The ballerina takes a bow

December 11, 2009

As thoughts turn to the visions of sugarplums that spice up the holiday ballet season, Yvonne Mounsey stands—regally, of course—for the grace and fortitude behind the glitter.

The acclaimed ballet instructor and former ballerina wears the mantle of her 90 years so lightly that she virtually bounded up to the dais recently to receive special birthday honors from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and his board colleagues. With her ageless vitality (not to mention her envy-inspiring posture), Mounsey graciously acknowledged the tribute. “I really love what I do, and have been doing for so many years, and hope to continue to do what we do for ballet, particularly in Los Angeles,” the dancer explained simply.

The journey from international dancer to Westside ballet doyenne was anything but simple. Consider the person behind the proclamation:

A native of South Africa, Mounsey found her artistic calling at an early age. In 1949, after more than a decade of work in several ballet troupes that carried her to varied locales on the Continent, throughout North America, Central America, Cuba and Australia, legendary choreographer George Balanchine recruited her for his fledgling New York City Ballet. There, she performed as a soloist and later principal dancer in memorable roles such as the Siren in Balanchine’s “Prodigal Son” and many others before returning to South Africa in 1960 to co-found the Johannesburg Ballet.

Later, she relocated to Los Angeles with her husband and daughter. In 1967, she took over a struggling dancing school and formed an enduring artistic partnership with former Royal Ballet dancer Rosemary Valaire. Together, they established the Westside Ballet, today one of the West Coast’s most esteemed ballet academies.

“We present performances of the Nutcracker every year and the spring performance, at reasonable prices so all the children can come and see us,” Mounsey told the Board, “so that’s our aim, is to give ballet and the arts to the children.” That she has done for more than seven decades, and the world of dance is richer for it.

Watch Dance TV’s earlier birthday tribute here, and learn more about the Westside Ballet here.

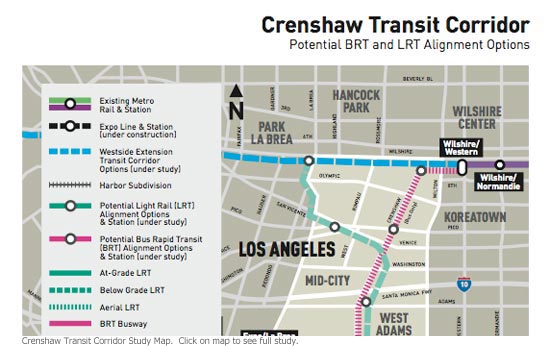

Board votes unanimously for Crenshaw Boulevard transit project

December 10, 2009

The Crenshaw Boulevard transit project moved closer to reality Thursday as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board voted to build the project as a light rail line and to officially dub it the Crenshaw/LAX Transit Corridor. The board’s unanimous vote, during a lively session before a standing-room-only audience, sends the project into the final environmental review phase.

The project will be financed by Measure R funds, the half-cent sales tax that was approved by county voters last year.

For a full report, go to Metro’s blog, The Source.

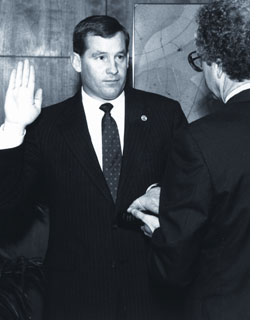

Ordin slated to become first woman county counsel

December 10, 2009

Andrea Sheridan Ordin, one of Los Angeles’ biggest legal names, who has served as a pioneering federal, state and local prosecutor, is poised to become L.A. county’s top lawyer.

Next Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors is expected to hire Ordin as its next County Counsel—the first woman to hold the position. She would oversee a staff of more than 250 lawyers who provide a diverse range of legal services to the supervisors and county departments.

Ordin, at a salary of $295,000 a year, would replace acting County Counsel Robert Kalunian, who took the position on temporary basis in April, after the retirement of the long-serving Raymond Fortner.

Ordin, at a salary of $295,000 a year, would replace acting County Counsel Robert Kalunian, who took the position on temporary basis in April, after the retirement of the long-serving Raymond Fortner.

For Ordin, currently vice chairman of the Los Angeles Police Commission, the L.A. County position would represent the latest in series of high-profile, and sometimes groundbreaking, government jobs.

Back in the mid-1970s, then-District Attorney John Van de Kamp named Ordin as the first female assistant district attorney, the office’s third highest job.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter named Ordin as U.S. Attorney for the Central District of California, based in Los Angeles, where she also was the first woman to hold that post. She served for four years, supervising all of the office’s criminal and civil litigation.

In 1983, Van de Kamp, who was then California’s attorney general, tapped Ordin again, this time as chief assistant attorney general, where she oversaw litigation regarding civil rights, antitrust, consumer and environmental litigation. She served in that office until 1990.

“She’ll call them straight,” Van de Kamp said Thursday. “She’ll give you her best judgment as to what the law is regardless of partisan politics.”

Ordin also has been deeply involved in oversight of the Los Angeles Police Department. In the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, she was named to the Christopher Commission, which investigated the factors that led to the beating of Rodney King and subsequent uprising.

Christopher, reached for comment on Thursday, said in a statement: “Andrea Ordin has demonstrated a deep commitment to public service throughout her entire career, and with her deep knowledge of Los Angeles and fine legal skills, she will be a great asset to the County.”

In the book “Official Negligence,” author Lou Cannon credited Ordin with the decision to include blatantly bigoted and sexist police e-mail messages in the Christopher Commission’s report to help better capture the department’s internal culture and keep “the report from being an overly dry statistical analysis.”

In 2005, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa appointed Ordin to the Police Commission, the five member civilian board that oversees LAPD policy and practices.

Currently, Ordin is a litigation partner at the firm of Morgan Lewis, where she practices in state and federal courts. Her legal practice there is focused on environmental and business litigation as well as appellate work before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Newly hired planning director ready for big challenges

December 8, 2009

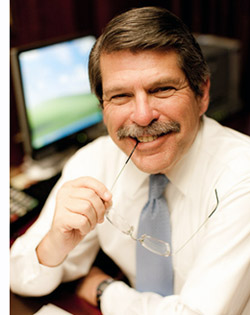

Richard Bruckner, who for the past 10 years has been Pasadena’s director of planning and development, on Tuesday was named Los Angeles County’s director of regional planning.

When he starts work Feb. 1, Bruckner will become the key architect of revamping the county’s general plan—a document that will chart the course for how Los Angeles County will look and function for generations to come.

Bruckner said his biggest challenge in his new post will be dealing with new state legislation on climate change—an effort that will require the close alignment of land-use and transportation planning decisions. He said the county job presents “the challenge of diversity and scale.”

“It’s certainly a step-up in scope,” he said.

“His experience in Pasadena over the past 10 years has been tremendous,” said Katherine Perez, executive director of the Urban Land Institute’s L.A. District Council. She credited Bruckner, who is one of two public sector members of the institute’s executive committee—with the skillful implementation of Pasadena’s general plan.

“It’s Richard’s nature to be collaborative. It’s Richard’s nature to work in partnership,” Perez said, adding that he was skillful in bringing together diverse constituencies such as community stakeholders, business developers and transit planners in Pasadena.

He also has a broad network of relationships in planning and redevelopment circles across the state and commands respect because of Pasadena’s reputation as a well planned city in which community-driven processes play a big part.

Pasadena Mayor Bill Bogaard said Bruckner has been “highly influential in the city’s planning and development” over the past decade, and said he had deftly handled development and community implications of the Gold Line light rail coming to town.

As for high points of his Pasadena tenure, Bruckner pointed to accomplishments such an ordinance requiring developers to provide moderate- and low-income housing; updating plans to integrate housing and transportation in the city’s Old Pasadena and Lake Avenue districts, and setting aside 20 acres of “very important hillside habitat” in Annenberg Canyon.

The county position has been open since the departure of Bruce W. McClendon about a year ago.

As the county’s chief land use planner, Bruckner will earn $210,000 annually. His hiring was recommended by Los Angeles County Chief Executive Officer William Fujioka and approved by the Board of Supervisors.

Multi-million dollar loan has LA Opera singing a happy aria

December 8, 2009

The operatic repertoire is full of passion, suspense and dizzying turns of fortune—kind of like what’s been going on at LA Opera, which is fending off financial uncertainty even as it gears up for its most ambitious year ever.

Los Angeles County stepped onto center stage in the hero’s role on Tuesday, guaranteeing a $14 million loan to keep the opera afloat.

“We are absolutely thrilled that the County of Los Angeles has recognized the important and prestigious role that a world-class opera company plays in our community,” said Plácido Domingo, LA Opera’s general director. The board’s support, he said, “will enable us to continue as a prominent and vital element in the cultural life of Los Angeles and in furthering this region’s stature as an international cultural center.”

The cash infusion will keep the opera going through June, 2012, when the company expects to repay the loan from more than $30 million in pledges made since June by donors responding to the opera’s urgent fundraising plea.

“They’re passionate and they put their money where their mouth is,” Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said of opera fans. As a result, the new financing arrangement carries “very minimal risk,” Yaroslavsky said, adding that the alternative simply is unacceptable. “This is one of our major tenants at the Music Center,” he said. “If they go, it sets off a chain reaction of events that could topple the Music Center.”

The financial crisis, coming at a crucial time in the 25-year history of the LA Opera, is not unique to this company, said Music Center CEO Stephen D. Rountree, who during the past year has also been serving as LA Opera’s chief financial officer. “Opera companies are always pressed but [LA Opera] had their operations in order until the recession hit,” Rountree said. “Ticket sales are down across the country.”

For example, the Washington National Opera, which also has Domingo as general director, recently announced cutbacks in staff and programming.

The LA Opera also has been scrambling to dig out of its deficit, cutting staff by 20% and administrative costs by 22%, Chief Executive Officer William Fujioka said in his letter to the board. “It also reduced the number of productions in its 2008-2009 season from 9 to 6, and gave fewer performances—48, instead of 67.”

Fujioka said the new loan arrangement “does not put the county in jeopardy whatsoever.” The county will issue bonds that will be purchased by a single financial institution, Banc of America, Leasing & Capital, LLC, which will then provide the money to LA Opera. The county itself is not putting up any cash but is guaranteeing the loan in the unlikely event that the opera’s anticipated donations fall through—something opera and county officials say as highly unlikely.

Rountree said that having Domingo—“the leading spokesman for opera in the world”—in Los Angeles, has proved invaluable in raising the donations. The county stepped in to assist in a similar manner during the construction of Disney Hall, until private donations could bridge the funding gap.The opera company, whose musical director is James Conlon, is gearing up for performances in June of the Ring Cycle, the four operas that comprise Richard Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen.” The operatic masterwork is at the heart of the 10-week Ring Festival LA, which begins next April and is expected to draw international attention with its broad range of musical performances, art exhibits and seminars.

And on that point, art is poised to triumph over money.

L.A.’s big green secret

December 7, 2009

Something remarkable is unfolding in the mountains above our urban sprawl — something for the ages. Parcel by parcel, acre by acre, we have amassed more protected open space than any major metropolis in the nation.

Something remarkable is unfolding in the mountains above our urban sprawl — something for the ages. Parcel by parcel, acre by acre, we have amassed more protected open space than any major metropolis in the nation.

Government sometimes deservedly gets a good knocking for its failures, for too often letting intergovernmental rivalries derail the best of intentions. But every so often, it’s important to take stock of successes that can temper the cynicism and restore a sense of civic idealism.

The story of the Santa Monica Mountains is one of those, one that has been told only in bits and pieces spread across the years. It’s a textbook example of collaboration between federal, state and local officials who worked hand-in-hand with grassroots groups dedicated to protecting the area from the kind of development that overtook the Hollywood Hills.

For me, the preservation of the Santa Monica Mountains is both political and personal.

As a young boy growing up in Boyle Heights on the Eastside, my family would pack us up for weekend picnics in Griffith Park. I’d hike, play football and experience wilderness just minutes from the grit and congestion of my neighborhood. In the park, it seemed I could breathe easier.

I carried those memories into elective office. As a member of the Board of Supervisors, the Santa Monica Mountains were in my district. It was now my responsibility to build on the legacy of my predecessor, Ed Edelman, who with former Rep. Anthony Beilenson and the late LA City Councilman Marvin Braude, championed the preservation of open space.

Over the decades, we have pursued two tacks.

One is to restrict the scope of development. Yes, property owners do have the right to build but they do not have the right, for example, to shave off gorgeous ridgelines to maximize panoramic views from their mansions. In other words, the terrain must dictate the development, not the opposite, despite the arguments of high-priced lobbyists and lawyers for developers.

The second approach has been to acquire parcels from willing property owners largely with funds approved for this purpose by voters. To that end, in 1997 we created a matrix we called “The Big Picture,” which identified parcels ripe for protection based on whether they contained ridgelines, creeks or wildlife corridors. Then we made a beeline for them.

I’m proud to report here that almost every high-priority property on our list has now been taken off the table, purchased by a consortium of county, federal and state agencies, including the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy.

No property better exemplifies what we’ve been able to accomplish than the $34 million acquisition of King Gillette Ranch, off Mulholland Highway near Malibu Canyon. At one point, the spectacular 600 acre property was on its way to becoming the stomping grounds of 5,000 students as part of a proposed expansion of Soka University.

In a private meeting that never made it into the headlines, I’ll never forget the extraordinary scene of representatives from federal, state and county government sitting around a table pledging millions of dollars so we could hit the purchase price. The magnitude of our task dwarfed our individual affiliations. We were of one mind.

Now plans are underway to transform King Gillette Ranch into a gateway for the Santa Monica Mountains recreation area, complete with a visitors’ center for those who’ll be enjoying the mountains long after we’re gone. Still, our work is not done. Next year, a state water bond issue is slated to come before you with funding set aside for more acquisitions. You know how I’m voting.

All of this, of course, is about more than a hike in the park. The protection of open space has become an environmental imperative in reducing the impact of air pollution and global warming. The Santa Monica Mountains have been called “the lungs of LA,” consuming carbon dioxide and cleaning the air. In fact, one of California’s strategies in meeting global warming mandates is to preserve natural land.

Now, let’s head back to Griffith Park.

For more than a decade in the late 1800s, the Los Angeles City Council balked at accepting Colonel Griffith’s generous but seemingly odd donation of rugged land on the far outskirts of the city. Year after year, the local officials asked why in the world they would want responsibility for it. What good was it anyway?

Thankfully, we know the answer to that. Griffith Park is a crown jewel of our urban life, surrounded, but not enveloped, by buildings and freeways. The park was there for me as a youngster, as it was for my children and, perhaps some day, for theirs, too. Today, we’ve helped ensure that, no matter what development awaits the region, the Santa Monica Mountains will be unscathed and unscarred.

And that’s something remarkable.

County fire chief says he enjoyed the ride but it’s time to go [updated]

December 3, 2009

Considering when to step down, L.A. County Fire Chief P. Michael Freeman thought about a white-water raft trip.

You can ride the raft too long, enticed by the prospect of more rapids around the bend. Or you can navigate to a calm spot and step ashore, making sure you don’t rock the boat for those still on board.

Freeman thinks he’s found that calm spot. Last month, the chief, 64, announced he’d be leaving in March from a job he’s held since 1989. That makes him the second longest-serving L.A. County fire chief—an almost unheard-of tenure for the top firefighter of a large urban area.

“Twenty-one years is a good run,” he said in an interview this week. “I think the organization would benefit by someone new stepping in.”

Freeman believes he’s leaving the 4,400-person department when “things are stabilized for a good period of time,” allowing Supervisors to pick his successor calmly and deliberately. By announcing now, he’ll be leaving between fire seasons, with the department’s $970 million budget in relatively good shape for the next few years. “I think we’re as stable on this white water raft as we can be,” he said.

That said, Freeman hasn’t been shy about roiling the waters on his way to retirement. In the aftermath of this summer’s Station Fire—the county’s largest ever—he bluntly called for reforms in the way the U.S. Forest Service fights fires in the Angeles National Forest.

All told, the Station fire incinerated 250 square miles, destroyed 96 homes and claimed the lives of L.A. County Fire Captain Ted Hall, 47, and Specialist Arnie Quinones, 34, who were trying to find an escape route for inmates at a fire camp—“very much of a personal loss that I feel and that all of the firefighters feel.”

Among other things, Freeman publicly urged the Forest Service to allow more night flights of firefighting aircraft on federal lands. He said such a practice is routine for county choppers on state or county land, weather permitting. He also proposed that helicopters and planes controlled by federal rules be allowed to fly at dawn to take advantage of the higher humidity and lower winds.

Freeman knew his proposed reforms might cause bad blood with federal officials and fuel public anger that had built over the lack of nighttime firefighting, which was being partially blamed for the blaze’s toll. But, Freeman said, “I felt that I had a duty and a responsibility to take a good hard look at everything about the fire.”

Based on a November report from Freeman, the Board of Supervisors last week asked Congress and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (the Forest Service’s parent department) to implement his recommendations. This week, the Forest Service announced it will review its fire-fighting policies in the national forest, including the night-flight restrictions.

Looking back over his career in Los Angeles, Freeman is proud of what he sees as the department’s gains in firefighting expertise, equipment and growth. He’s also overseen the broad expansion of paramedic services, including more airlifts and specialized services to stabilize patients on the way to emergency rooms and trauma units.Raised in Texas and hired after 24 years in the Dallas Fire Department, Freeman says he faced a “steep learning curve” when he arrived as the only outsider ever hired as an L.A. chief. He says hiring an insider would ease the transition for his successor. Declining to name names, he said there are “absolutely are viable, capable candidates inside the organization” and that a nationwide search is unnecessary.

Freeman knows that he’s going to miss the day-to-day camaraderie of the department. The emotional payoff will be tough to match, too. “I get a lot of satisfaction out of dealing with an ongoing series of challenges in a relatively orderly fashion.”

During his two decades at the top of the organization, Freeman gained a reputation as a hands-on boss, a micro-manager in the view of some in the department. Freeman jokingly described his management style as “hellish.” But he said he limits his tendency to “get down in the weeds” to key areas. He said he pays very close attention to “critical issues” with broad impacts, as well as to situations the department hasn’t previously faced. He said he also jumps in when he thinks his managers’ “strategic view is too short-sighted” after they propose solutions that may fix one problem but create another.

Given his energy, few people expect Freeman to morph into a quiet retiree. He said he won’t take another job or wile away afternoons on the golf course (“I don’t like golf, and I don’t want to start playing now,” he explained.)

But look for him to devote more time to the Catholic Church in his Whittier parish, where he’s a deacon. He’s got a grandchild due in January, and said he’d like to split time between L.A. and a house he and his wife bought north of Dallas.

After all those years of late nights and emergency calls, he vowed to “find a little different pace” by being home in the evenings with his wife of 41 years, Cathy Freeman. In fact, he said, “last night, we actually did eat together.”

It’s a good start.

[Updated 12/22]

Uh, never mind—for now.

Chief Freeman has decided not to call it quits in March. The chief, who has served two decades in the department’s top position, says he started getting worried on Friday about the timing of his exit. That’s when he says he received “some significant news” that property tax revenues for his department would be $16 million less than predicted—a foreboding figure since that pot of money funds about 70 percent of the agency’s operations.

“For any new fire chief, from inside or outside the department, that is a huge, ugly responsibility to have to face as a first step,” says Freeman, 64.

“Fortunately—and unfortunately—I’ve been through this before.

“After 21 years, I want to leave on as positive a note, and with as a good a feeling, as I can conjure up. I was right there until this [financial news] came along. I’d like to row a few more yards with things. It’s not like I feel I’m the only person who can do it. We’re just heading for some rough seas.”

Freeman compared his decision and the department’s money woes to the strategy of fighting a house fire. First, he says, you extinguish the immediate blaze in the room and then you check to see whether flames moved into the walls and attic.

“I thought I had the thing knocked down,” he says. “But I didn’t.”

A bit of good news for 2010 property taxes

December 1, 2009

Most Los Angeles homeowners will see a small drop, rather than a hike, in next year’s property tax bills, thanks to an unprecedented drop in the “inflation factor” that county officials use to assess property values. The drop, which will save the owner of a $250,000 home about $62, will affect about 80 percent of Los Angeles property owners, according to Los Angeles County Assessor Rick Auerbach.

The savings “affects both residential and commercial property owners,” Auerbach points out.

The reduced tax comes thanks to an arcane formula built into Proposition 13, the property tax limitation measure voters approved in 1978. Under Prop.13, taxes can rise up to two percent in years when the federal Consumer Price Index jumps two percent or more. Unfortunately, it almost always does.

Not this year. Recently, the CPI actually dropped, and the “inflation factor” the state uses to help the assessor’s office determine real estate value flipped to become a “deflation factor.” So instead of seeing an expected jump next year of $55, the owners of that hypothetical $250,000 home will see an actual drop of $7 from what they paid this year. That makes a swing of $62. “It’s not just the decrease that helps,” says Auerbach, “it’s the lack of an increase.”

About 350,000 of L.A.’s 1.7 million homeowners won’t get the reduction. That’s because they already had their property tax bills reduced when the  Assessor’s Office proactively recalculated the value of homes earlier this year in neighborhoods hard hit by the mortgage crisis.

Assessor’s Office proactively recalculated the value of homes earlier this year in neighborhoods hard hit by the mortgage crisis.

Here’s the bad news: the small savings won’t show up until the fall of 2010. The 2009 bill that Los Angeles County residents received this fall showed the usual increase. This year’s calculation was made in 2008—before the economy had headed so far south.

And, while we’re talking that 2009 bill, if you haven’t paid already, don’t forget to send your first payment to the Treasurer Tax Collector to beat the December 10 final deadline.

After all, who wants to spend next year’s tax savings by forking over late penalties now?

Santa Monica Mountains: An island of nature

December 1, 2009

Something remarkable is unfolding in the mountains above our urban sprawl—something for the ages. Parcel by parcel, acre by acre, we have amassed the largest swath of protected open space of any major metropolis in the nation. It’s a text-book example of collaboration between federal, state and local officials who worked hand-in-hand with grass roots groups dedicated to protecting the area from the kind of development that overtook the Hollywood Hills. For Zev Yaroslavsky, the preservation of the Santa Monica Mountains is both political and personal.

Video by John Vande Wege

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information