Our night on the streets

February 1, 2011

I’m often asked if there is a public will in Los Angeles to do anything about homelessness.

I’m often asked if there is a public will in Los Angeles to do anything about homelessness.

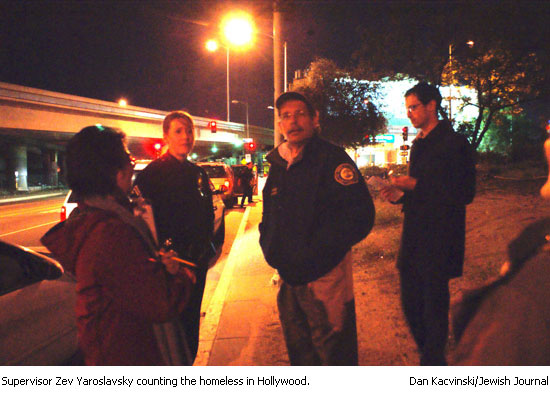

The answer came through loud and clear last week when more than 200 volunteers showed up in Hollywood for the biennial homeless count in Los Angeles County. Those of us taking part in the Hollywood count were playing a role in a nationwide effort aimed at identifying the number and location of homeless persons living on the streets.

The purpose is simple: If we are going to address homelessness, we need to know where to target our limited resources. The homeless count gives us a road map to make a real difference on this vexing issue as we move toward a goal of providing permanent supportive housing to the chronically homeless—those who have been on the streets for at least a year.

All across the region last week, groups like ours assembled around 9 p.m. and got our marching orders for the night ahead. Each team was assigned a territory and given some simple rules of engagement: keep a respectful distance and don’t interact with the people you’re counting; use your flashlight to light up your tally sheets, not those you’re tallying; and use caution and common sense in navigating the streets at night.

I had lots of company out there. Thousands mobilized to help with the federally-mandated count, administered here by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Among the volunteers were members of my staff. I’d like to share a few of their impressions with you here.

One of my deputies joined the counters in his hometown of Santa Monica. He came across people living in cars in the parking lot of a busy family restaurant—a sight that might have gone unremarked during the daytime. He also was struck by the juxtaposition of wealth and poverty, such as the homeless pair encamped just 50 feet from a trendy Italian bistro where patrons drop $200 on a dinner for two with wine.

The night-time trek, he said, definitely made him see his city in a new way.

Another deputy, who had taken part in the Santa Monica count in 2008, noticed a marked decrease in the number of homeless people on the same blocks this time around. That may be the result of Santa Monica’s efforts with the county to provide housing along with the services necessary to address the issues that render people homeless in the first place.

This deputy was struck by the homeless prevention measures she saw in place: trash dumpsters fenced off and locked, bright lighting, locked apartment and condo garages off the alleys, and less accessible areas to loiter. Overall, the city seemed clean and shiny, which made it even more heartbreaking to see homeless people huddled on sidewalks in worn sleeping bags or torn-apart cardboard boxes.

In West Hollywood, one of our staff teams wondered what and who they would encounter in their assigned tract—which included landmarks as various as the Mondrian Hotel and Barney’s Beanery. Their night of surveying began and ended with the two people they observed huddled under a blue tarp in a drugstore parking lot. A sheriff’s deputy accompanying our staffers knew the pair well. He said they’d come out to California from the Midwest years ago, eking out a living by recycling. They’d had run-ins with the law over their methamphetamine use, he said, and so far had rebuffed offers of help from the agency PATH (People Assisting the Homeless.)

Another 3rd District team hit the streets in Van Nuys. One of their experiences illustrated a challenge inherent in our assignment: who exactly should be counted as homeless, based on sight alone? Was that man in the hooded sweatshirt homeless—or just someone walking aimlessly through the neighborhood? When our team spotted the same man 10 minutes later, this time pushing a shopping cart loaded with possessions, the question was answered. He became part of the tally.

It will be months until the final results of the count are in. But one thing is already clear: Last Thursday night, the main room at the old Hollywood Municipal Building was bulging with people, enthusiasm and commitment. Despite the difficulty of the task, the scene of hundreds of people participating in a homeless count into the wee hours of the morning provided a rousing answer to anyone who doubts our community’s commitment to addressing homelessness.

Posted 2/1/11

Counting on each other

January 6, 2011

Happy New Year to you all. Together, let’s start 2011 on the right foot—literally. Please join my staff and me for the bi-annual Homeless Count. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority needs 4,000 volunteers to hit the streets between January 25-27.

As you’ll see from this story on my website, the count is required for federal homeless funds to flow to counties and cities across the nation. Never before has there been a more determined commitment in the public and private sectors to end chronic homelessness by providing those in need with permanent housing and services.

Last month, the United Way of Greater Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce released a blueprint—called Home for Good—with the ambitious but achievable goal of ending chronic homelessness in five years.

And just this week, we were able to allocate nearly $1.7 million in Third District homeless funds to two organizations in the forefront of the growing movement to provide permanent supportive housing—Step up on Second and OPCC. For more details, read here.

So, I hope I can count on you to join this year’s Homeless Count and make a tangible difference in someone’s life.

A five-year plan to end homelessness

December 1, 2010

A growing number of business and political leaders in Los Angeles are rallying behind a plan that boldly promises to end chronic homelessness within five years—a plan that on Wednesday got an announced boost of $13 million from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation.

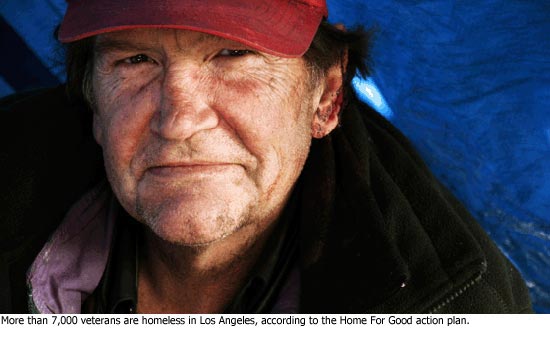

The plan, Home For Good, calls for a sweeping reorientation of strategies and expenditures in Los Angeles County for the chronically homeless and military veterans living on the region’s streets. The goal is to provide permanent, rather than temporary, housing to these individuals, who would then immediately have access to a stream of health and mental health services to help them restore their lives.

At the same time, according to the plan, taxpayers would be saved millions of dollars now being spent by the criminal justice and emergency health care systems to cope with the county’s huge homeless population.

“We need to shift the paradigm away from a system that has been cumbersome and confusing to an efficient system focused on finding people homes,” states the report, a joint initiative of the United Way of Greater Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce.

This model, known as “permanent supportive housing,” has taken root in cities across the nation, including Los Angeles, where a program called Project 50 on Skid Row has shown dramatic results.

At an event on Wednesday to publicize the Home For Good action plan, a number of Los Angeles’ top officials were on hand, including Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who initiated Project 50 and has backed its replication throughout his district and beyond.

During his remarks at the gathering, Yaroslavsky said that Home For Good “sets the record straight” that permanent supportive housing is the most effective approach to helping individuals who’ve been identified as the most likely to die on the streets.

Once these people are in a home—and a trusting relationship has been established—“we can open their minds and their hearts to the treatment they need, the services they need, so they can function in our society,” Yaroslavsky said. “In order to end homelessness, we’ve got to provide a home.”

Yaroslavsky’s comments were indirectly aimed at critics of the housing first approach, who argue that homeless individuals should not be given publicly supported residences unless they’re first receiving mental health care and substance abuse treatment.

That is not, however, the prevailing attitude among the unprecedented coalition of elected officials, business leaders, philanthropists, religious leaders and housing advocates who’ve endorsed the United Way/Chamber of Commerce initiative.

Permanent supportive housing also is the favored approach of the Obama Administration, as was made clear on Wednesday by Barbara Poppe, executive director of the U.S Interagency Council on Homelessness. She said the Home For Good blueprint could open the door to more federal funding. “It’s not enough to plan,” she said. “It’s only enough if we act.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas agreed, saying: “We must turn Home For Good into action. Measurable results, in the final analysis, is what matters.”

To help ensure that action, Steven M. Hilton announced that the Hilton Foundation would provide $13 million in grants, spread across three years, to fund key components of the campaign. The approach advocated by Home for Good “restores stability, autonomy and dignity and helps the individual integrate back into the community,” said Hilton, president and CEO of the foundation.

Hilton said that $9 million of grants will be given to the Corporation for Supportive Housing to spur the creation of 2,500 new permanent supportive housing units; $3.6 million will be used to identify and house 4,500 of the most vulnerable people on the streets. The rest will be distributed to other non-profit and faith-based efforts on behalf of the chronically homeless.

He called Los Angeles’ homeless problem “shameful,” and said that the homeless man on the street is “somebody’s son, father, brother. In effect, they’re one of us.”

Posted 12/1/10

Why Project 50 saves lives

August 2, 2010

If you want to solve homelessness in Los Angeles, you have to start on Skid Row.

I heard that observation voiced by a participant at a conference I convened in 2007. The words rang true to me then, as they do now. It is a simple declaration of a difficult fact: that Job One in fixing the national disgrace at the heart of downtown means trying some innovative tactics to begin alleviating some of the miseries endured by individuals on the street there.

The Los Angeles Times is now in the midst of a four-part series chronicling Project 50, the initiative that grew out of that conference. As the first story points out—and as the newspaper suggests in promoting the upcoming installments—it has been a difficult journey, with many hard-won successes and some disappointments along the way.

Project 50 is one of the most rewarding public policy initiatives I have ever sponsored. Its foundations were established at that 2007 conference, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. We brought people to Los Angeles from across the country—people who had successfully turned around homelessness in their own cities and counties. Before meeting with our policy makers and civil servants, these out-of-town participants toured Skid Row, and every one came away recommending that we start there.

Roseanne Haggerty, who runs Common Ground, a New York non-profit that deals with homelessness, suggested we launch a pilot that would identify the most vulnerable homeless people on Skid Row—those most likely to die on our streets. Then, we’d find them a place to live and give them the services they needed. In the language of homeless advocates, this is called permanent supportive housing.

Since we would be going after the most troubled people—the hardest cases who for years had resisted every program to come along—we needed to be innovative to reach them. So we broke with conventional practice and did not make it a precondition that participants accept services in order to get a roof over their heads.

But once we got them housed, our county and affiliated non-profit agencies had one, unified goal: to surround them with the health care, mental health care and substance abuse services they required.

It was a relentless mission. Once these clients moved in, our people were on them like a wet blanket, pushing to get them the help they needed.

And here’s the striking part: every single participant ended up agreeing to accept at least one kind of treatment.

What has evolved in the last 2 ½ years has been nothing short of remarkable. Project 50 has actually housed 68 homeless persons, most of whom had health, mental health and substance abuse issues. Many had been homeless on the streets of Los Angeles for more than 10 years; one had been homeless for 37 years. These were the most challenging of the challenged homeless persons in our county. And because of Project 50, we were finally able to break through—not to all, but to a very substantial majority.

Since 2008, nearly 84% of those we housed remain housed, a statistic which has left in tatters the myth that we can’t get chronically homeless persons into housing. And 100% of the clients have received one or more of the health care, mental health or substance abuse treatments they desperately needed.

A collateral benefit is that this pilot has been a money saver as well—a point recognized by the Economic Roundtable and others. The cost of running this program is more than made up by the savings realized by the relative stability that has been restored to our clients. Before Project 50, most of its participants landed in jail or in hospital emergency rooms multiple times each year. Since being in the program, most have avoided incarceration or hospitalization at a considerable financial savings to taxpayers.

And when progress is measured in human lives saved—lives that almost certainly would have been lost on the streets without Project 50—that represents a success well worth celebrating and replicating.

Project 50 has rapidly expanded beyond Skid Row to other parts of the county. Nearly 400 permanent supportive housing units are in the pipeline in West L.A., Van Nuys, Venice, Santa Monica, Hollywood, West Hollywood and Long Beach. Other communities have expressed serious interest as well.

Los Angeles has often been called the homeless capital of the nation, and one could hardly argue with that moniker. It can be very daunting to try to address the housing and service needs of well over 10,000 chronically homeless people in our county. That’s why dealing with them 50 or 500 individuals at a time made so much sense to me. Project 50 established the template. The same methodology that was applied to housing 50 chronically homeless can be applied to 500 or 5,000.

Thanks to this project, and its courageous and dedicated county employees and their non-profit partners, we are on our way.

Posted 8/02/10

L.A. Times columnist Steve Lopez has weighed in on Project 50, praising its hard-won successes for the chronically homeless on Skid Row as “no small triumph.” Read his column here. And our article on the Project 50 debate that cropped up at last week’s Board of Supervisors meeting is here.

New funds for Westside homeless agencies

July 13, 2010

Federal housing officials last week awarded more than $4.7 million in housing subsidies to three Third District non-profits that are developing cutting edge programs to house the chronically homeless.

The winners of the competitive “Shelter Plus Care” grants were the Venice Community Housing Corporation, Step Up on Second and Ocean Park Community Center, or OPCC.

The grants from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Department provide apartment rental subsidies, or vouchers, for a five-year period. To qualify, the providers must match the value of the vouchers with spending on health care, case management or other services.

All three winning organizations are committed to the concept of permanent supportive housing—combining long term residences with customized health care and social services for homeless people with the greatest risk of dying on the streets. In Los Angeles County, this approach is the hallmark of the successful Project 50 on Skid Row. Since then, programs based on Project 50 have spread to Santa Monica, Venice, Long Beach, West Hollywood and Van Nuys.

“People are homeless because they have underlying problems that, if not addressed, will keep them homeless,” says Howard Katz, a commissioner with the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which will distribute the new funding. “These three organizations have shown that they understand this relationship and know how to effectively address it.”

In addition to the three grants to non-profits, the City of West Hollywood received $1.25 million and the County’s Department of Mental Health $4.13 million in Shelter Plus Care funding.

Here’s how executives of the Third District non-profits say their organizations—and their homeless clients—will benefit from the infusion of rental subsidies:

Steve Clare, executive director of the Venice Community Housing Corporation, which provides housing and services to low income individuals. The organization received $1,133,220.

Steve Clare, executive director of the Venice Community Housing Corporation, which provides housing and services to low income individuals. The organization received $1,133,220.

“That money will allow us to house 20 homeless people with disabilities who have essentially no income. They’ll live at a new project of ours. It’s called Horizon Apartments, and it’s a 20-unit building we’re renovating that’s located a half block from the beach. It’s a beautiful building; it used to be a short-term tourist hotel and it needs relatively little renovation. We hope we’ll have the building ready next winter. The residents will receive case management and other services, and we’ve contracted to provide mental-health services. We have the building and the services lined up, but the rental subsidy this grant provides is critical. Without it, we’d have to be charging residents $800 or $900 a month per person to cover our basic operating costs. The project would be impossible.”

John Maceri , executive director of OPCC, a Westside provider that operates shelters and “housing first” programs for the chronically homeless. The organization received $1,659,900.

John Maceri , executive director of OPCC, a Westside provider that operates shelters and “housing first” programs for the chronically homeless. The organization received $1,659,900.

“The award is for 40 vouchers and it’s an enormous boost to our ability to house people. It allows us to continue to expand our services to more of the at-risk homeless who have the most to lose by remaining on the street. Ours is a scatter-site application, meaning that we find apartments for clients all over the area, not in a particular building. We already have about 300 units now. We’ll be working with chronically homeless single adults living with multiple disabilities, from mental health to substance abuse issues and chronic health problems. About 35 percent of the folks we serve are seniors. The length of time on the street ranges from six to 30 years, with the average at 12 years. We have staff who will be intensely involved helping the new clients locate units. I hope we’ll have a start date in the fall.”

Tod Lipka, chief executive of Step Up on Second, a Santa Monica mental health provider, which is launching a new Step Up on Vine project in Hollywood. The organization received $1,980,300.

Tod Lipka, chief executive of Step Up on Second, a Santa Monica mental health provider, which is launching a new Step Up on Vine project in Hollywood. The organization received $1,980,300.

“We’re converting a three story motel on Vine Street into a 34-unit permanent supportive housing facility for homeless people living on the streets of Hollywood. We acquired the building in August 2009 for $3 million. Our timetable is to begin construction in June 2011 and open in June 2012. We’ll be housing chronically homeless people with mental health disabilities. It’s typically schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression. All of these people will be very low income. The vouchers…are really necessary to cover the gap between the small amounts the residents can pay, which is 30 percent of their income, and the actual operating costs. We’re going to provide ongoing support because housing is a big transition for people who have lived on the streets long-term. As one of our clients said, ‘Getting housing is just the first step’.”

Posted 7/13/10

Hope on the streets of Hollywood

May 3, 2010

My alarm went off at 3:00 a.m., rousing me from bed for a trip to Hollywood to participate in a new count of homeless people—one in a series of such surveys conducted in Skid Row and throughout my supervisorial district during the past 2 ½ years.

My alarm went off at 3:00 a.m., rousing me from bed for a trip to Hollywood to participate in a new count of homeless people—one in a series of such surveys conducted in Skid Row and throughout my supervisorial district during the past 2 ½ years.

The purpose of this count, like the others, was to identify as many homeless people as possible and determine who among them is most likely to die on the streets unless they’re given the services and housing they desperately need. Each individual is asked a series of scripted questions about their health, mental health, substance abuse, economics or any combination of the above.

At the end of this week’s three-day Hollywood survey—conducted under the guidance of Common Ground, a New York-based non-profit that pioneered this technique—a list will be turned over to the county and its service providers. We then will begin the delicate and difficult process of convincing these vulnerable individuals to accept our offer of housing and services.

The team I joined on Monday covered an area bounded by La Brea, Highland, Franklin and Sunset. Our team leader was a highly motivated and passionate intern from People Assisting the Homeless (PATH) by the name of Alex Cornell, who is pursuing a divinity degree. We were told we needed to complete our survey before sunrise, in the hours before the homeless would begin to scatter for the day.

In the pre-dawn chill, in the shadow of boutique hotels and gentrified storefronts, we found people asleep on church steps, in parks and on bus benches. Alex gently approached each of our prospective clients and asked if they’d cooperate in answering the questionnaire. As an inducement, they were offered a $5 coupon from Subway sandwiches. While most agreed to participate, some wanted only to be left alone, despite our offer of food.

I have to confess that I had not planned to spend the whole 2 ½ hours on the streets of Hollywood in the middle of the night interviewing the homeless. But once I got started, I couldn’t stop. With each person we interviewed, I felt a sense of responsibility to them and an even greater sense of the possibilities we could offer to help avert a tragic end to their lives.

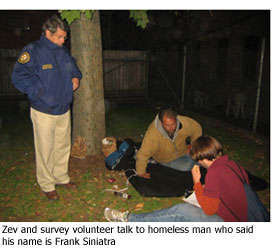

The first man we found was sleeping in a pocket park off of Franklin Avenue. He’d been homeless for 8 years, most of them in Hollywood and most of them in that park. He said he’d suffered a traumatic brain injury in an accident some years ago and had no memory of anything. His name, he said, was Frank Sinatra. I suspect he’ll end up on Common Ground’s “vulnerability index” as one of the homeless who’ll rank among the area’s most likely to die on the streets without services and housing.

As we walked down La Brea Ave. between Hollywood and Sunset, we found a man in his late 50’s sleeping on a cot in the front yard of an apartment building. He offered a different face of the problem of homelessness on our streets.

Homeless for two months, he said he has a B.A. from UCLA and was honorably discharged from the United States Navy. I asked what precipitated his life of homelessness in Hollywood. He said that he’d been living with his mother in Altadena when her failing health forced her to move into a convalescent hospital. To pay the costs, she needed to sell her house, leaving her son without a roof.

One of our other teams found a colony of homeless people living in the hills above the Hollywood Bowl—more than 20 of them led by their “mayor,” an armed forces veteran who has been homeless for more than two decades. One of the tragedies of homelessness in our country is that somewhere between 20% and 25% of the homeless are veterans of our armed forces. They answered the call of our nation, and now it’s time for us to answer their call for help.

That’s what the Hollywood homeless count is all about. We’ve already had success with this approach in Skid Row, in Venice, in Santa Monica and in other communities, where “permanent supportive housing” will be provided in the months ahead to nearly 500 of the most chronically and vulnerable homeless on our streets.

These are the individuals who’ll end up in our jails and emergency rooms multiple times during the course of a year if they’re not housed and provided with crucial health and mental health services. On the streets, they run up a fortune in health and incarceration costs. Providing them with permanent supportive housing will actually save our county and society money because these individuals will no longer end up in jail or in emergency rooms with anything approaching the same frequency.

I know that the magnitude of our homeless problem can seem intimidating and insurmountable. But this is a problem of individual lives, not statistics. Common Ground’s “vulnerability index” gives us a biography of sorts for each of these people, giving us new and deeper insights into their struggles and exactly what they need to have lives restored. Our job is to take those biographies—those life stories—and change their trajectories.

To see a video of Zev addressing homeless volunteers before heading onto the streets, click here.

Posted 4-29-10

Read related story

Meet Kerry Morrison, who represents Hollywood business and organized the homeless count.

Embracing the Hollywood homeless

April 29, 2010

“I’m Kerry, what’s your name?”

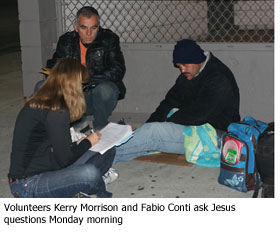

It’s 4:30 a.m. on Monday, and Kerry Morrison, a Hancock Park mother of two teens, stops a limping man named Vicente at a Chevron station on Highland Avenue in Hollywood. The tall woman with the clipboard is calm, friendly and matter of fact.

“I want to ask you some questions about being homeless.”

With a bit of sweet talk—and a free meal card from Subway—Morrison cajoles Vicente to share his saga of street life, which includes frostbite, substance abuse and jail time.

“I’m so happy that this is finally happening,” Morrison says walking down Hollywood Boulevard after speaking to Vicente. “We need to do everything we can to humanize the homeless.”

Morrison is one of more than 50 volunteers collecting data for the Hollywood Homeless Registry, a three-night survey that marks the first detailed study of the full homeless population in that area.

She’s also the driving force behind the whole effort.

Morrison, 54, is executive director of the Hollywood Entertainment Business Improvement District, a band of 250 business owners working to improve economic and quality of life conditions on Hollywood Boulevard. She’s worked for more than two years to bring together non-profits, government and business groups in a coalition called Hollywood 4WRD to help end the neighborhood’s longstanding homeless problem.

“Kerry’s been the hub,” says Fabio Conti, owner of Fabiolus Café on Sunset Boulevard who brought jackets and blankets to hand out to the homeless. “She’s the happiest lady in the world when she’s talking to these people.”

Beth Sandor, field director in Los Angeles for Common Ground, a homeless advocacy group that developed the four-page “vulnerability index” questionnaire used in the survey, praised Morrison as “one of the most committed business leaders in Los Angeles on the issue of ending homelessness.”

The purpose of Common Ground’s 38-question survey is to identify those most likely to die on the streets and provide them with housing and comprehensive medical, mental health and social services. The questions focus on factors such as the number of recent emergency-room visits, jail stints, substance abuse problems and chronic illnesses.

The vulnerability index was instrumental in the creation of Project 50, the groundbreaking program launched more than two years ago at the urging of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky that has housed and provided services for 66 once-chronically homeless individuals on L.A.’s Skid Row. That program has now been replicated in other parts of Yaroslavsky’s district, including Venice, Santa Monica and Van Nuys.

Before the pre-dawn launch of the Hollywood effort, the supervisor spoke to the survey volunteers and then headed onto the streets with them. By Wednesday afternoon, questionnaires had been completed for 257 homeless men. Another 70 declined to participate. More than 82 percent of the Hollywood homeless were men, whose ages ranged from late teens to a newly-homeless man of 80.

Before the pre-dawn launch of the Hollywood effort, the supervisor spoke to the survey volunteers and then headed onto the streets with them. By Wednesday afternoon, questionnaires had been completed for 257 homeless men. Another 70 declined to participate. More than 82 percent of the Hollywood homeless were men, whose ages ranged from late teens to a newly-homeless man of 80.

Morrison once seemed like an unlikely champion for Hollywood’s homeless. Raised in a middle-class Denver suburb, the daughter of a steel salesman, Morrison worked in government affairs at the California Association of Realtors for over a decade after moving to L.A. in the late 1970s.

Jolted by the 1992 riots to aid in the city’s recovery, she became executive director of the new Hollywood business improvement district, and came face to face with the neighborhood’s homeless problem.

As Hollywood worked to gentrify, some business owners—and many residents—hoped the solution to the homeless problem was simply to move the street people out. Morrison disagreed and vowed to educate herself and her board members.

She came to prefer the “permanent supportive housing” model, in which individuals are given apartments along with a variety of services to help them lead more stable and healthy lives. Her view was far from prevalent. When a 60-unit project was proposed for Gower Avenue in 2006, the backlash stunned Morrison.

“The community vitriol was mind-boggling,” she recalls. To this day, the project remains on hold.

In 2008, Morrison invited then-President Bush’s homeless czar, Philip Mangano, to make the case for permanent supportive housing as a better solution than shelters for the urban homeless. Later, she organized a field trip to visit Step Up on Second’s permanent supportive housing facility in Santa Monica. She put together a “snapshot” count of Hollywood’s homeless that year that found about 500 people living on the streets.

As part of her education, Morrison also realized she needed to get closer to her homeless neighbors. “I made a commitment to start talking to homeless people,” she recalls. “I had to conquer my own fears.”

She befriended local street people, including a mentally-ill man named Torrey who slept along the Walk of Fame until Morrison pushed for his hospitalization. He now lives in a Hollywood motel, although he declines to take his medication, Morrison says.

The experience taught her that it was essential for business owners and the public to see the homeless as people with individual stories.

That’s why the Hollywood team will take the unusual step of announcing the names and profiles of the 10 most vulnerable among Hollywood’s homeless at a news conference at 2 p.m. Friday at the Los Angeles Film School, 6353 Sunset Boulevard.

“We know that getting housing for them won’t happen unless we put the names and faces to the issue,” Morrison says.

The problem, Morrison notes, is that there aren’t yet apartments and housing in place for these individuals. Step Up on Second has bought a motel on Vine Street for permanent supportive homeless housing, but construction has yet to get underway. A committee is working to identify other housing possibilities, Morrison says.

She hopes publicity from the survey will lead to housing breakthroughs. She notes happily that Los Angeles City Councilman Tom LaBonge and two staffers joined the survey Tuesday morning and hopes he and other city leaders will come through with help on the housing front.

“The survey is an essential step,” says Morrison. “I’m incredibly optimistic that Hollywood can be a community that can embrace the homeless.”

Posted 4-29-10

Read related story

On his blog, Zev writes about his night with the Hollywood homeless.

Project 50: watch us grow

October 15, 2009

Call it “Project 250.”

Spurred by the success of Project 50, the paradigm-busting homeless program targeting Skid Row’s most vulnerable residents, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky earlier this year proposed a countywide expansion he dubbed Project 500. But when the full Board of Supervisors asked the Auditor Controller to further study the program’s benefits before committing, many observers guessed that the expansion was on hold.

Not exactly.

Without fanfare, similar county-approved homelessness projects in three Third District communities are already well underway, working to house 130 in Santa Monica, 40 in Venice and 30 more in Van Nuys. Together with the initial 50 clients in downtown L.A., you might say Project 500 is halfway home.

The newer projects follow similar protocols pioneered in downtown Los Angeles by Project 50, an innovative initiative shepherded through the board by Yaroslavsky that is now in its second year.

Outreach workers identify the most at-risk homeless based on a “vulnerability index” created by New York City-based homeless advocates Common Ground. The index assesses such factors as recent hospitalizations, arrests, addiction issues and length of homelessness. Those in gravest danger of death are placed in permanent supportive housing, surrounded with health and mental health services, along with substance abuse treatment, that can revitalize lives and save taxpayer’s money in reduced jail time, hospital stays and emergency room visits.

During its first year, Project 50 reported encouraging results (see Power Point here). Among other things, those results suggested that the chronically homeless are not “service-resistant” and want to move into housing. Eighty-eight percent of the men and women recruited at the beginning of the program remained in housing at the end of the year, despite the fact that they’d averaged nearly 10 full years living on the streets before signing up. Thirty seven of the 39 in the group diagnosed with mental illness were receiving treatment, and 61 percent of the substance abusers had entered counseling.

Preliminary cost data showed substantial savings, too. Hospital and emergency room visits plunged for the group compared to the previous year, as did jail time, saving taxpayers more than $500,000, according to preliminary figures. Project 50 has been allocated $3.6 million in county funding.

The new programs:

Venice: St. Joseph Center of Venice, which identified the community’s most vulnerable homeless individuals during a three-night survey in May, has signed up 28 of the 40 clients it hopes to house in its two-year program, according to Va Lecia Adams, the center’s executive director. One of those is Gigi Davis, 51, a Marine Corps vet who has been sleeping on the streets near the Venice post office and says she is bipolar and has a drinking problem. Now taking psychiatric medications, she says she is grateful “for the improvement in my day to day life that I’m already seeing.”

Santa Monica: Five providers are combining to house 130 of the area’s most vulnerable homeless people, first identified in a survey nearly two years ago. The Ocean Park Community Center is serving 40 individuals, and Step Up on Second is working with 30. The other clients are working with the Clare Foundation, St. Joseph Center and the Veterans Administration. Tod Lipka, Step Up on Second’s CEO, noted that a recent homeless census showed a first-ever drop in this population, boosting confidence that homelessness can be successfully attacked. Such programs, Lipka, says go “a long way to address the problems of homelessness.”

Van Nuys: Following a homeless survey in May in Van Nuys, the San Fernando Valley Community Mental Health Center will be combining services for 30 clients over the next year. Program director Anita Kaplan says 13 clients have been enrolled and will get Section 8 housing vouchers as they become available. “This fast-track into permanent housing is definitely unique,” says Kaplan. “I do see a lot of successes.”

Read L.A. Times columnist Steve Lopez’s take on Project 50.

Posted 10/15/09

Project 50

April 7, 2009

A groundbreaking pilot program aimed at helping Skid Row’s fifty most vulnerable and chronically homeless individuals has concluded its first year with a series of encouraging results that hold promise for a dramatic expansion of the effort.

Initiated by Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the Project 50 program draws upon an unprecedented collective of government and private agencies to provide permanent supportive housing, medical assistance, mental health counseling, substance abuse treatment and other vital services to individuals facing the greatest chance of death on the street.

Eddie Givens, formerly known on Skid Row as "Wild, Wild West," is one of Project 50's early success stories. Pictured here before and after he was recruited into the pilot program.

Participants were identified through a massive outreach that ranked them based on their risk of mortality. The first-year results—provided during a February 4th briefing of more than 100 homeless services professionals from the public and private sectors—suggested that not only were most of the targeted individuals faring better but that the broader public was benefiting as well.

Among other things, the program preliminarily suggests that the chronically homeless are not “service-resistant” and want to move into housing and that intensive medical care and drug abuse services save tax dollars that would otherwise be spent on emergency room visits and jail.

In light of the encouraging findings, Supervisor Yaroslavsky set a goal for Project 50’s second and final year to increase the ranks of participants to 500 from throughout the county.

Here’s a Project 50 PowerPoint that provides deeper details of the program.

See news coverage here:

Steve Lopez, “Smart Spending Skid Row Program,” Los Angeles Times

Daily News, “Skid Row Residents Now in Housing”

Downtown News, “Project 50 May Grow”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink