An heiress with heart

April 7, 2011

There’s not a whiff of wealth around Aileen Getty. Her fingers are circled not with diamonds but with intricate tattoos. She wears bright yellow sneakers and sanely-priced jeans. Her face is free of makeup, warm and welcoming.

Aileen Getty’s grandfather was the billionaire oil baron J. Paul Getty. But these days she has found richness in her life on the far margins of society. A former heroin and cocaine addict who has been living with AIDS for more than two decades, she has emerged as arguably the most influential friend and benefactor of the homeless of Hollywood.

“I’ve been able to grow alongside them,” she says, “while they grow alongside me.”

During the past five years, Getty, 51, has quietly contributed millions of dollars to provide housing and food for Hollywood’s entrenched homeless population through her Gettlove organization and through gifts and loans to several other advocacy groups. By all accounts, she’s changed the landscape.

Getty says her own “inability to get well” has created in her a natural affinity with those struggling on the streets, most of whom are plagued by mental health and substance abuse problems.

“I’ve been an addict most of my life,” says Getty, who celebrated five years of sobriety on Valentine’s Day last month. “In my own journey, I really felt like I could either die or say, ‘Thank you and I’m sorry.’ I felt I had taken far more than I’d ever given. I didn’t want to go out that way…I rewrote my interior geography. That geography is now about others. ”

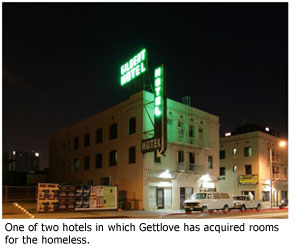

Gettlove, founded in 2005, has provided a variety of housing alternatives, depending on the needs of its clients. That includes refurbishing 30 rooms at two 1920s-era Hollywood hotels and lining up apartments for nearly two dozen homeless people in an aging Santa Monica Boulevard building. There, Gettlove staffers help tenants manage their finances and adjust to life with a roof.

At the same time, Getty individually has funded other organizations—Step Up On Second, PATH and Housing Works—to help them develop permanent housing for residents who simultaneously receive such services as health and mental health care. This month, Getty’s efforts led to her being honored as “woman of the year” for Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s Third District.

At the same time, Getty individually has funded other organizations—Step Up On Second, PATH and Housing Works—to help them develop permanent housing for residents who simultaneously receive such services as health and mental health care. This month, Getty’s efforts led to her being honored as “woman of the year” for Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s Third District.

Underlying all of Getty’s financial and logistical contributions is her core belief in the power of one-on-one relationships to, in her words, “rekindle the part of a human being that wants to find its best self.”

“Just because we’re housed doesn’t mean our spirit is comfortable,” says Getty, whose organization has taken clients on outings to, among other places, the L.A. County fair and the horse track.

Beyond housing, Gettlove serves hundreds of breakfasts and lunches each week at a social services agency founded by Blessed Sacrament Church in Hollywood. Gettlove shares the Selma Avenue building with several other homeless advocacy organizations, a reflection of the growing coordination among non-profits, business owners and government agencies to reduce homelessness in Los Angeles’ most famous neighborhood. A 2009 count by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority found more than 1,000 individuals living on the streets of greater Hollywood, half of them young people.

Getty can often be found at Blessed Sacrament’s social services facility spooning out food in the industrial-sized kitchen or mingling with clients in the dusty courtyard. Most have no clue about the family ties of the soft-spoken woman, who treats them as though they were her only family. But some have heard the buzz.

Getty can often be found at Blessed Sacrament’s social services facility spooning out food in the industrial-sized kitchen or mingling with clients in the dusty courtyard. Most have no clue about the family ties of the soft-spoken woman, who treats them as though they were her only family. But some have heard the buzz.

“I hear you’re one of the Gettys. Is that true?” they’ll ask. When Getty says yes, the matter quickly passes because her commitment to them has already become the defining characteristic of their relationship.

“The clients know me for what I do with them each day,” Getty says, “not what I give to them each day.”

That said, Getty also knows her wealth is central to Gettlove’s effectiveness, giving her an edge over traditional service groups that must be accountable to the agencies that fund them. “I’m not dependent on anyone else’s expectations,” she says.

This extraordinary financial freedom allows Gettlove to experiment, to learn what works and then collaborate with government agencies to bring to life these “best practices” models.

Says Getty’s longtime friend and fellow Gettlove board member, John Ladner: “We’re taking advantage of our inexperience. We have the advantage of not too many set-in-stone obstacles.”

Looking ahead, Getty believes that providing homes to the homeless should not be embraced as an end in itself. “Nothing is solved,” she says, “unless we nurture a sense of community.” To that end, she envisions the development of community centers, where the homeless and the newly housed can gather during the day and enjoy the restorative powers that come with companionship and “a true sense of belonging.”

Among other things, she says these centers would offer everything from movies to gardening. “Someplace where people get to laugh,” Getty says—something that, these days, comes much easier in her own life. Says Getty: “I’ve become a more comfortable human being.”

Posted 3/24/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink