What’s at stake

April 5, 2011

My first day in Nigeria as part of the NDI election observer team has consisted of intensive briefings—eight of them—on the upcoming presidential contest. We’ve heard from non-partisan citizen election monitoring groups, local civil organizations, journalists, government security personnel and others.

My first day in Nigeria as part of the NDI election observer team has consisted of intensive briefings—eight of them—on the upcoming presidential contest. We’ve heard from non-partisan citizen election monitoring groups, local civil organizations, journalists, government security personnel and others.

Our delegation is an impressive group. It is led by former Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark, former New Jersey Governor John Corzine and former President of Niger Mahamane Ousmane, among others. There are several delegates from Europe and Australia. And there are a number from the African continent itself—from Ghana, Cameroon, South Africa, Kenya and Benin.

The delegation also has a contingent of observers from emerging democratic nations, including the vice chair of a political party in Egypt. During the uprising, he spent 18 days in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. He’s in Nigeria not only to monitor the election, but to look for lessons he can apply to the first potentially free elections in Egyptian history.

Although the Middle East and North Africa have gotten virtually all the headlines in recent weeks, the stakes in West Africa are high, as well. In Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), for example, the duly defeated incumbent president has refused to leave office, resulting in massive violence and nearly 1,000 deaths in recent days.

Still, the elephant in the electoral room is Nigeria.

At 165 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and it has had a checkered political history since gaining independence from Great Britain more than half a century ago. Almost three decades of military rule came to an end in 1999, when Nigeria undertook the first of several attempts to democratically elect its leaders.

At 165 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and it has had a checkered political history since gaining independence from Great Britain more than half a century ago. Almost three decades of military rule came to an end in 1999, when Nigeria undertook the first of several attempts to democratically elect its leaders.

That first election was not a confidence builder, and those that followed, in 2003 and 2007, had increasingly more problems. Indeed, NDI concluded that the 2007 election did not reflect the will of the Nigerian people. So, as one of our briefers told us, “We need to get this election right.”

There’s a herculean effort underway to make that happen. And there’s a lot riding on it not only for Nigeria but also for its West African neighbors and beyond. That’s why it’s being closely watched across the African continent.

Already, however, problems have arisen.

To start, election laws were passed so late by the national legislature that many people closely involved in the process have been unable to get a current copy of them. Then, ballots and other election materials were not delivered to polling places on time for the assembly elections, forcing officials to delay them a week. As a result, the presidential election, scheduled for next Saturday, will not be held until April 16.

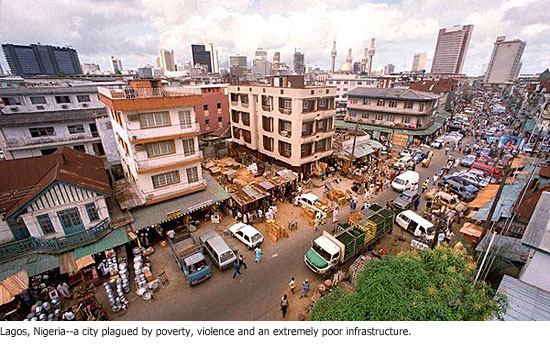

Then there are the practical issues, such as the nation’s waning infrastructure. One of our briefers explained that some polling places are outdoors—“under a tree”—and when it gets dark, there’s no way to illuminate the polling site because there’s no electricity. The inferior roads, meanwhile, make it difficult to move election equipment and materials to their destination. Information technology and access to the Internet are not as universal as back home. In short, this is a challenging place to run a smooth and transparent election for upwards of 75 million voters.

Yet the will of the Nigerian people to pull this off is palpable. There will be upwards of 40,000 Nigerian observers watching the 120,000 polling locations on election day.

One of the most sophisticated efforts to avoid the failures of the past comes from an organization called “Project 2011 Swift Count.” To guard against vote tallies changing between polling places and regional tabulation centers (a problem in the past), “Swift Count” will monitor

counts at their origins and shine a light on any efforts to “modify” them along the way.

For information on what these civil organizations are doing in this election, go to their website at Nigeriawatch2011.org.

What’s so moving and inspiring about all this is the awesome courage and commitment that these practical idealists possess. It even made me forget that my suitcase didn’t arrive here in Abuja.

We take our democracy so much for granted that we often forget how special and fragile this form of government can be. As Americans, we benefit from the spread of democracy around the world. But the principal beneficiaries are the emerging democracies themselves.

Photos by Zev Yaroslavsky

Posted 4/5/11

Observing history in Africa

April 5, 2011

Once again, Nigeria is at a turning point in its democratic evolution. And I’m there to monitor its elections as part of an international delegation headed by the Washington-based National Democratic Institute.

Once again, Nigeria is at a turning point in its democratic evolution. And I’m there to monitor its elections as part of an international delegation headed by the Washington-based National Democratic Institute.

Time and technology permitting, I’ll be documenting my experiences in words and pictures on a special page on my website called Nigerian Chronicles. Please join me there for an up-close look at this troubled nation’s quest for self-governance.

Posted 4/5/11

An election challenge in Africa

April 5, 2011

I got the word Sunday afternoon at LAX as I was getting ready to board a plane to Nigeria: the African nation’s presidential election—for which I was to be an observer—had been delayed.

I got the word Sunday afternoon at LAX as I was getting ready to board a plane to Nigeria: the African nation’s presidential election—for which I was to be an observer—had been delayed.

The problem was that ballots and results sheets for an earlier scheduled parliamentary election did not arrive on time, meaning both elections would now have to be pushed back one week. As the head of Nigeria’s election commission put it: “We cannot bury our heads and say there are no problems. It’s regrettable. It is unfortunate. It should not have happened.”

These postponements illustrate the kind of mess Nigeria’s electoral process is in—and the challenging organizational issues and logistics election officials there continue to confront. They had originally planned to delay the parliamentary elections for only two days but then wisely decided they needed a full week to get their act together.

So, next Saturday, Nigeria will hold its parliamentary elections. And I’ll be on the ground with the rest of the international delegation assembled by the Washington-based National Democratic Institute, a non-governmental organization that, among other things, monitors elections in emerging democratic nations.

At NDI’s direction, we’ll be monitoring next Saturday’s parliamentary elections because the organization believes they’ll foreshadow the issues likely to be encountered during the presidential election, now scheduled for the following weekend.

We shall see.

Posted 4/4/11

On the road with history

April 5, 2011

Next week, I’m off to Nigeria as part of a delegation of election observers to monitor that deeply troubled nation’s April 9th presidential contest.

Next week, I’m off to Nigeria as part of a delegation of election observers to monitor that deeply troubled nation’s April 9th presidential contest.

I’ll be traveling with the Washington-based National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), an internationally respected non-governmental organization that, among other things, monitors elections in emerging democratic nations and advises their leaders on issues of governance.

Under NDI’s umbrella, I’ve conducted seminars on local government finance in Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Bosnia-Herzegovina. I’ve also observed elections in Romania (1990), Mexico (2000) and Ukraine (2004).

I’m proud to say that I’ve worked with the group for more than two decades as a pure labor of love. My only compensation has been the opportunity to help the courageous people of these countries in their high-stakes push for self-governance.

In Romania, those stakes were about building a democracy while the wounds of the Ceausescu regime were still raw.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, it was about trying to bring together people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds to create civic institutions and a civil society after a brutal war had ravaged the new nation.

In Mexico, it was about conducting the country’s first free and transparent election in 70 years, which resulted in the defeat of the party that, until then, had dominated its politics and controlled its government.

And in the Ukraine, those stakes were about nothing less than the first peaceful and democratic transition of power in that nation’s history.

As for Nigeria—Africa’s most populous nation and one of the world’s poorest—the situation is far less settled. The nation has struggled for more than a decade in the transition from military dictatorial rule to a democratically elected civilian government. The last three elections were plagued by violence, murder, kidnappings and chaos. Still, with courage and persistence, the Nigerian people have kept alive their dream of a government of the people, by the people and for the people.

Election observation has been one of the great highlights of my life, an experience I’ve chosen over taking vacations. Although the days and nights are long, my fellow observers and I have the privilege of being participants in history. The people we meet, the cultures in which we become steeped and the democratic outcomes we help birth, make the experience singularly rewarding.

Next week, time and technology permitting, I plan to share my experiences with you on my blog. I also hope to post photographs and video from Nigeria. So stay connected to this site and be a witness to history yourself.

Son of former supe an open book

April 1, 2011

Novelist and poet Tom Schabarum says people had his dad all wrong.

Novelist and poet Tom Schabarum says people had his dad all wrong.

Yes, former Supervisor Peter F. “Pete” Schabarum famously locked horns with the gay community in the mid-1980s over funding for the rapidly escalating AIDS epidemic. But, Tom says, he was not anti-gay, as the critics alleged.

The son says he should know. Twenty-two years ago, while walking along the beach with his father in San Diego, he shared a secret.

“I came out to him,” Tom Schabarum recalls. “We talked for many hours. And he was great. He was awesome. He basically said, ‘This is not going to change our relationship,’ but in fact it did. It made it really, really good.”

These days, Tom is far removed from quiet talks on the shoreline. With his 50th birthday approaching, he’s now a Seattle writer whose debut novel, “The Palisades”, has just been named a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award, which recognizes gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) writing nationally. Last year, his poetry won the Creekwalker Poetry Prize, and this month, he completed a third work of fiction.

No, he laughs, none of it is subconsciously about his father. In fact, “The Palisades” began as an exploration of his relationship with his mother, Gerry, who died at 70 in 2007. He speaks several times a week to his beloved dad, who is now 82 and living near Palm Desert. He rarely discusses their relationship, he says, simply because for them, his coming out is “old news.”

“But I understand how it might come up,” he says, when asked. And for those who wonder how a gay son relates to a father whom gay activists once viewed as a public enemy, his response is ready: “My dad and I have always been great friends, and continue to be.”

Pete Schabarum was a Los Angeles County Supervisor for nearly two decades; a 640-acre wilderness park in the San Gabriel Valley is named after him. A real estate developer from Covina and one-time professional football player for the San Francisco 49ers, he was elected to the state assembly in 1966, then appointed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1972 to fill the First District seat of the late Frank G. Bonelli.

His tenure was a time of immense social change in Los Angeles County. By 1980, Reagan was in the White House, and the elder Schabarum was part of a conservative board majority. Small government was the watchword, but profound challenges were testing the county. In 1985, as activists became increasingly militant in their calls for more AIDS prevention funding, the state’s AIDS advisory board accused L.A. County of dragging its feet on a public health crisis. From now on, the board said, the state should give its money directly to community AIDS organizations rather than trusting the county to control the purse strings.

Offended, Pete Schabarum took aim at some of those local organizations, and when he denounced one particularly explicit safe-sex brochure as “plain, hard-core pornography,” the remark, picked up in Time magazine, turned the supervisor himself into a target. Positions hardened, and in 1989, after an especially noisy demonstration by AIDS activists in the board chamber, he angrily told them: “If you were to poll the man in the street, I think you would find the vast majority of the public really has no interest in the subject of AIDS and certainly could care less about the public financing the needed programs that you have articulated.”

Such remarks, Tom Schabarum says, stemmed from outrage at the demonstrators, not from a lack of concern about AIDS. The younger Schabarum says 1989 was the year he came out, and the criticism “was a real bummer for me because I knew he wasn’t homophobic.”

Such remarks, Tom Schabarum says, stemmed from outrage at the demonstrators, not from a lack of concern about AIDS. The younger Schabarum says 1989 was the year he came out, and the criticism “was a real bummer for me because I knew he wasn’t homophobic.”

Two years later, demographics eclipsed that battle. As pressure built in L.A. for more diverse representation, a court ordered redistricting gave Latinos a greater voice in the selection of a supervisor. As a result, Pete Schabarum retired from his First District seat and was succeeded by current Supervisor Gloria Molina.

“I think my dad was a politician for noble reasons,” says the younger Schabarum. “Whether he was conservative or liberal doesn’t make any difference—he wanted to do good.”

Growing up, he says, his father’s support was a given. When Tom, at 20, caught the photography bug, he says, his father never questioned his request to transfer from the University of Utah, where he was an English major. “I don’t know what my parents said to each other, but when I said, ‘Hey, Dad, I want to go to photography school, he just said, ‘Okay’.”

The younger Schabarum eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in cinematography from the Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara and went to work for firms that stage live corporate events such as sales meetings and product launches. He is still a freelance creative director and producer with clients ranging from banks to major tech companies.

But writing remained a passion, and in the early 1990s, he says, he began his first novel, a family drama about a gay son and his vagabond mother in Big Sur.

“The book stemmed from wanting to connect with my own mother, but it’s not autobiographical at all—in fact my mother is not even in the book and Nicholas [the gay character] bears no resemblance whatsoever to me.”

He worked on it, he says, during a workshop taught by L.A. author and former USC instructor John Rechy, and when he finished after four years, “I put it in a drawer and started another novel.” That book, “The Narrows, Miles Deep,” depicted another family, this time during the AIDS crisis, and it went into the drawer, too.

“I was writing for myself—I never felt like I was writing to publish,” he says. In fact, “The Palisades” stayed in the drawer for 12 years, through a third novel, countless poems and an MFA in creative writing from Bennington College.

“But then I went through a midlife crisis or whatever, and decided that if I wanted to be viewed as a writer, I needed to put my work out there,” he says. One day, he described the manuscript to a writer friend in Seattle, and, on the friend’s advice, decided to test the waters by self-publishing on Kindle in the hope of attracting a mainstream publisher’s attention.

The result was the announcement last month that “The Palisades” has been named a finalist in the category of gay debut fiction. (The poem below is available in the upcoming issue of “Poet Lore” magazine.) “I’m finally coming out—as a writer,” he says, laughing.

“I have so many more stories to tell.” The awards will be presented May 26 in New York.

Posted 3/30/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink