Drought reigns in plant kingdom

February 6, 2014

A volunteer helps plant one of 24,000 seedlings that have languished in a nursery because of drought conditions on hillsides charred by last year's massive Springs Fire. Photo/Steve Friedman

Last spring, after Sycamore Canyon was devastated by the earliest fire season in memory, Irina Irvine raced to protect the scenic landmark from an ancillary threat.

A restoration ecologist with the National Park Service, Irvine had been working to rid the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area of destructive non-native grasses. Some of her most successful work had been in the hills around Newbury Park, where, in May, the fire had started.

Knowing that opportunistic plants could retake and wreck the natural ecosystem if she didn’t act quickly, Irvine prepared 24,000 native seedlings—elderberry and oak, coastal sage and purple needle grasses. Then she waited for the winter rains, when the sprouts could be planted.

And waited. And waited.

“Twenty-four thousand plants at $3 a plant, and several interns hired especially for this,” says Irvine. “And it hasn’t rained yet.”

Lawns aren’t the only landscapes that are starting to feel the effects of this year’s extreme drought. From street medians to coastal canyons, local naturalists say the shortage of water is having all sorts of unprecedented impacts.

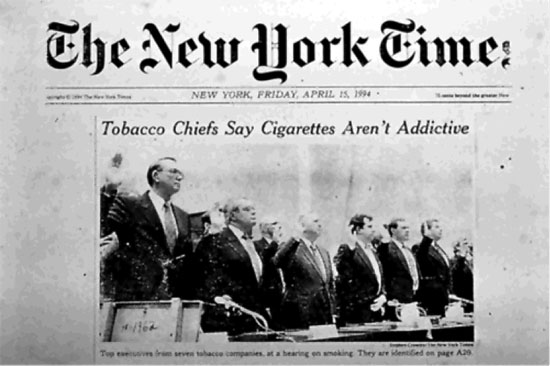

At the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, the absence of soil-cooling rain has tricked spring-blooming trees into blossoming as if it were April. In the San Fernando Valley, meanwhile, wildflowers are failing to germinate for lack of water.

In the Angeles National Forest, the drought has not only dried up natural springs but also emptied rain-catching “guzzlers”, small man-made reservoirs that provided a reliable fallback in past years for thirsty birds and wildlife. In the Santa Monica Mountains, the extreme water shortage has made historic oaks vulnerable to bark beetles and weakened even resilient trees such as eucalyptus.

“There’s been a lot of die-off in the native vegetation,” says Florence Nishida, a resident of Topanga Canyon and master gardener at the Museum of Natural History. “Landscaping at least has some source of water. But in the natural areas, the plants have gone since last March or April until now with hardly a drop of rain.”

Frank McDonough, botanical information consultant at the Arboretum, says the region is feeling a triple whammy—a years-long drought combined with a warmer-than-usual fall and winter and a high-pressure ridge that has cut off California’s usual dose of rain. Without a series of good, soaking downpours to cool down the soil, he says, the tree roots don’t realize it’s winter, and that, plus last month’s record heat, has left plants confused.

“Now our pink trumpet trees, which usually don’t bloom until March, are covered in blossoms, and the flowering apricots and nectarines are starting to bloom,” says McDonough, adding that more than a year or two of such unusual conditions can weaken trees and leave them vulnerable to disease and insects. Although it’s not necessarily good news, he says, “I expect the cherries will bloom earlier than normal, too.”

In wildflower country, on the other hand, the lack of rain is just depressing.

“It’s been pretty pitiful for the past two years, and it will probably be the same or worse this year,” says Lili Singer, director of special projects and adult education at the Theodore Payne Foundation, a Sun Valley nonprofit that operates an annual wildflower hotline.

For a good show, she says, wildflowers need at least one serious rain per month, starting in the autumn, so that they can establish themselves and produce plenty of buds before they start flowering. But with the exception of man-made seed-sowing initiatives such as Wildflowering L.A.—whose gardeners have been forced to water their supposedly drought-tolerant seedlings far more than expected—and the possibility that a few rare species will sprout in the wake of recent brush fires, Singer and other naturalists say they don’t have high hopes for this season.

“There’ll always be something for people to see,” says Singer, “but it will be a lot lower in the number of plants and the diversity.”

Nor are the wildflowers the only living things that are thirsty. In the Angeles National Forest, for instance, the county this week approved a grant to repair watering stations for wildlife and birds.

“This drought has just been real tough,” says John Forgy of the San Gabriel Valley chapter of Quail Forever, an organization that has offered to make the repairs as part of its work supporting wildlife. “And some of the young birds only eat insects, and there are no insects if there’s no rain.”

Irvine of the National Park Service says she has seen all these drought symptoms and more in the Santa Monica Mountains, where, in the plant world at least, “everything’s a little wacky right now.”

Vegetation, she notes, is vital in wildlands, not only because it’s habitat for wildlife, but also because it prevents erosion and counteracts global warming by sequestering carbon dioxide.

In areas like the mountains, where many species have evolved around drought, a dry year or two isn’t necessarily alarming.

“But you can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” says Irvine. “When I see a big eucalyptus that’s been here for 50 years dying because there’s no water, that catches my attention. Pine trees are being hammered. And we are already seeing significant die-back in chaparral communities, and we don’t know if they’ll pop back up again if it rains, or if, when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Particularly unnerving has been the effort to restore those 10 acres near the Wendy Trail head near Newbury Park at Rancho Sierra Vista in an area that was consumed last May during the freakishly early Springs Fire. Fueled by Santa Ana winds that had sucked the humidity in the air down to the single digits, the blaze swept from the canyons to the surf, consuming some 24,000 acres of drought-dried Los Angeles and Ventura Counties.

Among the casualties were some of the most scenic spots in the Santa Monica Mountains, including acreage on which Irvine had spent months trying to eradicate a particularly toxic and invasive strain of Australian bunch grass. The plan was to replant the area as quickly as possible with native seedlings that Irvine had carefully sprouted and set aside in a nursery.

“Normally what one does is wait for the first soaking rain of the year and then run, quick like a bunny, to get the plants in the ground as soon as the soil softens,” says Irvine. She had banked on an autumn planting. “But then when it didn’t rain in October, we were, like, ‘Darn it’,” she says. “And then no rain again in November. Darn it. And then December. And it was, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

The longer they waited, she says, the harder the earth got, making it even more difficult to transplant the seedlings that were in the nursery. And letting 24,000 seedlings die at $3 per seedling was not in the plan.

So when January came with no rain, she says, “We just said, ‘That’s it—we’re planting.’” Since January 17, Irvine says, she and a crew of interns and volunteers have been struggling to get the groundcover into the earth, which is so hard and dry that they’ve had to drill holes for the plants with a motorized augur.

“That’s 24,000 holes,” she says. “It’s been very slow going. We’ve only gotten about 9,500 plants into the ground, and we’ve been out there every day but Sunday and Martin Luther King Day.” Most recently, she says, she set aside $10,000 so she could water the plantings if necessary with a fire hose and a water tanker.

“If it rains substantially, of course, all bets are off,” Irvine says. “But from what I understand, just to get back to normal we’d have to have a couple of inches a day from now until about May.”

"You can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” Irina Irvine says of the drought. Seen here in green, she gets the troops ready for planting seedlngs in the hard dirt. Photo/Steve Friedman

Posted 2/6/14

Not just a local hero

February 6, 2014

For 40 years, Rep. Henry Waxman has represented a wide swath of Los Angeles’ Westside. But the truth is that no single member of Congress has had a more far-reaching impact on the health and well-being of the entire nation than Waxman.

He championed legislation that led to cleaner air and water not only in L.A. but also in polluted cities across America. He was the driving force behind bills that restricted the use of pesticides and required food manufacturers to put those now-familiar nutrition labels on their products. He made sure that children in lower-income families had access to health insurance. He wrote the law that created the generic drug industry, saving consumers countless millions on their prescriptions.

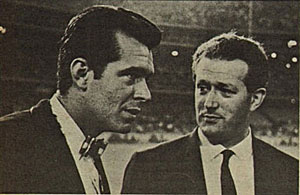

And remember back in the mid-1990s, when the heads of the nation’s tobacco companies were collectively summoned to Washington for a televised hearing, during which they denied that their product was addictive? That landmark session was convened by Waxman, and it represented a turning point in the long and ultimately successful efforts to give the federal government more power to regulate tobacco.

Although Waxman is a proud liberal Democrat, a good number of those bills—and many others—were signed into law by Republican presidents, a testament to his mastery of the legislative process and his ability to build respect and consensus on both sides of the aisle.

With that legacy of accomplishment, it’s no wonder that, in recent days, there’s been an outpouring of praise for my friend and role model, the 20-term congressman. Last week, Waxman, surprised us all when he announced that he’d be retiring at the end of this year. At 74, he explained, it was time to begin the next chapter of his life. I can certainly understand that desire on the part of someone who has devoted his entire adult life to elective office. But I wish it wasn’t so.

Waxman’s departure will leave a huge void in Congress. Among many other things, his has been a powerful voice for the positive role government can play, especially in protecting the public health, whether you’re among the most fortunate of us or those struggling at the lower rungs of the economy. It’s not an exaggeration to say that his legislative work has saved millions of lives. He will surely be remembered as a huge idealist, but one with an unparalleled pragmatic capacity to turn those ideals into reality.

He also has been a great friend to Los Angeles County. In the mid-1990s, for example, when the county was confronting bankruptcy and the collapse of its health care system, Waxman stepped in to help secure the Clinton Administration’s help. In 2008, when federal officials wanted to sell off the Veterans Administration properties in Westwood, where so many deserving men and women have received assistance, Waxman again came to the rescue.

On a personal note, no public servant has taught me more about what it takes to bring about positive change in our society. Through his example, Waxman showed me that it’s not enough to have a vision. You must be willing to stay in the ring despite the long odds you may face. And when you’re knocked down, you get up and keep fighting for what you believe in.

As one of his longtime constituents, I’m grateful for his unmatched advocacy.

He’s going out a champion.

Waxman's tobacco hearings represented a turning point in bringing greater regulation to the industry.

Posted 2/6/14

We loved them yeah yeah yeah

February 6, 2014

Fans mobbed the Hollywood Bowl for tickets to the Beatles' 1964 Los Angeles debut concert. Photo courtesy of The Music Center Archives/ Otto Rothschild Collection

It was 50 years ago this summer that four lads from Liverpool took the stage of the Hollywood Bowl, ushering in Beatlemania, Los Angeles-style.

Before the end of their 30-minute set on August 23, 1964, this much was certain:

A long-running love affair between the Beatles and Los Angeles was underway. Initially it involved mass hysteria, stealthy getaways, partying with local swells and celebrity hobnobbing on the Sunset Strip. Eventually it blossomed into “Breakfast with the Beatles,” a record label romance, a song, an uncomfortable meeting with Elvis in Bel-Air, even a Tower Records commercial.

At the same time, the Bowl itself was experiencing an electrifying new chapter in its fabled history, as a generation of screaming teenagers converged on the place where their parents had thrilled to popular stars like Frank Sinatra and classical music greats like Jascha Heifetz and Vladimir Horowitz.

Suddenly, it was a whole new ballgame.

“I think that night in 1964, that’s the most famous concert in American history, not counting Woodstock,” said Bob Eubanks, then a 26-year-old Los Angeles deejay and owner of two “Cinnamon Cinder” nightclubs, who produced the Beatles show by mortgaging his house for $25,000. “The boys at the Hollywood Bowl told us we couldn’t sell this thing out in one day, that it was physically impossible. Well, we sold it out in 3½ hours—without computers, by the way—and away we went.”

Paul McCartney backstage at the Bowl in '64. Photo courtesy of The Music Center Archives/ Otto Rothschild Collection

Along with thousands of smitten schoolgirls, stars like Lauren Bacall, Debbie Reynolds and Michael Landon turned out for the performance. Gossip queen Louella Parsons had to be relegated to the back benches—“she let us know about that for a long time,” recalled Eubanks, who went on to national fame as host of “The Newlywed Game.”

Ticket prices ranged from $3 to $7. Fans who couldn’t get in climbed trees around the amphitheater as “Twist and Shout,” “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” rocked the Cahuenga Pass. After the final number, a cover of the Little Richard hit “Long Tall Sally,” the band was whisked away in a tiny compact car and was getting off the 101 Freeway at Sunset Boulevard before the audience knew what hit them. “The kids still thought they were there and they ruined two limos out back,” Eubanks said.

From his vantage point as a deejay at KRLA, the city’s top rock ‘n’ roll radio station at the time, Eubanks had known for months that something big was on its way.

“Suddenly, there were these four guys from England who just changed the world musically,” he said. “Our phones just started to ring off the hook…It started the night they did the Ed Sullivan show, quite frankly. When we heard they were coming to America, the country started to really buzz.”

This year, the buzz is back. With the 50th anniversary of the group’s first appearance on the Sullivan show taking place this Sunday, February 9, there’s no shortage of magazine covers and think pieces analyzing the British Invasion. And the Hollywood Bowl, where L.A.’s adventures in Beatlemania began, this week announced that it is marking the occasion with three “The Beatles’ 50th at the Bowl” concerts in August. (Those aren’t the only ‘60s flashbacks in store at the Bowl, by the way; the summer schedule also includes performances of the musical “Hair”—complete with “simulated drug use” and “brief nudity.” Check out the complete Bowl schedule here.)

Fainting girls went with the territory. Photo courtesy of The Music Center Archives/ Otto Rothschild Collection

Dave Stewart (of Eurythmics fame) will be “ringmaster and musical director” for the August 22, 23 and 24 Beatles shows at the Bowl, which will include yet-to-be-announced special guests and a re-creation of their original musical set from 1964.

Eubanks said he’d like to take part in the shows if possible. As the 50th anniversary approaches, he has also reached out to Paul McCartney. In an email reply, read by Eubanks in a telephone interview this week, the former Beatle demurred about his availability on the anniversary date but sent along reminiscences of the “heady days of our early trips to L.A.” and this message to fans:

“It was a fantastic time for us and I still have many memories of the things that we got up to. It was great to play the Hollywood Bowl even though our music was completely drowned out by the screams of our lovely fans.”

The Hollywood Bowl Museum is gearing up for the occasion as well. Carol Merrill-Mirsky, museum and archives director for the museum and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which operates the county-owned Bowl, has commissioned a 3-D model of the Beatles in concert. It will be showcased this summer along with the small cache of Beatles memorabilia—including a copy of Eubanks’ contract for the 1964 concert—that’s on regular display.

Tickets for the 1964 show sold out in 3½ hours. Photo courtesy of The Music Center Archives/ Otto Rothschild Collection

She also has been combing through old pictures from the Music Center archives to put on display—although there are not a lot of images in the collection from that initial concert. She thinks that’s because, aside from Eubanks, few saw the magnitude of what was about to unfold that night.

“He had an instinct that it was going to be huge but nobody else did. Nobody. Certainly the Bowl didn’t, and the fact that we have so few photographs is proof that it was not a big deal. But it was a big deal to the fans—to those teen fans.”

Despite the frenzy among local teens, not everyone was thrilled to see the Fab Four arrive in Los Angeles in 1964. “They wanted to stay at the Ambassador, but the Ambassador didn’t want ‘em,” Eubanks remembered. A house in Bel-Air, complete with “a pool and the whole nine yards,” was lined up instead.

On the night of the concert, a busload of marshals showed up at the Bowl, ready for deployment to “protect the neighbors up in the hills.” Eubanks thought it was a great idea until he realized he was going to be footing the bill.

As a result, he said, he ended up making only about $4,000 on the 1964 concert. But Eubanks, who went on to produce all of the Beatles’ L.A. concerts—two performances at the Hollywood Bowl in 1965 and a 1966 show at Dodger stadium—did “quite well, thank you” on the later gigs.

Eubanks, with Beatles publicist Tony Barrow at Dodger Stadium in 1966, witnessed the band's evolution.

He also had the priceless experience of seeing the band’s three-year evolution—from “wide-eyed and curious” in 1964 to seasoned “road warriors” in 1965 to “very difficult” in 1966.

After the last-ever Los Angeles show in 1966, he remembers arguing with John Lennon in the Dodgers’ dugout after the original getaway car failed to make it out of the stadium.

“We got into it pretty good with John down there because he wanted to get to a party. ‘You’ve gotta get us out of here.’ We went nose to nose. And finally I said, ‘I’ll get you out of here.’ We went upstairs and put them in the back of an ambulance.”

The driver “was nervous as heck. He drove right down through 40,000 people…he hit a speed bump and the radiator fell out of the ambulance.”

Finally, they reached a rendezvous point with an armored car that was intended to complete the trip away from the stadium. But it was mobbed with teenage girls and the Beatles’ escape seemed to be foiled again.

“And all of a sudden, I have no idea where they came from, the Hells Angels showed up,” Eubanks said. “They circled the armored car, the kids backed off, and the Hells Angels led the Beatles from Dodgers Stadium. And that was the last time I saw the Hells Angels or the Beatles.”

Running into the Bowl in 1965. Photo courtesy of The Music Center Archives/ Otto Rothschild Collection

Posted 2/6/14

Trial by fire for Metro’s new top cop

February 6, 2014

Commander Claus is a SWAT veteran with a dramatically different set of new responsibilities at Metro.

Sheriff’s Commander Michael Claus became the new head of security for Metro’s bus and rail system on January 6. He knew the job would be complicated, but he couldn’t have predicted what would happen next.

A week after he started, on the morning of January 13, a fatal stabbing took place on the Red Line. It was the second killing in the history of the line, and the widely-publicized tragedy forced Claus to throw out his playbook.

“If you can imagine taking a big, giant eraser board that has everything laid out nice and neat, and then just take both hands and move everything around? That’s what it was like,” Claus said.

Luckily, his police instincts kicked in.

“When something like this occurs, you have two issues,” Claus said. “One, you have to solve the problem, find out who did it and hopefully have an arrest—which we did. Second, as an administrator you have to look at what we did, whether we could have prevented it and what we can do now to prevent it in the future. You have to wear two hats.”

The first part comes naturally for Claus, 52, who has more than 33 years of experience as a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputy, SWAT team member and SWAT commander. The administrative part is new territory.

“I left my dream job,” Claus said. “When I was a deputy at SWAT, I always said I wanted to be the first person to work on the unit and then go back and command the unit. And I was the first person to do that. Eight months later I get a phone call and the sheriff asked me to come over here and command this bureau. You don’t tell the sheriff ‘no.’ ”

After decades on patrol, Claus now finds himself doing much of his work from behind a desk.

“This is completely different from anything I’m used to,” he said.

One immediate challenge has been managing public perceptions in the wake of the stabbing, which raised safety concerns among many transit riders. Claus said those fears are understandable, but they’re distorted by this isolated event, in part because of how the media covered it. “It’s like a plane crash,” he said. “After a plane crash they tell you it’s the safest transportation mode in the world. But when there’s a murder, the news doesn’t do that.”

According to Sheriff’s Department statistics, “Part 1” crimes, which include homicide, rape, aggravated assaults and theft crimes, are exceedingly rare on Metro’s system. On the Red Line, for example, there were only 3.8 of those crimes per million riders in 2013. Violent crimes are even rarer, with property offenses like the theft of electronic devices accounting for the majority of that number.

Other than a police station parking lot, Metro is one of the worst places to commit a crime. Perpetrators rarely get away because closed-circuit TV cameras are always watching and camera-equipped passengers serve as witnesses, Claus said. The suspect arrested and charged with the Red Line stabbing was identified using footage from train and station cameras.

“If Metro’s system were a city, it would be the safest city in the country,” said Duane Martin, who manages the agency’s work with the Sheriff’s Department. “People tend to focus on occurrences that are out of the ordinary. When something like this happens on Metro, it stands out.”

Still, even one crime is too many for the people charged with protecting the riding public. Claus is already brainstorming improvements. One idea he’s considering is assigning teams of deputies to the same couple of stations or bus stops every day to create a transit version of community policing, enabling the deputies to get familiar with regular patrons—and potential troublemakers. Currently, deputies are generally assigned to regions that they are familiar with and moved around as needs dictate. Claus wants to focus them on smaller beats to give them a proprietary interest in keeping each area safe.

Both Claus and Metro’s Martin are seeking to improve fare enforcement, a major priority for the agency. Currently, deputies are responsible for making sure that people pay their fares and for issuing citations to violators. But Claus believes that sworn deputies’ skills are better used elsewhere.

“From what I’ve seen so far, I think it’s a waste of a resource for a deputy sheriff to check TAP cards,” Claus said. “Deputy sheriffs should be performing law enforcement functions, not revenue functions.” He added that it’s tough to recruit good people because trained police don’t want to spend their days checking cards.

Claus envisions using Metro employees and security assistants to check fares instead, while deputies patrol for safety—a quick call away if a conflict arises. Martin agrees. “When they are on a train and they have both hands checking tickets, they aren’t looking for quality of life issues,” Martin said. With each sworn deputy costing the agency about $210,000 per year and civilian employees costing about a quarter of that amount, “you want to get the best bang for your buck.”

Claus also wants to improve how his team communicates with the public. “We are going to start educating people about how not to be victims,” he said. Part of that involves common sense steps like securing purses and electronic devices. However, in the case of a verbal or physical confrontation, he said, the best course of action is to be a good witness and stay out of the way. “It’s hard for me to say ‘don’t get involved’ because I’m one of those guys that would get involved,” Claus said. But, as a law enforcement officer, he pointed out, “I also carry a gun.”

Suspicious activity, of course, should be reported by dialing 911 or calling the Sheriff’s Department. But there’s a catch. That only works on buses and above-ground light rail; there is currently no cellular or wireless internet service on the subway. There, passengers should look for emergency phones at either end of each rail car and in the stations, or try to find a Sheriff’s deputy or a Metro employee. The agency is in the process of installing wireless service underground, but the effort will not be completed for about a year. “All we have is radio down there,” Martin said. “Having telephone service will be a godsend for us.”

The Sheriff’s Department acts as an independent contractor with Metro, which is paying the department about $83 million for the current fiscal year. The contract expires in June, and Martin expects that the next contract, which must be put through a competitive bidding process, will include new performance standards and different fare enforcement requirements. The current contract started in July, 2009, before TAP cards and gate latching were implemented. Back then, fare enforcement was done mainly by checking individual paper tickets.

Commander Claus hasn’t been on the job long, but he’s adapting quickly to his new position, which also involves delicate political situations he hasn’t faced before.

Because Metro’s territory cuts across many political boundaries, moving resources around can be touchy. “One of the lines may go through one county Supervisor’s district and one goes through another. They might ask ‘why are you taking resources from my district?’”

On top of that, there’s inherent friction between law enforcement’s duty to investigate crimes and Metro’s mission to reliably transport millions of people from place to place on time. Stopping rail lines for lengthy investigations can be a complex undertaking. “You have to find that happy medium,” Claus said.

It all adds up to a brave new world for a man who decided to become a police officer at age 5 while watching cop shows on television. Like any good administrator, his first task will be to take stock of what he already has.

“I love a challenge,” Claus said. “It’s like taking over a factory that makes cars. First you are going to learn how to make the car, and then you’re going to see if you can do anything better.”

Posted 2/6/14

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information