Sheriff hits milestone on rape kit tests

October 14, 2010

There was a time, not so long ago, when the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department seemed committed to resisting the inevitable, rebuffing advocates who wanted to know whether the agency was sitting on a backlog of untested rape kits.

It was mid-2008, after the Los Angeles Police Department disclosed it had more than 7,000 untested kits in storage behind Parker Center. The issue had entered the universe of politics, becoming a test of sorts of police responsiveness to the concerns of women.

But the Sheriff’s Department wouldn’t budge when a researcher for the group Human Rights Watch filed a series of Public Records Act requests for the information. The department stated that it would be “prohibitively time consuming” to count the kits—a response that Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky found unacceptable. At his urging, the five-member board directed the Sheriff’s Department to begin counting.

That was two years ago this month, a milestone that has now led to another. Not only have the kits been counted, all 4,763 of them have been outsourced for testing. Although they’re far from being fully processed—only about half so far have been found to contain usable DNA—sheriff’s officials and women’s advocates surprisingly are in agreement on this much: the process is going better than expected.

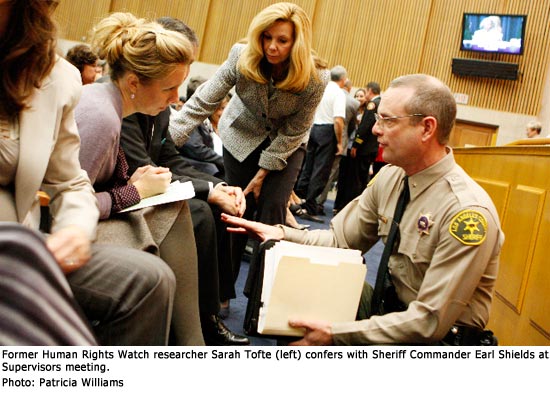

“I can remember a time when we couldn’t even get them to acknowledge there was a backlog,” said Sarah Tofte, the Human Rights Watch researcher whose records requests were rejected. “To be at a point now where they’ve sent out every kit, my gosh, that’s a big deal. I think it’s very definitely something to be celebrated, even if it’s not the end of the road.”

Tofte, who now works for actress Mariska Hargitay’s Joyful Heart Foundation, was the driving force behind Human Rights Watch’s 2009 report on untested rape kits in the Sheriff’s Department and LAPD, which also has now outsourced virtually its entire backlog.

There are many in law enforcement who privately argue that it’s unnecessary and wasteful to test every kit for DNA evidence, especially when the suspect’s identity is known or he’s been arrested. Under California law, a DNA sample is taken from all felony arrestees and entered into a database. Critics say that in these cases, there’s no need to test the kit because the suspect’s DNA already is in hand.

But advocates and others in the criminal justice system contend that there’s too much room for error in exempting certain types of kits, for which victims undergo a meticulous forensic examination. They say the broad discretion historically given detectives to determine whether kits are tested has resulted in botched opportunities, potentially leaving rapists on the loose.

Advocates note, for example, that the vast majority of rapes are perpetrated by acquaintances with a pattern of such behavior with other women. Although the suspect’s name may be known to police, if he’s not arrested, he won’t be swabbed under the California law. But the forensic evidence could connect him to other sexual assaults in which kits have been tested and uploaded into the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, database. This is what New York authorities found in processing its 15,000 warehoused kits.

In Los Angeles, however, the debate is now moot because Sheriff Lee Baca and LAPD Chief Charlie Beck both have directed that all rape kits—past and future—be tested.

The man responsible for executing Baca’s directive is Commander Earl Shields, who oversees the department’s crime lab operations. He says the huge mobilization has provided unexpected benefits to the department, beyond confronting the mass of untested sexual assault kits, as they’re called in law enforcement circles.

With new hires and equipment, Shields said, “we’ve built up a tremendous capacity in the lab. What that positions us to do in the future is to look at other investigative uses of DNA.”

Through an agreement between the Sheriff’s Department and the county’s Chief Executive Office, the lab has added six criminalists, with two more on the way thanks to a $1 million federal “Rape Kit Reduction Program” grant.

So far, the testing itself has cost $3.1 million—far less than the department initially predicted—according to the sheriff’s most recent monthly status report on the effort. Most of that money has come from a more concerted use of federal DNA grants. Only a fraction of the $2.3 million the department allocated from its budget has been tapped.

Shields said the sheriff achieved substantial savings by playing the private labs against each other. “We told them, ‘We have a whole lot of cases. The better the price, the more we’ll send. ’ ”

But there’s also been a downside. The crush of kits moving through the system has created a new backlog of nearly 1,000 kits awaiting “technical review” of the work done by the private labs, which are not allowed to upload the results into the DNA database. According to Shields, this verification process can vary greatly in complexity, possibly requiring even more investigative work by detectives.

Shields said he expects these cases to be reduced more quickly in the weeks ahead as the lab’s newly hired criminalists are trained. “Our ability to do technical reviews is increasing all the time,” he said.

As of October 1, according to the department’s status report, DNA from only 673 kits has been uploaded into the CODIS database. Of those, there have been 305 matches involving department cases, 227 of which are currently under investigation. Seventy-eight cases are closed, 17 of them resulting in criminal charges prior to the testing. So far, the department said two criminal filings are directly related to the testing. The District Attorney’s Office has rejected 38.

No one knows more about the importance of rape kits—or speaks more forcefully on the topic—than Gail Abarbanel, who 36 years ago founded the pioneering Rape Treatment Center at Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center. There, she has created a safe environment for women traumatized by sexual assaults to receive, among other things, emergency medical care, forensic services and counseling.

“When it was discovered that thousands of kits were sitting in storage facilities and never opened or processed,” Abarbanel said, “it was really a metaphor for how rape victims are discounted in the criminal justice system.”

Abarbanel said she, too, is encouraged by the Sheriff’s Department’s progress.

“I commend them for sending kits to be tested, but none of these cases are completed until the results are in the hands of the detectives investigating the cases and the offenders who’ve been identified are arrested and off our streets,” Abarbanel said. “There’s still thousands of rape kits across the country that have not been processed. But what’s different in Los Angeles today is that we have an absolute commitment from the sheriff that every kit will be tested. I feel confident he’ll do the right thing.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink