The new kids on campus

December 1, 2011

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Mauricio had been informed that he’d been picked to participate in an unprecedented summer experiment on the UCLA campus, one that aims to infuse ambition and confidence into a group of kids who rarely go to college mostly because there’s been no one to help them get there.

Mauricio says he packed his suitcase a full month before the start of the intensive, five-week program and arrived so early on the first day that the former sorority house where he and the others would be living was still empty. “I was just so proud,” he says.

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students.

On Friday, that pride was shared by plenty of others—but, most importantly, by the 24 inaugural graduates of the First Star UCLA Guardian Scholars Summer Academy, the first such academic program of its kind for foster kids and others under the jurisdiction of child welfare officials. The youngsters, all of whom will be entering 9th grade, were honored during a commencement ceremony highlighted by one girl’s rousing exclamation: “I’m a Bruin now!”

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students. (Click here for a video on the program produced by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.)

The program’s supporters say they’re determined to shatter the shameful statistics surrounding foster children, huge numbers of whom end up homeless and incarcerated in the years after their 18th birthdays, when they “age out” of the system. Only a fraction of them—an estimated two percent—continue their educations beyond high school.

“You can argue that college is their best possible ladder to leave behind a bad childhood and make it into a happy adulthood and a productive one that will not be a burden on the state, that will be something of high accomplishment,” says media executive Peter Samuelson, a driving force behind the program through his non-profit group First Star, which joined forces with UCLA and the County of Los Angeles.

“There’s nothing the matter with these children. Not one of them,” he says. “All of these kids can go to college. The issue is that nobody ever told them they could. How dumb is that? Who’s failing here, the kids or the grownups?”

The Summer Academy was designed to jump-start the participants’ collegiate careers and expose them to the rigors and culture of university life at a crucial juncture, just as they’re entering high school.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

And then there were the field trips to, among other places, Disneyland, Skid Row and celebrity Chef Mario Batali’s restaurant, Mozza, where one teenage girl sheepishly confessed to eating nine slices of the establishment’s famed pizza. (The Batali Foundation also contributed money to the Summer Academy, along with the Stuart Foundation, College Board, Sage Publications and Hasbro Children’s Foundation.)

“It scares you in the right way,” Tiffany, 14, says of the program’s morning-to-night regimen. “You know what you’re being pushed to do. A lot of people say, ‘Oh, I want to go to college.’ But until you actually see college kids and what they do and their level of intelligence, it’s hard to say yes.”

Initially, 30 students were selected for the program. But six boys were sent home in the second week for bad behavior, a wrenching decision for all involved. Still, academy officials had no intention of joining the long line of adults who’ve abandoned or given up on such boundary-pushing kids, a reflection of the program’s commitment to—and understanding of—its charges.

Program leaders have remained in contact with the remorseful teens and have held out the promise that they can participate in the group’s monthly UCLA gatherings and, if all goes well at home and in school, they’ll be able to join next summer’s class of young scholars.

“They’ve been told, ‘You are fine young men.’ They’ve all been given hope and a shining pathway of behavior to get themselves back in,” says Samuelson, who raised $305,000 for the summer academy. “When we get these six young men back into the academy, they will count amongst our greatest successes.”

Day to day, the program is run by a seemingly unflappable educator and former vice principal of an elementary school in a tough New Jersey neighborhood. “I fell in love working with students who felt that nobody else cared about them,” says academy director Wally Kappeler, 37, the father of an eight-week-old son.

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

Kappeler says another boy, shy and self conscious about his weight, would mostly keep to himself like “an outcast” until he was given a special daily job of locking a rear door at their three-story Hilgard Avenue house after deliveries by the caterer.

“He felt so proud that this was his responsibility that he volunteered for all kinds of jobs,” Kappeler says. “He volunteered to take the trash out to the dumpster and wipe the tables and make Kool-Aid for the entire group. And it became contagious…It’s amazing the inspiration that he’s been to us, coming out of his shell and taking a leadership role without saying much of anything at all.”

Because of such breakthroughs and the upbeat bonding between the youngsters, it’s easy to forget the circumstances that brought them to UCLA—the abuse and neglect, the revolving placements in new homes and schools, the philosophies of life that have evolved from the sadness of their situations.

Listen, for example, to Eddie, a soft-spoken 15-year-old, who confides: “Too much happiness could actually hurt you. You just need the right amount because I don’t want to get hurt anymore. Right now I’m not really in the mood for situations like love and happiness. I really want to succeed in my life.” Eddie says he’s determined to be the first in his family to attend college.

Or hear what Thalia, 14, has to say as she speaks for the many who’ve been betrayed by parents. “Even if they’ve done something bad to you, they’re still your blood and they’re part of you and you love them no matter what. And you will always forgive them, even though you’re mad at them at the moment. But they’re always going to be in your heart.”

Kappeler says his heart aches when he hears the kids talk like this. “The emotional baggage they’re holding onto is the stuff that most adults would use as an excuse to give up on life.” Instead, Kappeler says the academy is teaching students to harness the power of their narratives through writing, video and social media so they can become more effective advocates for themselves.

“I want them to feel like they can make a difference in this world just by being who they are and getting their story out,” he says, noting that each was given a laptop and video flip-cam to keep.

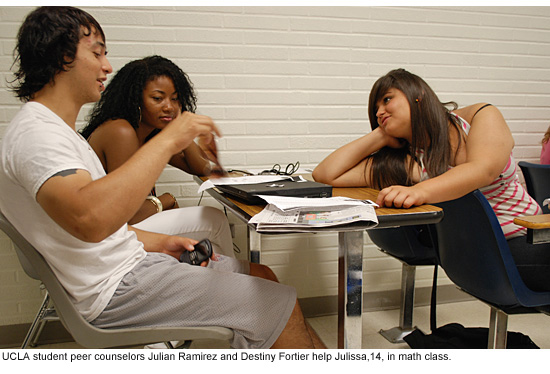

To guide and inspire the participants along the way, the program was staffed by peer counselors and resident assistants who are UCLA students and, for the most part, former foster youths themselves.

One of was senior Julian Ramirez, 21. As a youngster in San Jose, he endured a home fraught with addiction and violence. “One day my dad would say, ‘Let’s go fishing.’ The next, he’d be beating us with the fishing poles.” Under a mop of dark hair, Ramirez says he’s still got a scar from a concrete slab his father smashed against his head. Child welfare authorities, he says, repeatedly removed him and his siblings from his parents.

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

He says he hopes that his empathy and success—and that of the other student staffers—proved useful to the young teenagers in the summer program.

“I’ve been through a lot,” he says. “I know how it is to be 14, angry and not have anyone to talk to.”

In fact, the young participants told UCLA researchers late last week that the student mentors were “really impactful for them,” especially in the way “they talked about their journey through foster care,” says Associate Professor Todd Franke of the School of Public Affairs/Social Welfare, who’s conducting a longitudinal study of the students’ progress.

Franke says that, although it’s too soon to say much definitively about the program, there are some encouraging signs, based on a comparison of initial interviews with the teens and another series conducted on the eve of their commencement.

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

On Friday, commencement day, an assortment of foster parents, legal guardians and relatives gathered around dozens of tables inside UCLA’s Tom Bradley International Hall. There, they heard speeches about the heart and hope of the young Summer Academy participants. Among the officials who addressed the teens and their caregivers was Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, whose office helped facilitate the program through the Department of Children and Family Services.

He told the teenagers that, on some level, he could identify with their struggles. He said his mother died when he was 10 and that his father worked in the evenings, which meant there was no one to help him with homework or keep an eye on him at night.

“The thing that you have that most college students don’t have is that by the time you get ready to come into college, you probably will have gone through the toughest part of your life,” said the supervisor, a UCLA alumnus. “And while you may not appreciate that, you should embrace that experience, treasure that experience, because it’s going to toughen you up. It’s going to make you tough enough to confront whatever comes along your way, when you’re in college and after that.”

After the speeches were done and the two-dozen scholars received their graduation certificates—along with a standing ovation—it was time for them to leave this place of grownup aspirations and youthful good times. There were lots of hugs and tears, even though they’ll all be together again on campus in a month.

“I feel proud but at the same time I feel sad,” explained Mauricio. “I feel like this is my house.”

Video and photos by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.

Posted 8/7/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink