of toothpaste, a surprising number of crutches and seemingly enough backpacks and suitcases to rival baggage claim at LAX, or at least Burbank.

“Every time I come here, I’m just baffled,” Gee says. “I mean, really?”

The new database doesn’t have the same atmosphere as the Lost and Found itself—in a renovated Miracle Mile building that was once the setting for Tilfords Restaurant and Coffee Shop—but still manages to convey a sense of the varied lives passing through the transit system. Some recent entries: “alcoholics anonymous book and pen,” “1 black wallet with $3.00,” “red framed glasses.”

“We see the full spectrum,” says Riley, 54. “Due to the economy, I think more people are riding public transportation. We get a lot of people, from the homeless to the mayor’s office.”

While the new automated system is expected to make it easier to match up missing items with their owners, the human touch is still essential.

While the new automated system is expected to make it easier to match up missing items with their owners, the human touch is still essential.

Earlier this week, Riley, who previously worked in retail and ran her own party events/corporate gift business, patiently met with a steady parade of passengers who’d left something behind on the bus or train.

“We’ll keep a lookout for it,” she told one woman, who was seeking a red Ed Hardy hoodie she’d left on the bus from downtown to the beach. “Give it a couple more days, OK?”

The passenger had lost the pullover a few days ago, and held out scant hope of seeing it again. “I doubt it, but it’s worth a try,” she shrugged before leaving the window.

Sometimes the customers are more frustrated than resigned.

“They’re angry with themselves because they lost it,” Riley says. “Sometimes they’re so upset that it’s hard to tell what they’re looking for. I’m pretty good at calming people down.”

Riley prides herself on being able to find her way to the items she’s logged in using a color-coded system that she developed.

And she knows her repeat customers.

“I have one regular who loses his bike. He lost it three times in one month. He almost uses Metro as public storage.”

She’s even had father-daughter and father-son teams—in which both got off the bus and left their bikes behind.

Items not claimed after 90 days are auctioned off or donated to charity. Still, some things linger longer, like a Barbie tricycle, still in its bright pink box, that was left on a Blue Line train last December and is still waiting for someone (Santa Claus?) to pick it up and deliver to its rightful owner.

When she can, Riley plays gumshoe. “I have a little file that I call research,” she says. By tracking down leads and calling around, she’s been able to locate and return important documents, such as death certificates and burial permits, as well as objects of sentimental value, like wedding photos.

“Usually,” she says, “I go home with a good feeling because I’m helping people get their things back.”

Posted 7/27/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink