Jail phone calls ring up big bills

November 2, 2009

Responding to complaints about the high cost of telephone service in Los Angeles County jails, the Board of Supervisors has moved to open up bidding on the multi-million dollar jail phone contract in an effort to lower the cost of calls while still providing key funding for jail programs.

Responding to complaints about the high cost of telephone service in Los Angeles County jails, the Board of Supervisors has moved to open up bidding on the multi-million dollar jail phone contract in an effort to lower the cost of calls while still providing key funding for jail programs.

The jail phone contract with the Sheriff’s Department governs the rates charged when inmates call family, friends and attorneys from the jails’ nearly 4,100 telephones. The current provider is Global Tel*Link, a privately-held Alabama firm that operates phone services in jails and prison systems nationwide, including many in Southern California.

The contract brings in about $30 million a year. The company keeps 48 percent while paying 52 percent to the Sheriff’s Department, which uses the money to help pay for inmate programs and jail maintenance.

The contract, which runs through December 2010, allows GTL to charge $3.54 for the first minute of a collect local call from the jail, making the average call of 17 minutes a $5.20 expense for the inmate families, according to a 2008 report by the county CEO’s office, prepared for the Board of Supervisors. The county initially cut the deal in 2005 with the then-SBC/AT&T, which later sold its jail business to GTL. Inmates can also buy prepaid phone cards and save 10 percent on calls, but few do.

The rates are among the highest in the region, about 10 to 30 percent above most prices paid in other county jails and many prisons nationally.

GTL says the county negotiated and approved the contract in 2005. The company says comparisons of per-call rates from one jurisdiction to another are unfair. “Variability in rate structures and costs [between counties] is to be expected” because each jail system negotiates prices based on a different menu of services and product features, GTL’s western regional vice president for sales, Michael Palovik, said in an e-mail exchange.

Palovik says GTL prices in L.A. can be as low as $3.35 for the first minute during daytime local collect calls; later minutes can cost as little as $.759 per minute.

The amount of money charged is controversial because studies show that maintaining strong family contact during incarceration through phone calls, correspondence and visits can aid parole success and reduce recidivism.

The supervisors believe it’s possible to get a better deal for both the inmates and the county if several companies vie for the next contract, which begins in January 2011. “The one way you find out about the best deal is you put all the sharks in one tank and let them fight it out,” Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said during a board meeting last year.

County CEO William T Fujioka agreed. “I’m absolutely convinced, you put this out on the street, we’re going to get a more competitive contract,” he told Supervisors during the 2008 meeting. “The County wants to achieve two goals. One goal is to lower the rates. The second goal is to make sure that this valuable resource for the Sheriff’s Department is maintained.”

Supervisors rejected a GTL offer to pay the county a $3.5 million fee to extend the current contract through 2013. The supervisors’ goal in putting up the contract for bid is to lower per-call costs to families while maintaining steady revenues for the Sheriff’s Department.

The fund nets about $15 million a year for the sheriff’s Inmate Welfare Fund, which helps supplement the costs of inmate education, drug recovery and training program as well as maintenance programs in the overcrowded jails.

The Sheriff Department’s 52 percent cut is “at the high end of the range” compared to figures paid to other correctional facilities, according to a County CEO’s report last year. Most commission rates, as they are called, fell between 40 and 56 percent.

As his office is preparing the terms of the Request for Proposal, the initial step in soliciting new bids, Sheriff Lee Baca is pushing against any plan that would lower revenues to the department. “I oppose any effort by the Board to alter the rates through a bid process,” Baca told Supervisors in a letter dated September 22.

“We can’t look at this from the perspective that the inmates are overcharged, because they are not,” he told Supervisors at a hearing last year.

The first-minute charge exceeds every Southern California county except Orange County, which charges a flat $4 rate whether the call lasts a minute or an hour. The price of the average Los Angeles call, at $5.20, is roughly 10 to 30 percent higher than other jurisdictions, except San Bernardino ($6.40)—including several operated by GTL. A 17-minute call from an LAPD lockup is $4.48, similar to Ventura County’s $4.49. In Riverside County, the call would run $3.73.

“How could it be possible that a company can charge people fees like that?” complains Evelyn Boligan, whose son Nicholas, 21, awaits trial for attempted murder. Boligan, a Department of Motor Vehicles employee from Gardena, paid over $900 in collect phone calls during her son’s first five months of incarceration in 2007 at Men’s Central Jail.

She complained to the company without success about charges for dropped calls or conversations she had to cut short because of static or overwhelming background noise at the jail. But she is unapologetic about the value of staying in touch with her son. “I had to pay those bills,” she says. “When it’s your child, you want to know that he’s okay.”

GTL’s Palovik counters by pointing out the rates are set in the terms of the county contract. The decision as to how often and low long to talk with inmates is at “the discretion of persons who chose to accept those calls,” he says.

Some families say they have had to reduce phone calls from the jail. After Janet Harris’ son Andrew Arthur, 20, was arrested on assault with a deadly weapon charges this summer, she says her phone bill shot up significantly. Even the second month’s additional $68 in jail calls was too high for Harris, a custodian at LA County + USC Hospital. “I had to tell him he could only call me every two weeks,” says Harris. “It was too high.”

Defense lawyers complain that the collect call system interferes with client contact. Glendale criminal attorney Sue Brown says she cut off client calls from jail clients after getting angry over high rates and charges for calls she never received. “It’s really a rip-off,” Brown insists. “Now I go visit my clients at the jail. It really interferes with my representation, but I don’t think I have to sacrifice my principles to represent my client.”

Attorney Christopher McCann notes that whenever he adds another $50 to the debit account that allows the clients to call him collect, GTL takes a $9 cut. “They call it a one time transaction fee,” he complains. “Well, it’s one-time every time I do it.”

H1N1 vs. “The Invincibles”

November 2, 2009

It’s safe to say that thermometers are not a typical part of dorm welcome kits for incoming UCLA students.

It’s safe to say that thermometers are not a typical part of dorm welcome kits for incoming UCLA students.

But they are this year. It’s just one way that H1N1, known on the street as the swine flu, is changing the flu season conversation for a whole generation of young adults not used to being in the “high priority” hotseat.

In short: This ain’t your grandma’s flu.

Emily Bossak, a 22-year-old UNLV graduate who recently moved here and plans to attend UCLA law school, wouldn’t ordinarily get a flu shot but decided to get vaccinated recently at Los Angeles County’s first H1N1 immunization clinic in Encino.

“Usually when I think seasonal flu, I think people 50 and over,” Bossak says.

Senior citizens, who ordinarily turn out in the biggest numbers for seasonal flu shots, don’t even make the priority list for H1N1—unless they fall into one of the other risk groups. (In addition to young people from ages 6 months to 24 years, those groups are: pregnant women; those caring for infants younger than 6 months; health care and emergency workers, and people from ages 24 to 64 years with health conditions that put them at higher risk for flu-related complications.)

Medical officials believe that older people may have picked up some immunity from exposure to a similar flu strain in the 1950s. In any case, those most likely to be hospitalized this time around are in their teens.

“I actually read that book ‘The Great Influenza,’” Bossak says, noting that she was struck by the magnitude of the 1918 pandemic—“especially with all the deaths in my age group.” She adds that her father, a doctor, recently told her that one of his colleague’s daughters had died of the disease.

Does this kind of heightened awareness mean that all her friends are lining up to get vaccinated, too? Not so much. “They’re more afraid of the symptoms of the shot,” Bossak says.

To encourage awareness, dispel myths, promote good flu season hygiene and put out fast-breaking news about H1N1—particularly about nationwide vaccine shortages—Los Angeles County public health officials are using youth-friendly channels such as Twitter and YouTube to spread the word, along with the department’s website.

In addition, Dr. Alonzo Plough, the department’s director of emergency preparedness, recently provided a briefing for college newspapers.

Young adults—sometimes described as “the invincibles” for their it-can’t-happen-to-me outlook—are an important group to reach, health officials say. “That’s the age where we all believe we’re invulnerable,” Plough says. Not only do they often live with roommates—“How quickly this can spread in a dormitory population!”—but this age group also has a “tendency to be uninsured.”

For people who cannot get immunized through a private provider (or in the case of students, through a university health service), the county is hosting a series of free H1N1 vaccination clinics, at locations including Hollywood Park and the Pomona Fairplex, as well as at recreation centers and a number of college campuses, including two at the USC-Lyons Center and Santa Monica College. (The complete list is here.) Because of vaccine shortages, however, officials for now are asking those who do not fall into priority groups to wait until expected shipments arrive in coming weeks.

At the county’s first vaccine clinic in Encino, Dr. Jonathan Fielding, the county’s director of public health, received the first shot. Part of the healthcare worker priority group, he suited up in his white doctor’s coat and administered the vaccine to Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. His priority group: adults with underlying medical conditions, in his case, diabetes.

“When was the last time you gave a shot?” Yaroslavsky joshed as he rolled up his sleeve, smiling and later telling reporters, “Jonathan Fielding actually administered the shot and I didn’t even cry. It was a wonderful experience.”

After that came Jaxon Irribarra, 13 months, and his 24-year-old mother, Jessica Gonzalez.

“This is the first time I’ve gotten one,” Gonzalez says. “We both fall in the high risk groups, and I thought it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

Yaroslavsky calls the rollout “the largest mobilization of public health since the polio epidemic of the mid-1950s” and called on the public, particularly those in priority groups, to get their shots, too:

“By receiving the H1N1 vaccine, you not only protect yourself, but you protect your loved ones as well. You also protect your co-workers, students, children in schools as well as the rest of the community.”

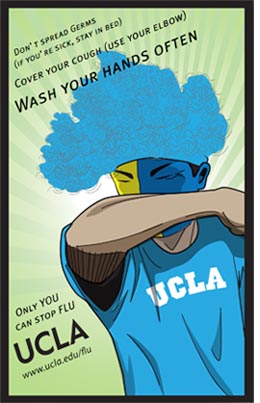

Looking out for oneself—and for others—has been a big part of the message at UCLA, where university officials have created a self-screening questionnaire for students, developed a Create Your Flu Pack guide (“Be a Bruin Flu Fighter!”) and are offering an online “H1N1 Influenza Vaccine Wait List” to help organize administering the still-scarce vaccine.

It’s a message that’s hard to miss on campus.

“There’s posters, there’s banners, there’s hand sanitizer dispensers,” says James Gibson, director of UCLA’s Department of Environment, Health & Safety. “At our (seasonal) flu clinics, we’ve vaccinated many more people than we have in the past. It’s a much bigger issue that it has been in the past.”

Some 1,200 students have come down with influenza-like illnesses over the past four weeks, according to Susan Quillan, chief of Clinical Services at UCLA’s Arthur Ashe Health and Wellness Center, but only 250 have gone to the Ashe Center for treatment.

That’s an indication that students are following advice to “self-isolate” when they come down with flu-like symptoms, and that roommates and friends are pitching in to care for those who fall ill.

“The majority of the people in the dorms are responding to the education,” Quillan says.

Andrew Hattala, 24, a resident assistant at UCLA’s Hedrick Hall, said the dorm had quarantining rooms available and noted that housekeeping was doing extra sanitizing when requested. And he noted that washing your hands and “coughing into your elbow” were suddenly statements of personal responsibility.

“You see how important the things are that you learned in elementary school.”

Innovative probation/police teams cut valley gang crime

November 2, 2009

The LAPD and the county’s Probation Department joined forces for the first time more than two years ago to battle the San Fernando Valley’s rising tide of gang violence. The idea: to embed a deputy probation officer in LAPD gang details in six Valley stations to provide a missing dimension to gang enforcement.

The LAPD and the county’s Probation Department joined forces for the first time more than two years ago to battle the San Fernando Valley’s rising tide of gang violence. The idea: to embed a deputy probation officer in LAPD gang details in six Valley stations to provide a missing dimension to gang enforcement.

The result, according to police and probation officials, has been a significant drop in gang-related violence in the Valley since the Community Impact Teams hit the streets. Valley gang crime has fallen 18 of the 28 months the program has been in existence – including ten of the latest 12 months, ending in June, 2009, for which statistics are available. “It’s clearly trended down and CIT has been a part of that,” says Paul Vinetz, Probation Director for the Third District, who helped design the program.

As members of Community Impact Teams, six deputy probation officers roll with LAPD Valley gang officers to answer emergency calls as well as make proactive community police stops. They focus on assessment and case management of high-risk gang-involved offenders in crowded neighborhoods. The probation officers have conducted thousands of face-to-face contacts, home visits and searches that have yielded hauls of firearms and other weapons. In 2009, CIT officers seized 35 firearms through August, including one June incident that yielded a sawed-off shotgun and two assault weapons.

Teaming up with Probation officers give LAPD gang cops a greater ability to identify probationers quickly and make warrantless “probation searches” of cars or homes that can turn up drugs or weapons. Being out with the LAPD officers gives the Probation Department greater street presence to spot problems with individual probationers. Working in dense neighborhoods with significant gang problems, probation officers say that their skills and sensitivity have helped them to flag hot spots and act on crime trends that might be invisible to traditional law enforcement alone. “We bring a different focus that complements what the LAPD officers do,” says Probation Director Jose Jimenez, who heads the Intensive Gang Supervision Program that includes the CIT.

Beyond crime suppression efforts, the embedded probation officers also provide another set of eyes and ears on the alert for youngsters at-risk from exposure to gangs and drugs. Probation officials say officers can then make more timely and effective referrals to the Department of Children and Family Services’ child abuse hotline. They can also refer probations and families to other services, including mental health, education, drug treatment and domestic violence.

Making a joyful noise

November 1, 2009

The fireworks cascading above the Hollywood Bowl have died down. So, for the moment, has the roar of Gustavo-mania that has greeted the arrival of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s charismatic new conductor, Gustavo Dudamel. But in a small practice room on the second floor of a building next to the 1932 Los Angeles Swim Stadium, something is burning bright.

It’s a weeknight, just before Halloween. Paloma Udovic, 28, is heading into her fourth straight hour of teaching here at the Expo Center near USC, where her organization, the Harmony Project, is part of a unique collaboration with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the city Department of Recreation and Parks. She’s upbeat and gently welcoming as the viola section files in: Cathy Gomez, Claudia Tinajero, and the Pinto-Quintanilla sisters, Amy, 10, and Arian, 13. The Pinto-Quintanillas are a force to be reckoned with around here—a third sister, 16-year-old Adria, also plays cello in the orchestra.

While the Pinto-Quintanilla family trifecta is notable (“I think that’s the record,” Udovic says), it’s hardly unusual.

There’s an infectious energy that seems to pull everybody—brothers, sisters, parents, grandparents, cousins—into the vortex of Youth Orchestra Los Angeles (YOLA), an ambitious and growing program modeled on Venezuela’s legendary El Sistema, whose most famous alum just happens to be that cool new guy on the podium at the Phil.

YOLA isn’t an orchestra per se. Gretchen Nielsen, the Phil’s director of educational initiatives, describes it as a movement to establish youth orchestras in under-served communities. “When you do something this intensively,” she says, “you’re building a sense of community, a sense of family. These kids don’t have easy lives. A lot of them are taking care of siblings, or come from broken homes…If they’re late for class, you ask what’s going on, but you don’t scold.”

It all started when a Los Angeles Philharmonic delegation visited Venezuela to observe El Sistema in 2007—back when the notion of landing Dudamel as the orchestra’s music director was still under wraps. “That trip kind of opened everyone’s eyes,” Nielsen says.

“What happened in Venezuela had to happen here.”

The YOLA EXPO Center Youth Orchestra program is the first such venture, but it won’t be the last. With 200 students ranging in age from seven-year-olds to teenagers now playing in two orchestras at Expo, the Phil is planning to add another site next year, on its way to yet another by 2013, serving a total of 1,000 students.

The YOLA EXPO Center Youth Orchestra program is the first such venture, but it won’t be the last. With 200 students ranging in age from seven-year-olds to teenagers now playing in two orchestras at Expo, the Phil is planning to add another site next year, on its way to yet another by 2013, serving a total of 1,000 students.

The Expo Center kids were a focal point of the huge free concert at the Hollywood Bowl that inaugurated the Dudamel Era in Los Angeles.

More than a month later, everybody who was there is still saying the words “October Third” like somebody might say “The Fourth of July”—a holiday, a triumph, a date that will live in ecstasy.

“I thought it was going to be a really big thing. It was even bigger than that, especially when Jack Black came on,” says 13-year-old Arian Pinto-Quintanilla, a student at Palms Middle School in West L.A. “We stayed for the fireworks. Everything was, like, movie-ish.”

As for Dudamel, “he treated us as if we were his actual orchestra.”

Which, in a sense, they now are.

At the rehearsal for the Hollywood Bowl concert, Dudamel, wearing jeans and a black T-shirt inscribed with “YOLA” and “Expo Center Youth Orchestra,” is a natural, encouraging and funny as he leads the students through an arrangement of Beethoven’s Ode To Joy.

He cracks them up. “Violins, I can see you play but it’s so boooooring.” He asks the cellists if they’re a bunch of 85-year-olds. He makes them sing. He precedes a downbeat by counting in Spanish: “Uno, dos, tres, y….”

He’s helping them see their youth as an outrageous power source, something that can help them play—and be—bigger. “What is the size of our instrument?” he asks the cello section. “Is it like this?” he says, indicating tiny. “Or like THIS?”—arms spread wide.

Ode to joy, indeed.

Star-studded concerts at the Hollywood Bowl are one thing. The hard slog of day-in, day-out practicing is another.

Expo Center orchestra students have three nights of group sectional lessons every week and a full orchestra rehearsal on Saturdays. Some, like the Pinto-Quintanilla girls, play in more than one orchestra.

But, amazingly to anyone who ever resisted piano lessons or been pushed into patent leather shoes and paraded into a symphony hall against their will, the YOLA/El Sistema method actually seems…fun.

“It’s very different from the teaching I’ve done where the parents are forcing them,” Udovic says. Here, at the Expo Center, “it’s the other way around.”

For the kids, part of the appeal has to be the pure play of it all. Before the viola sectional that the Pinto-Quintanillas take part in, the violins have their turn.

A little girl in a sparkling white-and-silver costume floats around the room playing “Invisible String Master,” poking backs, correcting wrist positions, delicately but insistently making her compatriots look more like, well, real violinists.

The informal mood continues into the viola sectional.

“Can we make sure our booties are scooted all the way to the front of the seat?” Udovic urges.

Udovic asks whether the scale they just played was in tune. One of the girls admits she wasn’t listening.

“Listen,” Udovic tells the girls, imparting life wisdom as well as musical advice. “It’s not just in music. It’s in lots of other things. It’s a good thing to do.”

“I view this as a social program, with music as the mode,” says Udovic, 28, a Northwestern grad and self-described “Suzuki baby” who picked up her first violin at age 3. She’s part of a cadre of more than a dozen “teaching artists” on the program staff, working musicians with a gift for instructing young people and an interest in social progress.

Mirna Quintanilla, a medical assistant in Beverly Hills, is the mother of Adria, Arian and Amy—her “three A’s,” she says. Those letters aren’t just initials: “That’s what I tell them for the grades. Only A’s.”

After getting divorced, Quintanilla says, “my priority was to keep them busy.” There were art classes and music, lots of it. They haven’t looked back. “We are busy seven days a week,” she says. Even though they log a lot of miles from their home near the Expo Center (the program aims to serve kids living within a 5-mile radius), you won’t hear her complaining.

“I don’t mind,” she says. “My priority now is my three daughters.”

At left, Amy Pinto-Quintanilla, 10, practices the viola. Her sister, 13-year-old Arian Pinto-Quintanilla, right, plays viola, too. Both also play the violin.

The Expo Center program is free, as are the instruments. “To pay for these classes, we could not afford it,” Quintanilla says. And the results: priceless—like having your daughters perform at the Bowl, under the direction of Dudamel. “I invited all my friends,” Quintanilla says. It wasn’t until the next day that the accomplishment actually sunk in for her daughters: “We played in the Hollywood Bowl.”

Beyond the thrill of such moments, the program derives much of its power from its commitment to spreading its mission and methods around the world.

Dudamel’s mentor, El Sistema founder Dr. José Antonio Abreu, won a 2009 TED award and is using the $100,000 prize to endow the Abreu Fellows Program at the New England Conservatory of Music. Abreu fellows will perform internships at El Sistema-inspired “nucleos” across the U.S.; some will be at Expo Center this spring.

Also in the works: a program developed with USC’s Musical Education Department to begin bringing early childhood music classes to the 3- to 5-year-olds in the Expo Center preschool starting in January.

The Colburn School, across from Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles, also is getting in on the act with the Colburn Mentorship Program, in which 20 conservatory students will be paired with 20 Expo Center students for one-on-one lessons.

Abreu, in town for the Dudamel debut concerts, recently dropped by the Los Angeles County Hall of Administration to pay a visit to County Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Gloria Molina, along with Philharmonic President and CEO Deborah Borda.

They talked about Abreu’s now-famous observation that children who hold hold instruments can’t hold guns, and recalled the advice he gave Borda when they talked about importing El Sistema to L.A. “Think big but start small.”

The advice now: “Grow without fear.”

Shout it from the mountaintop—it’s Ballard Mountain!

November 1, 2009

Unexpected coalitions can move a mountain. Sometimes they can even change the mountain’s name.

That much was abundantly clear on a recent sunny Sunday morning at First A.M.E. church in Los Angeles, when an array of people from far-flung corners of Los Angeles assembled to pay tribute to a man, a mountain and a shared purpose that, improbably, had brought them all together.

There was a history professor, a geophysicist, a retired entertainment executive, a Los Angeles County supervisor and a retired city firefighter with much of his extended family in tow.

And there was the leadership and congregation of First A.M.E.—there to celebrate the journey that recently culminated in a new name for a prominent Santa Monica Mountains peak: Ballard Mountain.

Until this fall, it was called “Negrohead Mountain”—a ‘60s-era modification of its earlier name, which contained a racist slur.

John Ballard

“Before it was Negrohead Mountain, it was another N-word Mountain,” Pastor John J. Hunter told the congregation, celebrating the fall of “another symbol of racism” and thanking Yaroslavsky for his leadership.

“Name the mountain for the man, not his race, and that’s what we’ve done,” Yaroslavsky said. “It’s the right thing to do and it’s a great thing to honor a man who’s been gone for almost 100 years.”

Kenneth W. Hudnut, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey, presented a map bearing the new name to Ballard’s great grandson, Reginald Ballard, Sr. The United States Board on Geographic Names made the change Sept. 9, at the request of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, which adopted Yaroslavsky’s proposal to do so.

Reginald Ballard, 84, retired from the Los Angeles City Fire Department as a captain in 1978. In the mid-1950s, he had been part of a group of firefighters who challenged the department’s segregation practices, eventually prevailing and opening up promotional opportunities and integrating firehouses.

Although Reginald Ballard had been a part of history in that case, he didn’t know much about his own—until recently.

He said his father, Dr. Claudius Ballard, had been a good doctor but not much of a communicator. “I didn’t know anything about my family tree,” Ballard said. “We didn’t sit around the table discussing things.”

But, after reading an extensive article in the Los Angeles Times (here) that detailed the work of Moorpark College history professor Patty Colman on the Ballard family saga—and the efforts of neighbors who started the push to change the mountain’s name—Ballard and his grown children realized they might be looking at a long-lost link in their family history.

They connected with Colman and with neighbors Paul Culberg and Nick Noxon. Eventually, the connection to John Ballard was confirmed through marriage and death records.

Culberg, a retired entertainment executive who lives near Ballard Mountain, helped get the name change underway by telling Yaroslavsky about it at a holiday party last year. Culberg said he and his wife, Leah, were thrilled to have been part of the coalition that made it happen—and delighted to have been invited to First A.M.E.

As for Colman, “the biggest thrill of all for me was when we actually met the descendants. Sitting there chatting with Reginald Ballard, that’s the closest I’ll get to John Ballard.”

In addition to The Times, the story has been chronicled on television and newspapers from the Agoura Hills Acorn to the New Zealand Herald.

Ryan Ballard, Reginald Ballard Sr.’s youngest child and the great-great-grandson of John Ballard, took a special joy in bringing his wife, Nicole, and their two young sons to the service.

“As a father, it’s quite significant,” said Ballard, 37, a special education teacher at Locke High School. “You’re always thinking of what you’re going to leave to your kids. Who’d have thought that this would be left for them as part of their legacy?”

The family hasn’t hiked up to the Ballard Mountain—yet.

“You know the plan is already underway,” Ryan Ballard said.

Phil’s new red ride

October 31, 2009

Angelenos complain about traffic like urbanites back east complain about the weather. But with apologies to Mark Twain, we’ve found at least one Los Angeles resident with a novel way to actually do something about it.

Phil Hess is a New York transplant who’s lived and worked in L.A. for nearly two decades. For years, the Hancock Park lawyer navigated the city streets as conventionally as the rest of us – comfortably gliding around town encased in his Lexus, but increasingly sweating traffic that seemed to grow exponentially worse by the day.

Today, however, Hess has largely ditched the cushy sedan for a flashier ride: a “Ferrari red” Vespa GTS-250 250-cc motor scooter. And the way he tells it, it was practically love at first sight.

A former planning deputy for retired County Supervisor Ed Edelman, Hess has since built up a thriving private practice as a land-use attorney with cases ranging from Thousand Oaks to the South Bay. “My two most common meetings are meetings with clients or court dates, and the Vespa is essential to be able to do either of those.”

What finally gave him the idea to jump out of the car and onto the scooter?

“I didn’t ditch the car completely,” he admits. “I don’t take the scooter in the rain, and I use the car when I absolutely have to – when I have too much to carry, for example.” But Hess admits that his compulsive New Yorker’s nature can’t abide waiting in traffic – “there, at least it moves; here, it seems to just stop” – and he found LA’s increasingly round-the-clock traffic jams more and more difficult to tolerate.

“What finally snapped my patience,” he says, “was when I had a client in Pacific Palisades with a very complicated land-use issue. There came a time when he couldn’t meet with me until 3 p.m. That evening, I had tickets to a classical concert downtown, and though I left the client at 5:00 p.m., I didn’t get home [to Hancock Park] until 8:15p.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests he’s not alone; Philharmonic officials have long fretted about falling concert attendance among Westsiders due in part to increasingly unmanageable cross-town traffic.

Hess is clearly infatuated with his two-wheel paramour, and eager to show her off.

“The old Vespas were built cheaply and tended to fall apart. They had little two-cycle engines, where you had to mix the gas and oil, and they required a great deal of personal attention to keep running.” As a kid, Hess had plenty of experience with a two-cycle Lambretta, Vespa’s primary competitor. “And if you didn’t get the mix right, ensuring that the engine got enough lubrication, you’d be riding along and the engine would basically seize up into a solid block of metal.”

Subsequent technical advances have largely eliminated that hair-raising possibility while increasing the scooter’s power. What’s more, operating costs are very low. Hess says that, after his roughly $7,000 initial investment, “in three years, I’ve only spent about $300 and tripled my fuel economy.”

So how does a white-collar professional manage to dress for the road and for the board room?

“When I have to meet someone, I get dressed up in layers—I wear well-protective motorcycle boots and stash my dress shoes under the saddle. On a hot day, I’ll put my suit jacket under the saddle and wear a leather jacket. I tried leather chaps once, but they were too uncomfortable.”

Hess concedes that earning a motorcycle license may not be for everyone, with the DMV requiring rigorous testing and training. Then comes the actual practice drills on busy metropolitan streets. Hess shudders at the memory. “You go through six months of absolute terror – Long Beach, Norwalk, Downey, Thousand Oaks. Lomita, Lennox, Hawthorne.” Today, he rides strictly on surface streets: “Although the Vespa technically is freeway legal, it’s totally crazy. I did it once for about 100 yards and got off.”

Cycling safety calls for constant vigilance. “Any kind of spill can be extremely painful,” Hess notes. “The first time I went down, I ripped my suit, and had bruises that took about a month to heal.”

Still, the upsides are considerable, including being able to score great parking spots. “The funny thing is in Italy, where they’re made, nobody rides them anymore – they’re too expensive.”

7 things you should know about the Westside Subway

October 31, 2009

With the Metro board’s recent approval of long range transportation projects for the region, the Westside Subway extension is embarking on an important new stage in its journey. With Santa Monica envisioned as the line’s ultimate destination, there is currently $4.1 billion in local funding, mostly from Measure R, to get it as far as Westwood. Federal dollars will be essential to finish the job.

Some critics of the proposed line argue that it will take too long to build, divert resources from other parts of the region and tunnel through some geological challenges. But proponents, including Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, an MTA board member, say the subway’s projected ridership success makes it the best bet for getting federal dollars, particularly since Measure R already is funding projects such as Expo Phase II, the Gold Line/Foothill extension and the Crenshaw Transit Corridor.

Key decisions are still to come on design and technical matters; community meetings are taking place to help determine the placement of stations, and there’s a new video to promote the project (thanks to Steve Hymon for flagging this at Metro’s new blog, The Source.)

So even though the first phase of the project—to Fairfax–won’t be completed until 2019, it’s not too early to know what’s driving the train.

It will go where jobs are.

The Westside has hundreds of thousands of jobs in a relatively concentrated area—currently 429,000 of them, according to the latest mid-year forecast by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp.– and commuters who live in outlying areas where housing is more affordable will be able to take advantage of them. That will be a boon to area business owners who’ve long complained about difficulties in hiring and retaining workers frustrated with time-consuming commutes, says Jack Kyser of the Kyser Center for Economic Research, one of the forecast’s authors. A bonus: those jobs are the highest-paying in the county—averaging $66,497 a year. The area also is home to UCLA, the 7th largest employer in the region, with more than 28,000 faculty and staff members.

It will create jobs.

Thousands of jobs will be created. As a rule of thumb, the building trades industry estimates 6,000 construction- and construction-related jobs per $1 billion invested in a project. The exact number of jobs in the long run, however, is hard to predict because those initially hired could stay with the project for multiple years, thus driving down the overall job count.

It will benefit commuters throughout the county.

Metro estimates that 64% of the line’s benefits—a federal formula measuring ridership and time saved–would go to those outside the Westside, with the greatest benefit (22 percent) accruing to the San Gabriel Valley. Metro research shows that more than 310,000 people travel into the Westside from across the region each morning, while 137,000 others leave it and 88,000 travel within it. Meanwhile, UCLA, California’s largest university, is a major area-wide draw with nearly 38,000 students, and the subway extension also has the potential of boosting cross-town access to a variety of major cultural venues, from Disney Hall and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Royce Hall.

It will save thousands of hours in commuting time.

A hypothetical twice-a-day commuter from Koreatown to Westwood would get back the equivalent of eight days in saved commuting time each year by using the subway, according to Metro estimates. Someone commuting from Pasadena would save even more time–12 days a year. To put it another way, that Pasadena commuter currently spending 82 minutes to get from Pasadena to Westwood on public transportation would be able to make the one-way trip in just 50 minutes. “It actually shrinks the city, in a sense,” says David Karwaski, planning and policy manager in UCLA’s Transportation Services Department.

It will help LA to get a greater share of federal transit dollars.

Putting this project in the pipeline sets the stage for Los Angeles to get an allotment that’s more like the New York/New Jersey behemoth, shown in this Metro graphic representing 2010 federal funding for new transit starts. A far more robust showing is possible in the future now that the board has adopted its long range projects priority list. Move over, New York and Salt Lake City. Hello, Los Angeles.

It will help relieve overcrowding on the region’s busiest bus corridor, Wilshire Boulevard.

The Wilshire corridor is the most heavily used bus corridor in the County of Los Angeles, with some 70,000 boardings every weekday from downtown to Santa Monica. With tens of thousands of office workers pouring into the area each day, and bumper-to-bumper traffic at peak hours not only on Wilshire but on the Santa Monica Freeway, the project provides a new option for bus riders while also easing the overall traffic crunch.

It beats taking the 10.

Need we say more?

A creek runs through it

October 30, 2009

Bringing a creek back to life isn’t a job – it’s a commitment for all seasons.

And for the biologists, environmentalists and volunteers who’ve made it their mission to restore Topanga Creek, removing 26,000 tons of concrete and debris last year was just the beginning.

This fall, they’ve moved into planting mode, laying the groundwork—literally—for a rebirth of not just a creek but of an entire ecosystem.

The oaks, sycamores, cottonwoods and other California native plants are still going into the ground, but Rosi Dagit, the driving force behind the project, has seen enough to declare the process a success.“Beyond our wildest dreams, it worked,” says Dagit, senior conservation biologist with the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains. Dagit has spearheaded the creek restoration effort with a huge and varied array of supporting players that includes the Mountains Restoration Trust, the Temescal Canyon Association, TreePeople, the California Conservation Corps and a Sierra Club trail crew.

“It’s huge,” says Jo Kitz, co-executive director of the nonprofit Mountains Restoration Trust, praising Dagit’s tenacity. “I don’t know how many agencies she had to go through to get where we’ve gotten. Once it’s done, it’s just going be one of the brightest spots in the mountains.”

Although the project has been years in the making, progress has been dramatic lately. The first big test of the restoration effort came last winter, with the downpours of December.

Would Topanga Creek return to its natural flow, now that a 1,000-foot-long mound of debris had been leveled? Would the creek once again become a birth canal of sorts for endangered steelhead trout that once flourished in its waters?

Dagit and her team crossed their fingers, jumped in their cars and headed to the creek to see whether their carefully crafted plans would unfold in the natural world as they’d envisioned. They were awestruck.

“It was the coolest thing ever,” says Dagit. “We couldn’t cross the creek because the water level was so high. I was a little weepy.”

The massive project had, in fact, worked to send water racing again through a stretch of the creek that had been rendered largely dry by the concrete berm, originally built four decades ago to protect homes from canyon flood waters. Over the years, residents just kept piling it higher and higher. Tons of backed-up sediments from the berm had literally driven the stream underground. Over the course of the next few years, winter rains will continue the clean-up process, washing sediment out to the shore, Dagit says.

And the steelhead trout, which live in both fresh and salt water, will have a straight shot from creek to ocean—and a swimming chance to repopulate in far greater numbers. What’s more, new habitat has been created for other at-risk creatures, including pond turtles, two types of garter snakes, the California newt and an assortment of frogs.

In all, during three months last fall, 26,000 tons of dirt and debris were hauled away—all of it recycled except for 94 truckloads of hazardous soil. Native plants and trees were protected, and native lupines were planted. The total cost was about $3 million in government grants, including $450,000 from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s Third District funds.

Over the past year, monthly workdays have drawn volunteers to plant, water and weed. The Conservation Corps recently swooped in to pick up 30 tons of left-behind concrete and 10 tons of asphalt. A Sierra Club trail crew has chopped away invasive non-native plants like arundo.

“It’s an extremely big deal,” Ron Webster, leader of the Sierra Club’s Santa Monica Mountains trail crew, says of the project. “The creek is an incredibly important resource. It’s so rare to have a year-round creek running through the mountains and to the ocean.”

With the creek finally reconnected, the biologists are turning their attention not only to planting but to the progress of the steelhead trout.

Late last year, Dagit and her colleagues tagged 75 to 100 of the endangered fish to track their movements. An antennae was placed in the stream to register each time one of the tagged steelhead passed by on its way to or from Santa Monica Bay. (A warning to would-be poachers: there’s a $25,000 fine for removing steelhead from the creek.) This November, Dagit and her 10-person team are going to hand-capture fish and compare scale samples with those taken last year — an unprecedented way to document the age and growth rate of steelhead in this location.

Eventually, the heavy work of planting will be completed and the focus will shift to another huge undertaking: the clean-up of Topanga Lagoon. But there are moments, as the seasons march by, when Dagit can’t resist stopping to savor the satisfaction of all that’s already been accomplished.

“I actually can’t believe we really did this,” she says. “I’m still pinching myself.”

Stepping up oversight for troubled children

October 30, 2009

In the wake of several high-profile deaths, the Board of Supervisors has taken steps to improve investigations and accountability at the Department of Children and Family Services and other agencies that intersect the lives of vulnerable youngsters. Two of those measures are focused on technology as a way to strengthen management oversight and improve communication among county agencies. A third aims to improve the diagnostic and forensic examinations of children allegedly abused or neglected.

In the wake of several high-profile deaths, the Board of Supervisors has taken steps to improve investigations and accountability at the Department of Children and Family Services and other agencies that intersect the lives of vulnerable youngsters. Two of those measures are focused on technology as a way to strengthen management oversight and improve communication among county agencies. A third aims to improve the diagnostic and forensic examinations of children allegedly abused or neglected.

Improved Communication: The supervisors, led by Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich, directed county agencies to immediately start feeding information into and using a computer database created years ago to help social workers with child abuse and neglect investigations. A number of county agencies have not been participating in the system, called the Family and Children’s Index (FCI), as they’d previously agreed to do. Although in place for more than a decade, FCI has been “woefully underutilized,” says Yaroslavsky. But now the agencies have signed memos of understanding, and this month (November), all seven agencies directed to use FCI will ramp up toward full employment of the information-sharing system.

Enhanced Accountability: A new, automated alert system called SafeMeasures will allow DCFS to keep its supervisors better informed of—and more accountable for—cases in which the department has received multiple abuse allegations against a single family. E-mails will be sent to higher ups in the Emergency Response chain of command, for instance, when three or more referrals come in about the same family or when two are received in the same year. Similarly, when social workers determine that a preliminary investigation does not warrant opening a full-blown case, two layers of Emergency Response supervisors will be required to sign off. In addition, supervisors must be notified if social workers have not started an investigation within 15 days after DCFS receives an abuse or neglect allegation.

Broadened Medical Exams: To ensure thorough medical and psychological evaluations of potential victims of child abuse or neglect, the supervisors voted unanimously to look into expanding the categories of children who can be examined by the county’s own medical and psychological experts through the County’s Medical Hub system. Currently, these expert medical and mental health exams are available at the Hubs only after county officials have opened a dependency court case for a child based on suspected abuse or neglect. The new proposal would expand the rules to allow the Hub-based experts to examine children at the earliest stages of an investigation, giving social workers key information to help determine whether to file a case. At present, parents often pick local doctors to examine their children who may not have training in recognizing child abuse or neglect. The change might add another 23,000 exams at the Hubs, more than doubling the current 17,000 according to DCFS. Separately, the board wants to expand the county’s ability to perform forensic psychological and medical examinations of children for use in court cases. The plan would station forensic experts throughout all seven Hubs in the county, shortening travel times for traumatized children.

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information