Nigerian Chronicles

Democracy and the human spirit

April 14, 2011

There’s a certain conventional wisdom that Third World countries can’t understand or handle democracy. But anyone who harbors such notions has not witnessed, as I did last week, the people of one such nation, Nigeria, calmly standing in line for hours in the brutal heat to cast ballots in the exercise of self governance.

There’s a certain conventional wisdom that Third World countries can’t understand or handle democracy. But anyone who harbors such notions has not witnessed, as I did last week, the people of one such nation, Nigeria, calmly standing in line for hours in the brutal heat to cast ballots in the exercise of self governance.

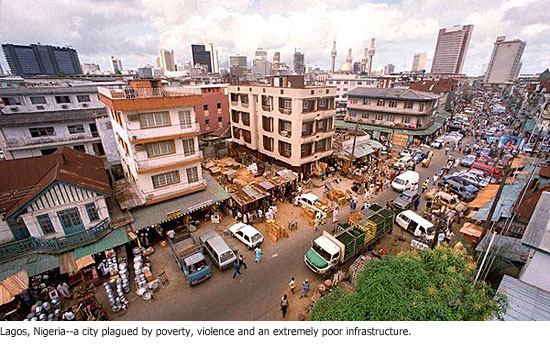

Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria is ravaged by poverty. Still, its residents just participated in arguably their nation’s most successful national assembly elections. This weekend, they’ll turn out en masse to elect a president with hope and pride.

Now that I’ve returned to the world of technology, I’ve downloaded some pictures and video I shot during my week in Nigeria as an election observer with the Washington-based National Democratic Institute. I hope they give you a sense of the passion that millions of people beyond our own borders hold for the development for democracy in their lands.

Counting the votes: A video by Zev of ballots being tallied in Iolin, the capital of Kwara state.

Posted 4/14/11

Dispatches from a democracy in progress

April 11, 2011

Election day, Saturday, started ominously. The night before, a terrorist bomb exploded in the city of Suleja, 12 miles from the nation’s capital, Abuja. At least 13 people were killed. There were several other incidents Friday night that were obviously designed to disrupt the election. It didn’t work.

Election day, Saturday, started ominously. The night before, a terrorist bomb exploded in the city of Suleja, 12 miles from the nation’s capital, Abuja. At least 13 people were killed. There were several other incidents Friday night that were obviously designed to disrupt the election. It didn’t work.

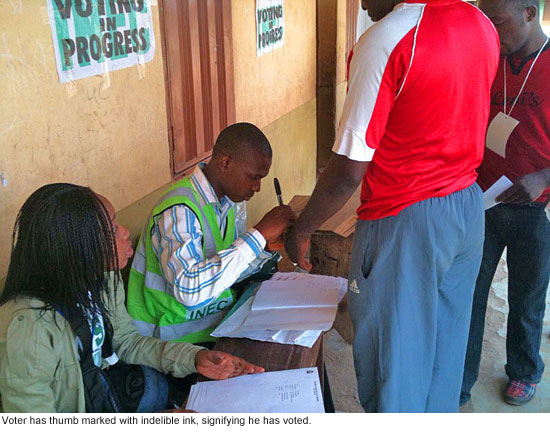

The election appeared to be an improvement over previous national elections here. To be sure, there were problems. It took hours in the a.m. for people to check in, and then several more hours in the p.m. for voters to cast their ballots. All voting was outdoors, and it was hot and humid. I was wiped out, and I had an air conditioned car to which to escape. I can’t imagine what women with babies on their backs were going through, standing for hours at a time. These waits created some episodic tension.

Other problems our delegation witnessed included under age voting, missing names on voter registration rolls, late opening of many polling sites, inconsistency in the posting of the results at polling stations, inconsistency in the application of election laws and rules, and a lack of prioritization for the elderly, disabled and pregnant women or other women who brought their youngsters to voting stations. All these concerns were addressed in a preliminary report released by our NDI delegation.

Nevertheless, we thought that Nigeria took a positive and necessary step toward the building of a sustainable democracy and strong democratic institutions. Voters came by the hundreds to each polling station, determined to make this election work. Many hung around all day in the oppressive weather and into the dark evening to observe the vote count.

An especially moving part of election day came at the end, when ballots were tabulated at polling stations. We chose one at random to monitor in the central part of Ilorin, the capital of Kwara state, where we were deployed. A crowd of nearly 100 partisans of various parties gathered to observe the count at this precinct, a scene repeated at thousands of polling places around the country.

Afer each ballot was retrieved from the ballot box, the precinct officer would show it to the assembled crowd and announce the chosen candidate. Cheers would arise from the partisans in the crowd. When the vote’s final result was announced, the winning side not only cheered but started dancing in the street. It was an exhilarating end to a very long day. The results were then posted (at our polling station, at least), and the ballots were transported to the election commission headquarters for the official election report.

Afer each ballot was retrieved from the ballot box, the precinct officer would show it to the assembled crowd and announce the chosen candidate. Cheers would arise from the partisans in the crowd. When the vote’s final result was announced, the winning side not only cheered but started dancing in the street. It was an exhilarating end to a very long day. The results were then posted (at our polling station, at least), and the ballots were transported to the election commission headquarters for the official election report.

As we concluded our election day activities, I asked my observation partner, Jennifer Cooke, director of the Africa program for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, what are the American national security interests in Africa. She said that the three principal interests are:

1. Corrupt regimes and/or political instability are fertile breeding grounds for extreme ideologies and movements that manifest themselves in ways that are inimical to our interests.

2. Energy. Nearly 25% of our imported oil now comes from Africa, 9% of it from Nigeria itself. Political stability is, therefore, in our best interest. Instability can cause the price of energy to fluctuate and supplies to diminish. And energy uncertainty has its own national security issues for us.

3. In the increasingly globalized nature of our economy and other national policies, we will increasingly depend on coalitions with and support of the many nations on this African continent to join with us in various international forums as we address issues such as trade and terrorism.

Simply put, Nigeria is the biggest nation on the African continent. Any failures there could easily spread to the rest of West Africa and beyond. This would not be good for them or for us. To paraphrase the late German statesman Klemens von Metternich, if Nigeria sneezes, the rest of Africa could well catch a cold.

So our election monitoring delegation leaves Nigeria tonight with the satisfaction that this country got a lot right in its election, but tempered by the reality that it has a long way to go.

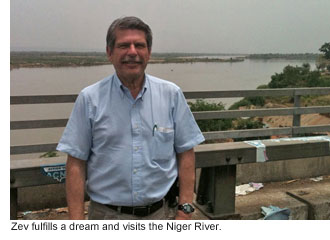

On a personal note, I did get my chance to see the Niger River today, a body of water that has intrigued me since my days as a graduate student at UCLA in British Imperial history. We drove back to Abuja, an eight hour drive of 300 miles. The roads are, to be blunt, horrible—two lanes all the way, with missing chunks of road every now and then that makes driving them time consuming and dangerous. Overturned trucks, including huge gasoline trucks, abound along the roadsides, crashed and abandoned by their drivers. As one local described it: ”Driving in Nigeria is a competition among drivers. Some win, and some don’t.”

About six hours into the drive we approached the bridge over the Niger. I asked our driver to stop so I could take a closer look and give me and the river a chance for our photo op. I never thought I’d have this chance, and yet here I was.

To those of you who have been following my blogs from Nigeria, thank you. I’ve enjoyed sharing this experience—both the policy and personal sides. As I prepare for my 22 hour trip home, I confess that I’ll be sorry to leave. The people have been wonderful, and I won’t soon forget their courage and resilience. I wish them well on their march toward sustainable democracy, a march that all of us should support, not only because it’s in our best interests, but because it’s right.

Photos from Zev Yaroslavsky

Posted 4/11/11

On the eve of the vote [updated]

April 8, 2011

Tomorrow is Election Day in Nigeria.

Tomorrow is Election Day in Nigeria.

So today I’m crisscrossing the capital city of Nigeria’s Kwara state, Ilorin, with my partner, Jennifer Cooke, of the Washington-based Center for Strategic Studies. We’re visiting political party officials, journalists, the election commission chairman for Kwara state (who’s got a big job), and local government officials, among others.

Our goal is to gather as much intelligence and ground-based information as we can on what folks think will happen when Nigerians head to their polling places on Saturday. We want to know where, if anywhere, trouble or problems are expected. Jennifer, John (our local chaperone) and I will aggregate that information tonight and chart our observation route. We’ll hit the road at dawn, visiting polling places to observe how the process is working, including whether ballots and other vital election materials have arrived on time and whether people are able to check in and vote without any major hiccups.

As we work through our route, we’ll also decide what specific polling station we’ll track to the next level—the regional tabulation center, which is the equivalent of our voter registrar’s office—to make sure the counts are the same in both locations.

All this is a time consuming and physically taxing process, and we’ve gotten little sleep. The good news is that Jennifer is a sub-3:20 marathoner and I do my share of running, too. So our stamina is holding up in the tropical heat.

(A sidebar to all this is that Jennifer was scheduled to run the Boston marathon the week after next, but she’s staying in Nigeria to monitor the postponed Presidential balloting a week from tomorrow. Now, that’s commitment to Nigerian democracy.)

A few observations of Ilorin and its environment:

Nigeria is one of the poorest nations on the globe, and that was evident on our drive in from the airport. For the vast majority of locals, life is rudimentary at best. By our standards, one would characterize the population as economically poor. We are told that there’s a small but growing middle class, but it’s hardly noticeable. Then there’s the large concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Their homes, or estates, would be the envy of Beverly Hills or Bel Air. Incredibly, one home has its own mosque on the front of the property.

In much the same way that race influences interpersonal relations in the U.S., religion and tribal rivalries can often divide Nigerians. Kwara state is majority Moslem with a significant, but decidedly minority, Christian population. There are two tribes that dominate here—the Yoruba and the Hausa-Fulani. Their languages are distinct and utterly unrelated to each other. There’s no reticence of either to stereotype the other.

This sort of thing always makes me nervous because of where it can lead. Those of us who are old enough to remember can recall the civil war with Biafra in the late 1960′s, when tens of thousands civilians were killed and millions of the defeated Igbo tribe were rendered refugees.

In short, this election represents another threshold moment in the evolution of civilian and democratic government in this, Africa’s most populous nation. No one expects the election will go perfectly. Few ever do in emerging democracies. It will be a success, though, if there’s a marked improvement over the last three national elections in 1999, 2003 and 2007. Success will be an election with minimal violence and a credible result, based on a smooth and transparent process that allows Nigerians to elect and believe they have elected candidates of their own choosing.

If Nigeria can pull this off, it will help build public confidence in the institutions vital to any sustainable democracy. This is a building block in the construction of that democracy. They have a long way to go, but there are a lot of Nigerians determined to get there.

You will next hear from me after the election, most likely after the National Democratic Institute has debriefed its observers back in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, on Sunday and Monday. Then, I’ll be headed home to turn my attention back to our own county and my new granddaughter.10

Updated 4/8, 10 p.m.: Sadly, a bomb exploded Friday at the Independent National Electoral Commission office in Suleja in central Nigeria, according to media reports, including this one from CNN. Eight people reportedly died in the attack, the latest in a series of violent acts aimed at derailing democracy in Nigeria.

In Kwara state, where I’m observing the national elections, there has been no reported violence or a history of the kind of deadly attacks that have erupted elsewhere during the past two days. So forward we move.

Photos from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky

Posted 4/8/11

On our way into the countryside

April 6, 2011

My second full day in Abuja, Nigeria, was filled with more intense briefings on this nation’s political and religious scene, preparatory to our delegation’s deployment on Thursday to various parts of the country.

My second full day in Abuja, Nigeria, was filled with more intense briefings on this nation’s political and religious scene, preparatory to our delegation’s deployment on Thursday to various parts of the country.

We met with Nigerian religious leaders today, including the Catholic Archbishop of Abuja and the Imam of the national mosque here. Nigeria is a nation that is almost evenly divided between Moslems, mainly in the north, and Christians, mainly in the south. The clergy play an important role in trying to keep political discourse as civil as possible.

We also had a fascinating briefing from the “Independent National Election Commission,” which is charged with the responsibility of pulling together these elections (legislative, presidential and gubernatorial) in the days and weeks ahead.

Aspects of the voting process here are much different than what we’re used to at home. For example, voters who want to cast ballots must arrive at the polling place between 8:00 a.m. and noon to sign up. Once everyone has had their identity validated and their registration verified, they must wait until 12:30 p.m. to start voting.

Thus, hundreds of people at each polling station will be stuck for several hours before casting a single ballot—with temperatures in the high 90′s and humidity to match. (The reason for this process, we’re told, is to prevent people from going from one polling place to another and casting multiple votes—a problem that has plagued past Nigerian elections. The theory is that a person can only be at one polling place at the prescribed time of 12:30.)

The last set of briefings today was about security—both for the election and for our observer team. Violence has been an unfortunate part of the Nigerian political landscape for decades. Disruption of polling stations, intimidation and worse have been used by some parties in some states to diminish their opposition’s vote and turnout, thus improving the perpetrators’ electoral prospects. Moreover, kidnapping, robbery, murder and even roadside bombs have been employed in certain states. We’ve been given the “do’s and don’ts” to minimize our own vulnerability.

Tomorrow, I leave for Kwara state with my monitoring partner, Jennifer Cooke, director of the African program at the Washington-based Center for Strategic Studies. There, about a five-hour drive west of Abuja, we’ll meet with local stakeholders, party reps, journalists and leaders of non-partisan civil society tomorrow and Friday.

On Saturday, we’ll cover as many polling stations as we can reach to determine whether the election in this state is credible, or whether irregularities bring its validity into question. More than 20 teams like mine will fan out across Nigeria to do exactly the same thing. On Sunday, we’ll reconvene in Abuja to debrief. Then based on the report of all of our teams, NDI will issue a statement evaluating the transparency and fairness of the election.

Essentially, we and the thousands of other observers who have descended upon this nation will help bear witness to whether the Nigerian people have been able to elect representatives of their choosing.

Finally, I look forward to crossing and seeing the Niger River for the first time. The Niger has been the lifeblood of West Africa since human time began in these parts. This mother of a river has intrigued me since my UCLA days as a graduate student in British Imperial History.

I’m signing off for now. The next three days will be memorable, no matter what happens. They’ll also be work intensive and time consuming. I’ll do my best to share my experiences, but I may miss a day or two.

Posted 4/6/11

What’s at stake

April 5, 2011

My first day in Nigeria as part of the NDI election observer team has consisted of intensive briefings—eight of them—on the upcoming presidential contest. We’ve heard from non-partisan citizen election monitoring groups, local civil organizations, journalists, government security personnel and others.

My first day in Nigeria as part of the NDI election observer team has consisted of intensive briefings—eight of them—on the upcoming presidential contest. We’ve heard from non-partisan citizen election monitoring groups, local civil organizations, journalists, government security personnel and others.

Our delegation is an impressive group. It is led by former Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark, former New Jersey Governor John Corzine and former President of Niger Mahamane Ousmane, among others. There are several delegates from Europe and Australia. And there are a number from the African continent itself—from Ghana, Cameroon, South Africa, Kenya and Benin.

The delegation also has a contingent of observers from emerging democratic nations, including the vice chair of a political party in Egypt. During the uprising, he spent 18 days in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. He’s in Nigeria not only to monitor the election, but to look for lessons he can apply to the first potentially free elections in Egyptian history.

Although the Middle East and North Africa have gotten virtually all the headlines in recent weeks, the stakes in West Africa are high, as well. In Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), for example, the duly defeated incumbent president has refused to leave office, resulting in massive violence and nearly 1,000 deaths in recent days.

Still, the elephant in the electoral room is Nigeria.

At 165 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and it has had a checkered political history since gaining independence from Great Britain more than half a century ago. Almost three decades of military rule came to an end in 1999, when Nigeria undertook the first of several attempts to democratically elect its leaders.

At 165 million people, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and it has had a checkered political history since gaining independence from Great Britain more than half a century ago. Almost three decades of military rule came to an end in 1999, when Nigeria undertook the first of several attempts to democratically elect its leaders.

That first election was not a confidence builder, and those that followed, in 2003 and 2007, had increasingly more problems. Indeed, NDI concluded that the 2007 election did not reflect the will of the Nigerian people. So, as one of our briefers told us, “We need to get this election right.”

There’s a herculean effort underway to make that happen. And there’s a lot riding on it not only for Nigeria but also for its West African neighbors and beyond. That’s why it’s being closely watched across the African continent.

Already, however, problems have arisen.

To start, election laws were passed so late by the national legislature that many people closely involved in the process have been unable to get a current copy of them. Then, ballots and other election materials were not delivered to polling places on time for the assembly elections, forcing officials to delay them a week. As a result, the presidential election, scheduled for next Saturday, will not be held until April 16.

Then there are the practical issues, such as the nation’s waning infrastructure. One of our briefers explained that some polling places are outdoors—“under a tree”—and when it gets dark, there’s no way to illuminate the polling site because there’s no electricity. The inferior roads, meanwhile, make it difficult to move election equipment and materials to their destination. Information technology and access to the Internet are not as universal as back home. In short, this is a challenging place to run a smooth and transparent election for upwards of 75 million voters.

Yet the will of the Nigerian people to pull this off is palpable. There will be upwards of 40,000 Nigerian observers watching the 120,000 polling locations on election day.

One of the most sophisticated efforts to avoid the failures of the past comes from an organization called “Project 2011 Swift Count.” To guard against vote tallies changing between polling places and regional tabulation centers (a problem in the past), “Swift Count” will monitor

counts at their origins and shine a light on any efforts to “modify” them along the way.

For information on what these civil organizations are doing in this election, go to their website at Nigeriawatch2011.org.

What’s so moving and inspiring about all this is the awesome courage and commitment that these practical idealists possess. It even made me forget that my suitcase didn’t arrive here in Abuja.

We take our democracy so much for granted that we often forget how special and fragile this form of government can be. As Americans, we benefit from the spread of democracy around the world. But the principal beneficiaries are the emerging democracies themselves.

Photos by Zev Yaroslavsky

Posted 4/5/11

An election challenge in Africa

April 5, 2011

I got the word Sunday afternoon at LAX as I was getting ready to board a plane to Nigeria: the African nation’s presidential election—for which I was to be an observer—had been delayed.

I got the word Sunday afternoon at LAX as I was getting ready to board a plane to Nigeria: the African nation’s presidential election—for which I was to be an observer—had been delayed.

The problem was that ballots and results sheets for an earlier scheduled parliamentary election did not arrive on time, meaning both elections would now have to be pushed back one week. As the head of Nigeria’s election commission put it: “We cannot bury our heads and say there are no problems. It’s regrettable. It is unfortunate. It should not have happened.”

These postponements illustrate the kind of mess Nigeria’s electoral process is in—and the challenging organizational issues and logistics election officials there continue to confront. They had originally planned to delay the parliamentary elections for only two days but then wisely decided they needed a full week to get their act together.

So, next Saturday, Nigeria will hold its parliamentary elections. And I’ll be on the ground with the rest of the international delegation assembled by the Washington-based National Democratic Institute, a non-governmental organization that, among other things, monitors elections in emerging democratic nations.

At NDI’s direction, we’ll be monitoring next Saturday’s parliamentary elections because the organization believes they’ll foreshadow the issues likely to be encountered during the presidential election, now scheduled for the following weekend.

We shall see.

Posted 4/4/11

On the road with history

April 5, 2011

Next week, I’m off to Nigeria as part of a delegation of election observers to monitor that deeply troubled nation’s April 9th presidential contest.

Next week, I’m off to Nigeria as part of a delegation of election observers to monitor that deeply troubled nation’s April 9th presidential contest.

I’ll be traveling with the Washington-based National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), an internationally respected non-governmental organization that, among other things, monitors elections in emerging democratic nations and advises their leaders on issues of governance.

Under NDI’s umbrella, I’ve conducted seminars on local government finance in Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Bosnia-Herzegovina. I’ve also observed elections in Romania (1990), Mexico (2000) and Ukraine (2004).

I’m proud to say that I’ve worked with the group for more than two decades as a pure labor of love. My only compensation has been the opportunity to help the courageous people of these countries in their high-stakes push for self-governance.

In Romania, those stakes were about building a democracy while the wounds of the Ceausescu regime were still raw.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, it was about trying to bring together people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds to create civic institutions and a civil society after a brutal war had ravaged the new nation.

In Mexico, it was about conducting the country’s first free and transparent election in 70 years, which resulted in the defeat of the party that, until then, had dominated its politics and controlled its government.

And in the Ukraine, those stakes were about nothing less than the first peaceful and democratic transition of power in that nation’s history.

As for Nigeria—Africa’s most populous nation and one of the world’s poorest—the situation is far less settled. The nation has struggled for more than a decade in the transition from military dictatorial rule to a democratically elected civilian government. The last three elections were plagued by violence, murder, kidnappings and chaos. Still, with courage and persistence, the Nigerian people have kept alive their dream of a government of the people, by the people and for the people.

Election observation has been one of the great highlights of my life, an experience I’ve chosen over taking vacations. Although the days and nights are long, my fellow observers and I have the privilege of being participants in history. The people we meet, the cultures in which we become steeped and the democratic outcomes we help birth, make the experience singularly rewarding.

Next week, time and technology permitting, I plan to share my experiences with you on my blog. I also hope to post photographs and video from Nigeria. So stay connected to this site and be a witness to history yourself.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink