Disaster Readiness and Relief

Public health’s master of disaster

March 20, 2014

When Monday’s 4.4 earthquake struck Los Angeles, Stella Fogleman reacted like many parents—quickly stretching her arms over her two young children who had crawled into bed with her.

“I was like mama chicken with my wings,” Fogleman laughs.

Those wings stretch further than most. The 37-year-old was recently promoted to the position of interim director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health’s Emergency Preparedness and Response program.

She says that Monday’s 6:25 a.m. temblor—which shook people awake but didn’t cause serious damage—was a nice boost to her mission of getting people ready for a more serious disaster. Fogleman says her instinct to protect herself and those in her immediate area was the right one.

“It’s like the oxygen mask falling on an airplane,” she says. “You have to help yourself first, that way you will be able to help your community.”

Caring for communities has long been part of Fogleman’s job description. She got her start with the department in 2001 as a public health nurse, armed with master’s degrees in public health and nursing. Most of her time was spent monitoring tuberculosis cases to enforce strict protocols aimed at preventing the spread of the disease. From there, she moved to “toxics epidemiology,” shifting focus to diseases that result from toxic exposure.

Most recently, Fogleman led the development and implementation of the Community Disaster Resilience project—an alliance between the department, individual communities and emergency response agencies. The program uses public health department facilitators to educate community organizers on how to effectively prepare, respond and share knowledge. Fogleman hopes to keep that ball rolling in her new role.

“The key is collaboration,” she says. “You’re never as good by yourself as you are with others. Together, you have a broader set of resources.”

With only a few rumbles since the Northridge quake 20 years ago, Fogleman says it’s human nature to become complacent. But lack of preparation threatens to leave the region flat-footed when the next disaster strikes. According to public health studies, less than 20% of L.A. County households currently have earthquake kits. (The department’s website has a comprehensive checklist of what to include when creating your kit.)

But if fully stocking up seems a bit intimidating, Fogleman says a good first step would be to talk to neighbors about disaster strategies. Then, she says, you can begin to prepare and plan together.

It’s also important to secure homes by tethering tall furniture and securing books and glasses that could fly from shelves and cupboards, Fogleman says. People should know how to shut off gas and water in case of leaks, and families should go room-to-room to identify “safe places” to duck, cover and hang on—away from windows and under the cover of a sturdy table or desk, if possible. “That way you will subconsciously go to that spot,” Fogleman said.

Having the right supplies on hand can be a crucial. In the case of a widespread disaster, infrastructure may be damaged, cutting people off from the rest of the world. When an emergency response is spread over a large area, help might not come for days or even as long as two weeks, Fogleman says. Knowing first aid and CPR can help save lives if anyone is seriously injured.

As time goes on, people usually want to communicate with friends and family who live elsewhere. Having multiple ways of doing that—cell phones, internet and land lines—improves your chances of being heard. Fogleman says people can visit the Red Cross’s website to list themselves as “Safe and Well” so out-of-towners know they’re okay.

For those who want to go the extra mile, Fogleman recommends bereadyla.org, which has tools for preparing and community organizing. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department provides Community Emergency Response Team training on how to respond to all kinds of disasters.

In the event of a damaging earthquake, the Department of Public Health would work in the background while first responders tackle the situation in the streets, Fogleman says. It’s her department’s responsibility to minimize a disaster’s impact over time, addressing such things as food-borne illnesses and checking buildings for safety. “If we’re doing our job well, no one hears about us,” she says.

However, that’s something she hopes to change by highlighting the positive things the department does to help people during an emergency. She wants to improve her program’s outreach by increasing the number of its publications and creating a newsletter. Getting the word out is one of the cheapest—and most effective—ways of preparing people for the worst, Fogleman says.

Despite the serious nature of her job, Fogleman approaches things with a positive attitude that comes, she says, from a genuine love of public service.

“There’s no question that what I do every day helps people,” she says. “There’s a real satisfaction with that.”

Posted 3/20/14

Maximizing our “big gulp”

March 6, 2014

Here’s a factoid for those who think last week’s storms are water under the bridge now: Thanks to Los Angeles County’s flood control system, about $18 million worth of that rain is in the bank.

Los Angeles County Public Works Director Gail Farber reported this week that the county’s flood control infrastructure—sprawling, complex and generally taken for granted by Southern Californians—managed to collect and store some 18,000 acre-feet of rainfall by the time the skies cleared.

That’s enough water to supply 144,000 people for a year—roughly the population of Pasadena. Or, for Westsiders, a year’s worth of hydration for everyone in Santa Monica, the Pacific Palisades, Topanga Canyon and Malibu combined.

At about $1,000 per acre-foot for imported water, that’s good news, Farber told the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday. But in the midst of this drought, even more of that precious precipitation could have been saved had county dams not been clogged with dirt, sand and gravel from prior storms.

Instead, Farber said, water at Santa Anita Dam and Devil’s Gate Dam was released to maintain a safe capacity and prevent flooding.

“Had we more capacity behind our dams,” says Farber, “we could have captured more rain than we did.”

The storms dumped nearly a foot of rain last week on parts of Los Angeles County, raising water levels by as much as 36 feet at some of the county’s 14 dams. Though eagerly anticipated in this water-starved year, the rain also brought the threat of mudslides in foothill neighborhoods where brushfires have hit hard in recent months.

County workers had been out in force, working with surrounding municipalities and first responders to buttress vulnerable streets and help homeowners get ready, and were on hand round-the-clock as the storms hit.

Farber said the Department of Public Works alone “had more than 325 employees out there day and night, working 12-hour shifts in the pitch black with mud and debris flowing, and the rain coming down, and snow in the mountains, and hail sometimes.”

For all of that, the downpours scarcely made a dent in the three-year drought that has been withering the region, says Deputy DPW Director Massood Eftekhari.

“We’ve only accumulated 22 percent of what we normally accumulate, compared to prior years,” Eftekhari says. “We still have to conserve and collaborate to capture and utilize every drop we get.”

To that end, Public Works officials have been focused on maximizing the system’s capacity to better store rainwater when future storms hit. The county’s dams are set up not just to prevent rains from inundating neighborhoods in the flats and foothills, but also to collect storm water. That water later is released gradually onto massive spreading grounds where it percolates into the underground aquifers that supply about a third of L.A. County’s drinking water.

But each accumulation of rain also brings an accumulation of sediment and runoff. That sediment—hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of gunk in a typical year, enough to fill the Rose Bowl several times over—settles in dams and debris basins, and takes up space that otherwise would hold valuable rainfall.

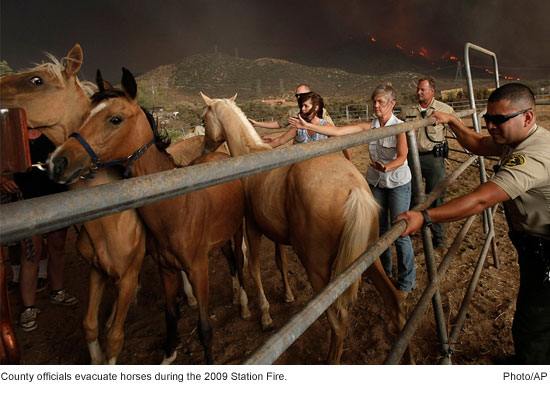

Typically, that gunk gets trucked out over time by Public Works crews who dispose of it in designated “placement sites”, landfills and rock quarries—an epic task that, until recently, followed a time-honored schedule. After the historic 2009 Station Fire, however, so many tons of charred debris washed into the system that the county’s entire sediment management plan had to be recalculated, says Farber.

Now, she says, at least four county dams—Devil’s Gate, Big Tujunga, Pacoima and Cogswell—have been put on an accelerated sediment removal schedule. Devil’s Gate, which is near Pasadena, is first in line, with an environmental impact report already underway, and Pacoima will be soon to follow.

That intensified need to make room in the system has drawn some fire from neighborhoods near some of the dam sites. Though they have the most to lose should the clogged dams overflow, they also stand to suffer the greatest inconvenience from the truck traffic inherent in removing millions of cubic yards of muck.

As communities around the dams measure their risk against the potential for upheaval, the officials noted that the county will be working with state and federal agencies to come up with efficient ways to capture more storm water and prepare for future storms.

Meanwhile, they remind, this is no time to let our guard down.

“This was a good-sized gulp, but the drought still is not over,” Eftekhari says.

Posted 3/6/14

Raising the alarm on fire perils

June 25, 2013

Record levels of parched vegetation, along with a long-running drought and predictions of hot, dry weather ahead have prompted fire officials to issue an unusually sharp warning about this year’s fire season:

It’s on a fast and furious pace—and may hold dangers unlike anything we’ve seen before.

Los Angeles County Fire Chief Daryl Osby, appearing with other fire officials this week, said indications add up to “probably the most volatile fire season that’s projected based on our 100-year history.”

Osby said in an interview that recent fires in Ventura County and in northern Los Angeles County have already provided a dramatic wakeup call that is mirrored statewide, where 500 early season fires have taken place so far this year.

Because the county hasn’t experienced a wildland fire on the massive scale of the Station Fire since 2009, Osby said, there’s plenty of highly flammable dead brush out there—in some areas, 100 years’ worth. What’s more, with rainfall totals running well below normal, measurements by the county fire department’s Forestry Division show that the amount of moisture in live brush has already fallen to critically dry levels, months ahead of schedule.

The Santa Clarita area hit the critical threshold of 60% “live fuel moisture” in May—meaning that the brush is so dry it will burn, in effect, like a dead plant. The rest of the county is expected to cross that dangerous threshold by the first of July, a good two months ahead of schedule.

“Sixty percent in the middle of May—that’s unheard of,” said Frank Vidales, acting chief of the Forestry Division.

Those conditions, coming in the midst of a three-year drought, are disrupting traditional fire patterns and throwing a curve to even the most experienced firefighters.

When some of them reported back from the frontlines of the Powerhouse Fire in the Angeles National Forest, which charred more than 30,000 acres, they told Osby:

“I’ve never seen that kind of fire behavior in my career. It sounded like not one, but two locomotives coming through.”

What was particularly worrisome about the blaze, Osby said, was that it was whipped up by ordinary winds off the ocean—not the fierce Santa Anas of autumn.

“That’s not typical. Typically at this time of year, we’ve still got a lot of moisture and a lot of green fuel out there,” Osby said. “That fire almost acted like the type of fire that we’d get in the fall—and that was just with normal winds off the ocean.”

To prepare for the challenges of such “extreme fire behavior” as the season progresses, county fire officials are preparing to fight back swiftly at the first sign of trouble.

“Regardless of the boundaries, we’ll try to get our resources there as quickly as we can to keep it from growing large. That’s our philosophy this year,” Osby said.

To that end, they’re moving up the schedule for bringing in the extra air power that traditionally comes into town during fire season. Super Scooper aircraft that usually arrive from Canada in mid-September are now projected to fly in around Sept. 1, and a heavy-lift helicopter is tentatively slated to report for duty on Aug. 1.

There’s also a rethinking of tactics underway.

“In some instances, based on projections and especially based on weather, it may be safer just to evacuate communities and come in afterward and try to save homes, rather than stay in there and try to defend it,” Osby said. “Because the last thing we want to do is put our firefighters in extreme danger, or our citizens.”

The heightened dangers of a volatile fire season also require more public vigilance. That means clearing brush around houses and other structures, getting familiar with the fire department’s Ready!Set!Go! program, and being aware that 94% of wildfires are set by people, sometimes intentionally but more often inadvertently with sparks from lawn mowers, weed whackers, power tools or even welding.

Finally, if a fire evacuation order is issued, residents should be ready to heed it—fast—regardless of whether they’ve toughed it out and stayed put through similar situations in years gone by.

“Psychologically, because they’ve experienced it in the past, they might say, ‘Well, we lived through this before; we can do it again.’ But it’s really important for our citizens to realize that this is not a typical fire season,” Osby said. “You’re not going to have your typical fire behavior. It’s going to be very volatile and when we ask them to evacuate, they need to evacuate early…Because your property can be replaced. Your life can’t.”

The Powerhouse Fire, above, is an early harbinger of the volatile fire season ahead. Photo/L.A. County Fire

Posted 6/20/13

From the ashes, monumental memories

November 20, 2012

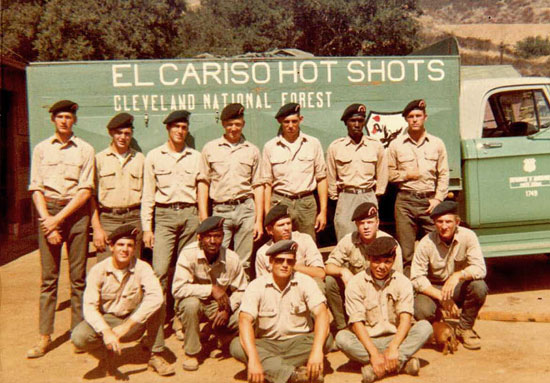

Rich Leak, in front with sunglasses, in the year of the Loop Fire. Five fellow "Hotshots" in this picture died.

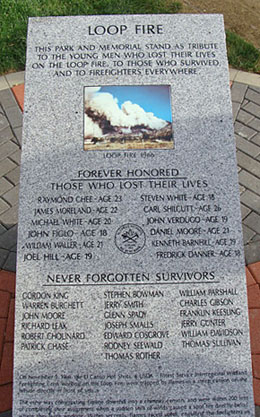

Last week, a memorial was relocated in the San Fernando Valley, a bit of granite that was moved for improvements at El Cariso Community Regional Park. The marker is modest, standing in sharp contrast to the tragedy it commemorates: Forty-six years ago this month, 31 young men were dispatched to a wildfire near Sylmar, and only 19 of them survived.

Rich Leak was 19 that summer, the gung-ho son of a Camp Pendleton fire captain. “All my life,” he recalls “I had wanted to be a fireman.” After attending a summer firefighting program at the U.S. Marine base, he had joined an elite ground crew of “hotshots” based near Lake Elsinore, so called because they were dispatched to the hottest parts of forest blazes. By 1966, his second year with the El Cariso Hotshots, he was a crew foreman, traveling the West to cut fire lines and clear brush around raging wildfires and “loving the excitement and the adrenalin rush.”

The Nov. 1, 1966, call came on a hot day at the end of a long fire season: A faulty power line had sparked a brushfire near Pacoima Dam. Whipped by Santa Ana winds, the blaze had charred some 2,000 acres around Loop Canyon. But it appeared to be dying by the time Leak and his fellow hotshots got what they regarded as an easy assignment—to scrape a fire line along a ravine near the smoldering fire.

“There wasn’t a lot of brush, and the fire was starting to lay down, so the line we were cutting didn’t have to be that big,” Leak remembers. The young men worked without gloves, their hands thick and calloused, their shirtsleeves rolled up. Their orange fire shirts had been washed so many times that they had long since lost their fire retardant coating. No one carried a radio or stood lookout. No one bothered to haul in a portable fire shelter.

And no one understood the dangers of the terrain, Leak says. Now firefighters know that a steep crease in a slope can act as a draft for combustible gasses. But on that day, no one knew that the 31 guys in orange hardhats were entering a death trap. They were nearly done with their work when, at 3:35 p.m., the wind abruptly shifted. A spot fire ignited on the hillside below them. As Leak looked up, the air around him suddenly went wavy.

Down the line an order came: Get out—now! But within seconds, a mighty rush of super-hot gas swept up the 2,200-foot ravine and exploded.

“It was like when you pour lighter fluid on a charcoal barbeque and put a match to it,” Leak remembers. “There was this big wooooof! And then all I could see was just a wall of orange flame. I had to look straight up to see blue sky.”

Leak held his breath so his lungs wouldn’t sear in the 2,500-degree heat, falling to his knees as the shock wave hit him. “Guys were yelling and screaming and praying and calling for their mothers,” he remembers. “I was talking to my Savior, that’s for sure.”

The Loop Fire would change safety protocols for fighting fires in narrow canyons, encouraging lookouts and radios and the development of much-improved fire gear, but not before it claimed the lives of 12 hotshots, most in their late teens and early 20s. Ten more were critically burned and scarred for life by the disaster. The fireball lasted no longer than 60 seconds, but in that time Leak suffered full-circumference burns from his elbows to his wrists, and lost four of his fingers.

After the smoke cleared, he recalls, “I was in shock, running around from one guy to the next, trying to put out the fire with my bare hands. At one point, I looked down at my arms and saw skin hanging down. All I thought was, ‘Wow, I guess I got burned pretty good.’”

It took three years and more than 30 surgeries for doctors to repair Leak’s wounds, using skin grafts from his stomach to repair his damaged hands. He has had to relearn how to type and eat with utensils. He struggles to pick up coins and he has to use both hands to screw a hose onto a faucet. He has no fingerprints.

“For a long time, I was very self-conscious,” he remembers. He went back to school at Palomar College near his hometown of Vista, earning an associate degree in business, thinking he might become a CPA. Then he heard the Vista Fire Department was hiring dispatchers. “It’s hard to describe unless you’re a firefighter,” he says. “It never goes away for me.”

He spent 30 years with the Vista Fire Department, working his way up to fire investigator before retiring to Hesperia 12 years ago. He married a friend’s neighbor and helped raise her two children. “To her, it was what was in my heart that mattered,” he says. “She told me she didn’t even notice I was burned at first.”

Then in 1996, the U.S. Forest Service sent him a notification: A memorial commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Loop Fire was going to be installed in El Cariso Park. Not all the survivors could make it, but some did. Sadly, they recalled the fallen.

“I still remember ‘em,” Leak says. “Raymond Chee, my crew boss, a Navajo I think from New Mexico—very quiet guy, used a brush hook. He was the best hook I’ve ever seen. The White brothers, Michael and Stephen, 22 and 18. They were from San Diego. Their dad was a captain in the Navy. It was devastating for their family.

“John Figlo, he was 18, kind of a quiet guy. Strong. James Moreland. He was in his twenties. Frederick Danner, a tall guy and a really good worker. He died in the hospital. Kenneth Barnhill, nice guy. I knew his brother. Carl Shilcutt, he was 26, one of the older guys on the crew.” He continues down the list: Daniel Moore, Joel Hill, William Waller. John Verdugo, a 19-year-old kid whose body was the first one he saw when he opened his eyes.

Leak kept in touch with the other survivors. He and another ex-hotshot, Ed Cosgrove, began giving talks together to fire academy classes. There were reunions—that’s how he found out that the 1996 marker was in serious need of repair. A drunk driver had hit it and cracked the granite. Skateboarders had worn down the lettering; taggers had marred it with graffiti.

So Leak spearheaded a move for a new one, only to learn that it was going to be moved anyway to make way for park improvements. Last week, a new marker was re-dedicated near a park office building. “It’s near a walkway,” he says. “Granite, just like the original.”

“There are times when I think, ‘What if I’d perished?’” says Leak, now 65. “But you can’t let things haunt you. You have to get over your injuries and go for it. I’m thankful to be here, living my life.”

Posted 11/7/12

Paging all healthcare pros

August 9, 2012

If you’ve got the skills, L.A. County wants you to be part of The Surge.

A new advertising campaign is being launched to expand the ranks of the county’s network of volunteer healthcare professionals who help out when major disasters or public health emergencies strike.

“No matter what happens with a disaster, there are always issues with medical needs,” said Cathy Chidester, director of the county Emergency Medical Services Agency. “Right now our hospitals are really maxed out, so, in case of a large-scale disaster, you are going to need extra professionals to staff those needs.”

Electronic billboard space valued at up to $250,000 recently was donated to the Los Angeles County Disaster Healthcare Volunteers, a collaborative effort led by the county’s Emergency Medical Services Agency and Department of Public Health, by outdoor communications companies, through a partnership with the City of Los Angeles. The donation was approved by the county Board of Supervisors on Tuesday.

One of the new billboard ads will recruit for the L.A. County Surge Unit, the largest of four volunteer groups under the “Disaster Healthcare Volunteers” umbrella. Another will spread the word about the Medical Reserve Corps of Los Angeles—a volunteer unit associated with the Los Angeles Department of Public Health. A third ad will be reserved for recruiting when a major disaster already has occurred.

The county volunteer collaborative was founded after the 9/11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina increased awareness of a need for backup healthcare personnel. Volunteers pre-register as professionals by entering their information into a database managed by the State of California. Their licensure and place of practice are verified by the program, and they are then considered “hospital ready.”

The Surge Unit seeks a variety of healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, EMTs and lab technicians. The unit is not aimed at recruiting first responders; rather, it seeks people to serve during the days following a large-scale disaster, when they would be contacted and mobilized to increase the capacity of hospitals and clinics.

Licensed mental health professionals are also vital to the effort, said Sandra Shields, Senior Disaster Services Analyst for the unit.

“Following a disaster, we expect a surge in people coming to the hospital concerned that they may be ill or have an injury, but are not actually hurt,” said Shields. Mental health professionals “can help manage the psychological casualties of major disasters.”

For more information about the Surge Unit or to register to help, visit the website or call (818) 908-5150. The unit also offers training sessions several times per year. The sessions are voluntary, as are all other aspects of the program. The personal information of volunteers is secured and can only be accessed by official representatives of the group.

The Surge Unit currently boasts 3,027 volunteers. With the help of the billboards, the program hopes to reach 4,000 by the end of the year. If you think you may want to help out during a disaster, signing up in advance is critical.

“The hospitals and clinics cannot effectively utilize spontaneous volunteers,” Shields said. “We want to use their skills appropriately and that’s easier if they are pre-registered.”

Posted 8/9/12

Fighting fire with some super friends

September 25, 2011

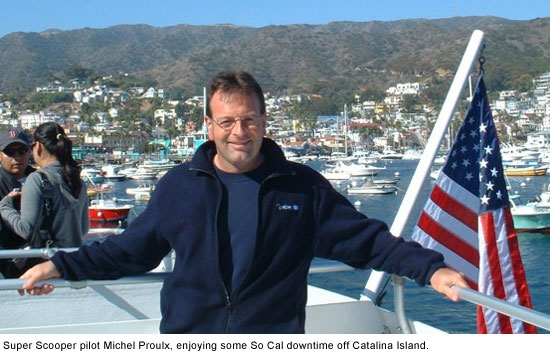

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

“It was OK,” he recalls with a laugh in his French-accented English. “You do not have snow in Los Angeles, but you have a lot of the winter decoration. One time in each four or five years, it is not so bad.”

For the past 18 years, an elite band of French-Canadian pilots and mechanics has left the Quebec backcountry to spend their autumns—and occasionally their winters—fighting fires in Los Angeles.

Fresh from their own wildfire season, they board two Bombardier CL-415 Super Scoopers leased from the government of Quebec by Los Angeles County. In the bright fixed-wing aircraft, which fly much lower and slower than commercial jet planes, they make the long trip south and west to the land of sunshine, celebrities and Santa Anas.

Once here, they check into the Burbank Holiday Inn—”our Hollywood house,” as Proulx jokingly calls it. Some meet wives and children. Some unpack sports equipment. Some pull out fiddles and guitars and hold Acadian jam sessions in their hotel rooms.

Then they get down to some of the most dangerous work on either side of the nation’s northern border.

“It’s really a unique situation, ” says Battalion Chief Anthony Marrone, who for the past seven years has acted as the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s liaison with the fliers from Canada’s Service Aérien Gouvernemental.

“They come here to risk their lives for people they don’t know, for a place that isn’t their country, for a job in which they’re not making a ton of money. But over the years, they’ve really become a part of our firefighting family.”

The famed Super Scoopers, which over the years have become a red-and-yellow icon of Southern California’s fire season, skim water from local lakes and the ocean and airdrop it onto wildfires. Los Angeles County has leased two of the sturdy aircraft during fire season annually since 1994, a year after the Old Topanga Fire killed three people and destroyed hundreds of homes in Topanga, Malibu and Calabasas. Each plane can pull in 1,620 gallons in 12 seconds, dump it and circle back at more than 170 miles an hour.

Marrone says the Super Scoopers cost the county about $2.75 million each fire season, which typically runs for 90 to 120 days, from September into December.

That price includes the pilots and their support crews, who work in 11-man rotations—four captains, four copilots and three mechanics. Each group stays for about a month, working out of the county’s air tanker base at the Van Nuys Airport, before a new group arrives via commercial airlines.

Over the years, the crews have been summoned to nearly every major fire in the county, particularly since the devastating 2009 Station Fire, when the U.S. Forest Service, which was managing the blaze, was criticized for not deploying more air power. The fire, the largest in county history, claimed the lives of two Los Angeles County firefighters while burning more than 160,000 acres and destroying some 200 homes and other buildings.

Since their arrival September 1, the planes and their crews have helped extinguish blazes in Newhall, Agua Dulce and Mandeville Canyon, among other hotspots.

“They’ve been there in Malibu, in the Buckweed Fire in Santa Clarita, in La Cañada Flintridge, in Diamond Bar and Palos Verdes, in Calabasas—everywhere,” says Marrone. “I was the helicopter coordinator on the Marek Fire in 2008 and they were out there long after any other air tanker would have had to turn back.”

The pilots downplay the danger.

“Sometimes we get bounced around when the Santa Ana winds pick up and we’re in the canyons, but mostly it is business as usual,” says Proulx, 46, who has been coming to L.A. since 2001. “We fly an aircraft that performs well in that kind of situation. When you’re using the right tool, it’s like driving a rig—it’s just a job.”

“We manage the risk carefully,” agrees chief pilot Villeneuve, who spent 11 years as a Canadian bush pilot before signing on with the Service Aérien Gouvernemental 15 years ago.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

In Canada, Proulx says, their work mostly involves dipping into remote lakes to put out forest fires. But L.A. “looks like Legoland from the sky—I don’t know the English word for it, but the city goes on and on forever and ever. When we drop the water, we’re about 75 to 100 feet above the ground and we can see the people waving and all that. Sometimes we can see the firefighters’ faces down there.”

In fact, Monette says, one of his most vivid experiences here was in 1999 during his first L.A. fire season, when he looked down from the cockpit and realized for the first time just how high the human stakes would be on this job.

“The fires were so close to the people and the cities—it made me feel that to miss just one drop would be awful,” remembers the veteran pilot. Now 46 and the father of two teenagers in Quebec City, Monette has volunteered for the Los Angeles County contract at least a dozen times since that initial flight.

For the Canadians, the L.A. rotation is more than just a chance to hone their job skills. It’s also an opportunity to create a traveling hybrid of north-south culture. Some, like avionics technician Jean Larocque, go mountain climbing in their off hours. Eric Tremblay, 45 and on his first stint here, went to Lake Arrowhead during some time off last weekend. Jean-David St.-Laurent, a 37-year-old serving his second year in L.A., says he has taken to starting each day with a brisk 2-hour hike through the chaparral in Wildwood Canyon Park, near the hotel.

Monette is drawn to the beaches when he manages to get a day off; over the years, he says, he has acquired two surfboards. He also has worked on his communication skills. “I was surprised when I came here that everything was more or less in Spanish, not English, so I learned the language,” he recalls.

Coming to California, he says, “was a dream, since I was a little boy—this place is so associated with freedom, the California way of life.” The reality is, of course, more complex, he has since decided. “How free are you, really,” he asks, “when your way of living turns out to be an eternal rush hour?”

Proulx, whose rotation starts in October, plans to find an amateur hockey game as soon as he gets here, a habit he developed after he hooked up with an organization for Quebec expatriates online. “This year, I’m thinking about Burbank—I’ve already played in Simi Valley and Van Nuys.”

And, he adds, he’ll be bringing his fiddle.

“Another guy brings his guitar, and sometimes in the evenings, we have a few beers and play music until the bursar from the hotel comes and tells us to lower the noise.

“We play funny songs, dirty songs…My favorite one is called in English, ‘You’ve Broken the Chain on my Tractor.’ Hey, you got to do something besides just wait for fires.”

But the best part of coming to L.A., they say, is the chance to be of assistance.

Each year, they are touched by the grateful fan mail they receive. Once, they were feted by Topanga homeowners; another time, a classroom of schoolchildren drew them a packet of pictures.

And the Canadians have a secret: L.A. brushfires die more readily than Quebec’s tree-fueled conflagrations, especially with fire operations as well-run as those here.

“In Canada, we can be working on a fire for days and days and you can almost never see the end of it,” Proulx says. “But in L.A., you take off and see that big smoke, and every time, we know we’re going to go work hard and fight hard, but we got a good chance to win.”

Posted 9/14/11

Teaming up for all breeds of disaster

September 21, 2011

People aren’t the only creatures who need help in a natural disaster—just ask the buffalo who was rescued from its backyard during the 2009 Station Fire. Or the zoo animals evacuated in 2007 when Griffith Park burned. Or any number of feline or canine survivors of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

People aren’t the only creatures who need help in a natural disaster—just ask the buffalo who was rescued from its backyard during the 2009 Station Fire. Or the zoo animals evacuated in 2007 when Griffith Park burned. Or any number of feline or canine survivors of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

For years, when Los Angeles County has needed help rescuing animals in peril, local municipalities and nonprofit animal welfare societies have willingly pitched in. The system has had just one problem, says county Directorof Animal Care and Control Marcia Mayeda: It hasn’t been official.

Now that situation is about to change, thanks to a mutual assistance agreement that spells out the framework under which the county and animal welfare groups will cooperate.

“No one has ever had a problem,” says Mayeda, “but over time, we began to realize that signing a formal Memorandum of Understanding might be good.” Although local agencies always responded gladly, she says, disasters elsewhere made it clear that potential liability questions and lines of communication could be clarified and federal reimbursement could be streamlined if a formal agreement were put in place.

This week, to the relief of Southern Californians of many species, the Board of Supervisors set the process in motion, approving an MOU with the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Los Angeles.

Mayeda says the agreement, which lays out general lines of authority and resource sharing between the county and spcaLA, will help local officials respond to disasters more efficiently. Over time, she says, the department will ask other animal services agencies to sign on; the MOU can be expanded to include various humane societies and local animal control offices as co-signatories in times of need.

“There are about a dozen agencies like this that we’ve worked with in L.A.County,” she says. Cooperation is crucial, she says, because “a disaster or emergency knows no boundaries.”

“There aren’t a lot of us in the world who spend our time being concerned about the welfare of animals,” says Madeline Bernstein, executive director of spcaLA. “So we can get a lot more done when we help each other out in mutual aid.”

Bernstein says spcaLA has teamed up with the county informally on many occasions, manning shelters when county workers were out doing rescues, rounding up and dispersing food at pet evacuation centers, even joining forces with county investigators to help prosecute cases of animal cruelty.

During the Station Fire, she says, spcaLA helped the county feed and house countless animals who were rendered homeless by the conflagration near the Angeles National Forest.

“We had dogs, cats, birds, a very large pig, a llama they were trying to pull to safety,” she remembered. “A buffalo who was someone’s pet. We evacuated part of the Wildlife Way Station in conjunction with the county. In a disaster, there are all sorts of animals other than the ones you’d expect.”

Bernstein says Hurricane Katrina and other recent natural disasters spurred the move toward formalization.

“After Katrina, when we could see that people were choosing not to evacuate rather than to leave pets behind, it became clearer that a disaster plan should include animals,” she says.

“We have done exactly this forever,” says Bernstein. “This just puts forth a more organized face.”

Posted 9/21/11

Reflections from 9/11’s front lines

September 8, 2011

In the nightmarish days after the attacks of September 11, 2001, with fears running high of another strike on the way, L.A. County Fire Department’s elite urban search and rescue team remained in place—first in line to respond here if the West Coast was next.

But some of its members, called up by FEMA and working on their own time, traveled east to lend a hand at the World Trade Center and Pentagon sites. In the 10 years since, their experiences in those dark days and nights have stayed with them and, in some ways, shape their world view today.

Captain Dave Norman, chosen to help oversee night rescue operations at the World Trade Center site, traveled to New York three days after the attacks. “It was complete chaos: thousands of people, bucket brigades, crane operations going on, a mass of humanity throughout this 16-acre collapse site,” he recalled.

His first night on the job—one of 18 he spent at the site—Norman saw one of the rescuers emerging from the rubble with a New York fire department helmet in his hand.

“Coming out of the void, all he had in his hand was that helmet with a No. 1 on it. A very powerful moment, if you will.”

Norman, who works on one of the county’s two Urban Search and Rescue teams,Task Force 103 based in Pico Rivera, said it is hard to convey the full force of what went on in New York. “You really can’t explain it,” he said.

But he knows his 9/11 experiences, along with his wife’s recent bout with cancer, have changed how he looks at things.

“It’s a reminder of how lucky we are to be alive, contributing and having a purpose, not only in your professional life but in your personal life and your relationships. Are you contributing enough? Being the best person you can be? These were just ordinary people, heading to work. Just like that, the world changed.”

One of Norman’s colleagues, Battalion Chief Larry Collins, also got the call to head east after the attacks. He recently reflected on it all in an article he wrote for the firefighter publication “Straight Streams.”

“Those of us who responded from the West Coast saw first-hand what a catastrophic terrorist attack looks like, and we’re forever reminded that it can happen again anywhere in our nation,” he wrote.

For Collins, the losses that day were as much personal as professional: Ray Downey, the New York fire department deputy chief with whom he’d long taught rescue operations classes, was among the hundreds of FDNY firefighters killed that day in the towers.

Had New York been spared, Downey almost certainly would have reported to the Pentagon, helping to lead the search and rescue response there. As it was, that role fell to a national cadre of experts, including Collins, who remembers saying goodbye to his New York colleague in July, 2001, after a class they’d taught in Baltimore, with their profession’s trademark sign-off, “See you on the big one.”

They jokingly agreed that was likelier to be in L.A. than New York. “It turned out both of us were wrong,” Collins wrote, “because three months later L.A. County and L.A. City firefighters were in New York digging for survivors in the wreckage of the World Trade Center.”

Collins, whose recent deployments include the earthquake and tsunami in Japan and Hurricane Irene on the East Coast, was a captain when he headed to the Pentagon shortly after the attacks, helping to supervise night operations at the site. Since promoted to battalion chief, he now oversees stations in the unincorporated areas of Florence-Firestone, Willowbrook, and the cities of Huntington Park, Lynwood, South Gate, and Cudahy, while also serving as a task force leader of the department’s urban search and rescue team.

The expertise garnered after 9/11 in Washington, D.C. and New York, and at disaster hot spots around the world, has made L.A. County a safer place—even though most folks on the street might not be aware of it, he said.

“Those people on the fire truck are often some of the most experienced rescuers in the world,” he said. When catastrophe strikes, “you want people who have seen maybe even bigger things than that, and have done it over and over again.”

And, as Collins prepared to head to New York for 9/11 observances this weekend, he made it clear that the search and rescue wisdom of Ray Downey and his New York team didn’t die with them in the towers that day. He said those FDNY colleagues were instrumental in helping L.A. County build its own urban search and rescue team—a legacy of shared knowledge, and of pulling together in a crisis, that continues to this day.

“They helped us immensely,” Collins said, “and that’s the power of sharing that goes on.”

Posted 9/8/11

Emergency prep takes a village, too

August 31, 2011

National Preparedness Month couldn’t come at a more appropriate moment. With the Northeast recovering from an atypical hurricane just one week after it was struck by a rare earthquake, the whole country is reminded just how tough disasters are to forecast. Preparation is vital, and Los Angeles County is getting in on the efforts.

National Preparedness Month couldn’t come at a more appropriate moment. With the Northeast recovering from an atypical hurricane just one week after it was struck by a rare earthquake, the whole country is reminded just how tough disasters are to forecast. Preparation is vital, and Los Angeles County is getting in on the efforts.

“One thing we can be sure of is that emergencies happen, disasters happen,” said director of L.A. County Department of Public Health Dr. Jonathan Fielding, speaking before the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday. “They’re not things we can project, but we have to be prepared.”

While most folks in L.A. County understand the importance of maintaining an emergency kit, Fielding points out an important aspect of preparedness some may not have considered–community cooperation.

“We have to start our preparation not just about ‘me,’ but about ‘we,’” he said.

“Connect, prepare and respond” has become the official catchphrase for an effective, community-based response. Neighborhoods “connect” by meeting to share contact info and resources. Together, they can then “prepare,” setting up methods of communication and creating a neighborhood map with evacuation routes. Finally, the community “responds” when a disaster happens. Emergency personnel are likely to have their hands full at such times, so cooperation is crucial to protecting all of us, especially vulnerable groups like the elderly and disabled.

The Department of Public Health’s website has preparedness tips, including ten things you should have in an emergency kit and how to create a family emergency plan. It also lists links to other important emergency resources. Residents can also call the Emergency Preparedness Hotline at 1-866-999-5228 and speak with operators in eight different languages.

National Preparedness Month is organized by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security with Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American Red Cross and others. These groups have valuable online resources available to the public, available here, here, and here. The Red Cross even has a user-friendly tool that goes step-by-step through emergency preparedness so there’s no excuse for getting caught unprepared when disaster hits.

Posted 8/31/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink