Former federal prosecutor Richard E. Drooyan is leading the investigation of deputy force in the county’s jails.

When it comes to police scandal and reform, attorney Richard E. Drooyan has found no shortage of opportunity in Los Angeles.

A former high-ranking member of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, he served on the Christopher Commission after the Rodney King beating and helped lead an independent inquiry into corruption by anti-gang officers in the LAPD’s Rampart Division.

Now, he’s back, this time as general counsel to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, a panel created in October by the Board of Supervisors to investigate alleged brutality and management failures in the county jail system. The commission is packed with marquee names in law enforcement and legal circles. But it’s the lesser-known Drooyan who’s largely orchestrating the historic effort—with the quiet help of some of Los Angeles’ most prestigious law firms.

Drooyan is drawing on a model that dates back to the Christopher Commission, one not widely known beyond Los Angeles’ legal community. Today, as in the past, he’s drafted an army of high-powered lawyers to conduct every facet of the investigation, assigning each with responsibility for a specific area of inquiry. Those attorneys, in turn, have dipped into the ranks of their own firms.

In all, some 50 lawyers, representing ten firms, have been pressed into action—without a single billable hour among them.

“Fortunately, there’s been a history of very talented lawyers in the town’s top firms who’ve been willing to devote pro bono hours to these kinds of investigations,” Drooyan said from his office at Munger, Tolles & Olson. “The reality is, you need experienced people who can devote a lot of time and energy but you don’t have the budget to pay them. If you were to add up the final billable hours for the jail commission, it would be north of seven figures.”

The payoff, so far, has been substantial. This unsung cadre of legal firepower has identified and interviewed scores of witnesses, reviewed hundreds of documents and, in a series of public hearings, elicited dramatic testimony suggesting that the department’s second-in-command contributed to a climate in which jail deputies used unnecessary force.

Commission Chair Lourdes Baird

The Commission’s chair, retired federal judge Lourdes Baird said the legal team has become “an integral part of our commission’s efforts” and “exemplifies the best of public service in our legal community.”

One of the recruited attorneys is Nancy Sher Cohen of Proskauer Rose, who calls herself a “worker bee for the commission.” Like Drooyan, Cohen also served on the Rampart panel. “Most of us tend to work on corporate litigation,” she explained. “Of course, you love your clients but this has a social justice piece that makes it very special.”

Bert Deixler, who served with Drooyan on the Christopher Commission and has been tapped for the jail study, says the unique investigative approach also provides newer attorneys with the experience of having societal impact while serving with seasoned law veterans across the city, a rare opportunity in a highly structured business.

“You take some young stars in your firm and say, ‘Here’s a chance to pay it forward.’ There’s a sense for all of us that this is part of what lawyers are supposed to do. It’s not just about collecting money,” says Deixler, a former member of the U.S. Attorney’s Office who’s now a partner with Kendall Brill & Klieger.

To get a feel for the job at hand, the recruited lawyers toured the troubled Men’s Central Jail on the edge of downtown, built mostly during the early 1960s. With more than 4,000 inmates packed into dark cells, it’s become the primary focus of the commission’s inquiry.

“For those who hadn’t seen it before, they came away from the experience feeling speechless,” said the commission’s executive director, Miriam Krinsky, who went on five of the trips. “It can’t help but hang with you.”

The attorneys assembled by Drooyan are a formidable group. Many are former federal prosecutors—skilled investigators with experience in analyzing data and coaxing reluctant witnesses to come forward. Already, their effectiveness has been on display during a series of headline-generating hearings during the past several months.

This was particularly true on May 14, when Drooyan presented as witnesses three retired jail supervisors. Their testimony went beyond the more familiar allegations of brutality and suggested that a series of moves by a top Sheriff’s Department manager undermined jail supervisors and led to higher levels of excessive force.

They described a culture in which longtime jail deputies—who, like some behind the bars, dub themselves OG’s, short for “Original Gangsters”—seemed to carry more clout than their bosses. Retired Sergeant Daniel Pollaro told of insubordinate deputies changing work assignments that their supervisors had created to break up “cliques” on floors throughout Men’s Central Jail. Retired Lt. Alfred Gonzales, meanwhile, recounted, among other things, the resistance he met while patrolling those floors in an effort to keep deputies in line and out of trouble, a practice not embraced by his predecessors.

But the testimony that raised the most eyebrows was Gonzales’ account of a meeting that then-Asst. Sheriff Paul Tanaka convened with jail supervisors in 2006, which followed an unusual closed-door session he’d held with complaining deputies.

“You guys are a bunch of dinosaurs,” Gonzales quoted Tanaka as saying. “Your supervisorial skills are antiquated.” According to Gonzales, Tanaka instructed the supervisors to “coddle” the deputies and to “stay off those floors and let those deputies do what they have to do.”

“The chain of command was totally broken,” Gonzales testified.

Tanaka, now the department’s undersheriff, is scheduled to appear before the commission in late July, along with Sheriff Leroy Baca. Neither has commented on last month’s testimony.

By all accounts, one of the biggest challenges for this commission—like others before it—is not only to identify witnesses but also to get them to testify publicly.

Drooyan said that Gonzales and Pollaro agreed to testify because after spending much of their working lives in the Sheriff’s Department, “they genuinely wanted to see issues addressed that were of deep concern to them.”

Sometimes, though, it can be tougher, especially in eliciting cooperation from current members of the department.

“They feel their careers are on the line,” said Fernando Aenlle-Rocha, a former federal prosecutor who’s now with the firm of White & Case. “We don’t have subpoena power and we can’t immunize people—the kind of tools that are given to prosecutors. You can just use your persuasive skills.”

So far, according to a recent commission status report, more than 150 potential witnesses have been identified between the five investigative teams created to examine the jail system’s management and oversight, use of force, culture, discipline and personnel. Each team will write a chapter for the commission’s final report, which is expected to be issued in early fall after more hearings. The full commission has met nine times to date. A committee held its first community forum on May 30.

Executive Director Krinsky stressed that the Sheriff’s Department and the commission have been extremely cooperative with each other. “It’s not a ‘gotcha,’ ” she said.

Drooyan agreed, adding that Baca himself has personally assisted in the commission’s requests for information.

“Everybody,” Drooyan said, “wants to improve the jail.”

Updated: At the Decemember, 4, 2012, meeting of the Board of Supervisors, Drooyan was appointed to oversee implementation of more than 60 reforms recommended by the jail commmision in its final report, which was released in September. Click here to read it.

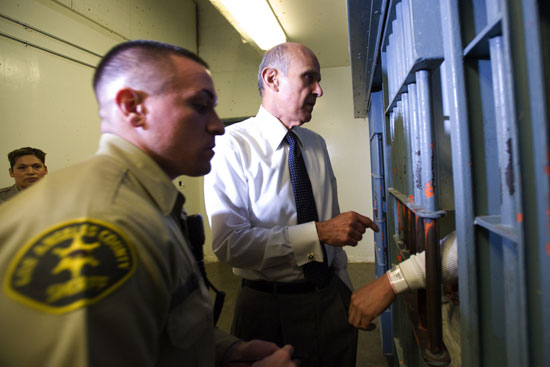

- Sheriff Leroy Baca, earlier this year, walking the floors of Men’s Central Jail in downtown L.A.

Posted 6/13/12