Top Story: Transportation

Valley-Westside express bus is a go

October 1, 2014

Taking advantage of those brand-new 405 carpool lanes, Metro later this year will launch an express bus through the Sepulveda Pass, offering transit riders on both sides of the hill a speedier way through one of L.A.’s gnarliest commuting challenges.

On December 15, Line 788 will begin offering express nonstop service from UCLA in Westwood to the Orange Line in the San Fernando Valley. It then will continue north on Van Nuys Boulevard, stopping at major intersections on its way to Panorama City. Because it will connect to the Orange Line rapid transit busway, the line will give people in places like North Hollywood, Woodland Hills and Chatsworth a faster path to the Westside.

According to Jon Hillmer, Metro’s executive officer in charge of bus service planning and scheduling, the new line is projected to save a lot of time for commuters now riding other lines.

“We’re being very conservative, but from end to end we are looking at 20 minute time savings in each direction,” he said.

Service through the Sepulveda Pass currently is offered via Line 761, but the buses are infamously slow, having to navigate traffic and wait for stoplights along Sepulveda Boulevard. It currently takes more than an hour to get from one side of the hill to the other in normal traffic.

Initially, express buses will depart every 20 minutes on weekdays during peak traffic periods—from 5:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. to 7 p.m. Hillmer believes the line will draw a lot of riders in short order. If that’s the case, the frequency of buses will be increased and more daytime hours will be added. “If this gets to be very popular and we have overloads, we will add service very quickly,” Hillmer said.

The line could prove particularly useful for UCLA students, who qualify for reduced fares from Metro. The university also subsidizes at least 50% of transit costs with six local agencies for students and employees.

Using the 405 Project’s carpool lanes for buses was first suggested last fall at two Local Service Councils—appointed bodies that give Metro a regional perspective during the annual process of adjusting bus routes.

“The public was very supportive of the idea,” Hillmer said. “It was virtually unanimous that there was a need for nonstop service between the Valley and the Westside.”

Then Metro’s Board of Directors in May requested that the agency prepare the studies and tests needed to launch the service. One potential roadblock was whether buses could maintain highway speeds while climbing the steep hill that separates the Valley and the Westside. Fortunately, Hillmer said, Metro’s 45-foot coaches—which are built with lightweight composite sides—proved able to maintain speeds of at least 55 miles per hour in each direction.

Further down the road, Metro plans to extend the express line south to the Sepulveda station of the Expo Line when the final phase of the light rail project opens in January, 2016. That will give people another option to reach destinations such as Santa Monica without having to deal with driving, not to mention the city’s notoriously difficult parking.

Line 788 may soon get a catchier name. Today, at Metro’s Executive Management Committee meeting, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and his Metro board colleagues Paul Krekorian and Pam O’Connor introduced a motion to begin promoting the line as the “Valley-Westside Express.” That proposal will go before the agency’s full Board of Directors next Thursday, September 25.

Whatever it’s called, Hillmer said the line will give residents of a broad area a new way to get from the Valley to the Westside—and vice versa.

“This will be a very attractive service because it’s fast and easy to use,” Hillmer said. “Because it interfaces easily with the Orange Line, people who have destinations on either side of the 405 will have faster access over the hill.”

The bus line will roll though the Sepulvenda Pass via the new carpool lanes. Photo/Metro's The Source

Posted 9/18/14

Give ‘em three—or face a fine

August 27, 2014

As a frequent bicycle commuter in Los Angeles, Nathan Lucero is used to blaring car horns and close encounters with vehicles whizzing by.

“I’ve had plenty of close calls. I actually got honked at this morning….they buzzed me on the left side,” says the 32-year-old industrial designer, who lives in Eagle Rock and rides his bike a couple of times a week to his job in the South Park area of downtown L.A. “Then I got buzzed by a little Mini two minutes later.”

Lucero, who has taken to wearing a helmet camera to capture such encounters, says he is thinking about editing his footage into an educational video.

His timing couldn’t be better. On September 16, the so-called “Three Feet for Safety Act” goes into effect in California, specifying for the first time a state standard for safely passing bicycles.

As cycling becomes more popular in Los Angeles and around the state, sharing the streets has never been more important. The new law, championed by state Assemblyman Steven Bradford of Gardena and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown last year, is part of a broader movement, including the “Give Me 3″ campaign launched in the Los Angeles in 2010, and is intended to literally spell out the rules of the road for the first time.

The measure requires motorists to pass bicyclists by at least three feet, or, if that’s not possible, to slow down until there is an opportunity to pass safely. Violators face a $35 fine, which goes up to $220 if a driver passing unsafely collides with and injures a bicyclist.

Lucero thinks that could make a big difference on streets that can still be pretty mean for those traveling on two wheels instead of four.

“Drivers are going to start getting tickets. And drivers are going to start to be accountable for the things that they do,” he says. “I don’t think you need a lot of enforcement. You just need a couple of people getting tickets and they talk to their friends or they complain on Facebook.”

For Officer Troy Williams of the LAPD’s Valley Traffic Division, the new law presents a teachable moment. He’s already been spreading the word within the department, at Neighborhood Watch meetings and at other public gatherings for months.

While some targeted enforcement is in the works, Williams thinks it’s unlikely that officers will be handing out huge numbers of citations unless they happen to witness violations happening right in front of them.

But the new law could be important in establishing who was at fault after a car vs. bike collision, Williams says: “It’s a new tool in the arsenal.”

In any case, law enforcement’s initial emphasis will be on building public awareness.

“You’re not going to see us on September 16th writing tickets for not giving that three-foot buffer or for not slowing down and passing at a reduced speed,” says Leland Tang, a public information officer with the California Highway Patrol. “We’ll be trying to educate people. So yeah, we will be pulling people over and educating them. Just know that it’s a very lengthy process. It’s going to take a lot of time and a lot of effort to change the culture and to really educate the public that bicycles are vehicles. Bicycles have every right to be on the road, just like any car or motorcycle.”

Tang says he believes most motorists will come to accept and understand the law, particularly if they see bicyclists being penalized for violations as well. (Common complaints involve cyclists running stop signs and red lights, or riding the wrong way in traffic, he says.)

“We’re going to be making sure that bicyclists follow the rules of the road as well,” Tang says.

The Automobile Club of Southern California has been working with the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition and the California Bicycle Coalition to publicize the three-foot law. The campaign includes splashy bumper stickers and window clings, designed by Wire Media, featuring the slogan:

“I give 3 feet. It’s the law.”

AAA is including news about the law in its Westways magazine, and also is organizing a six-day campaign, starting September 10, in which all of its tow truck drivers will hand out information cards on the three-foot zone to people who call in for service.

“Definitely the time has come for California to have a safe passing law,” says Marianne Kim of the Automobile Club, pointing out that many states now have such laws on the books. “It’s an important reminder that we share the road with everyone.”

And that’s more than just a matter of courtesy, bike advocates say.

A recent report by the League of American Bicyclists analyzed a year of crashes in which bicyclists were killed, and found that 40% of the 628 victims had been hit from behind.

That suggests that driver awareness of buffer zone laws could make a difference in averting such crashes in the future, says Colin Bogart, programs director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition.

“Just about any cyclist who’s ever felt the uncomfortable rush of a driver passing far too closely will be very happy when this law goes into effect,” Bogart says. “I do think it could result in a reduction of collisions.”

Posted 8/25/14

Tough audit sparks reforms

July 17, 2014

A sheriff's deputy keeps an eye on goings-on at a Blue Line platform last fall. Photo/Los Angeles Times

A hard-hitting new audit says the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department has failed to live up to its multimillion dollar contract to police the Metro system, while the transit agency itself has done a poor job of monitoring the sheriff’s performance.

The audit was commissioned by Metro’s Board of Directors last year and performed by the firm Bazilio Cobb Associates, with a team including members of the Bratton Group, LLC. The May 27 report faulted the sheriff on a number of fronts, including lack of a community-policing plan for the nation’s third-largest bus and rail system, perennial staff vacancies, tardy responses to citizen complaints and inadequate records to support its billings.

Overall, the audit determined that both the Sheriff’s Department and Metro had significant improvements to make.

“We found that Metro needs to substantially strengthen and enhance its oversight of LASD contract performance,” it said. “We found LASD has not met many of the targets for performance metrics, including crime reduction, continuity of staff, and fare enforcement saturation and activity rates.”

The audit was presented to Metro’s System Safety and Operations Committee on Thursday. CEO Art Leahy told the panel that new management at the sheriff’s department now has “an intense focus on delivering the goods here. There’s no finger-pointing, there’s no excuses. They can do better and Metro can do better.”

Sheriff’s Cmdr. Michael Claus, while disagreeing with a few of the report’s conclusions, said most of its 50 findings were on target.

“The bottom line is: we didn’t do what we should have done,” Claus said in an interview. “No one likes to be told they’re not doing a good job, but they were right in a lot of areas.”

Claus, who became Metro’s head of security in January, said reforms already are underway. Those include upgrading the Transit Services Bureau into a full-fledged sheriff’s division with its own chief, to whom Claus now reports. That move, effective July 1, will give structure to the team and enable it to advocate more effectively for staff resources, Claus said. It also may be a morale-booster for deputies assigned to the transit beat, which the audit said has been considered undesirable or even punitive by some within the department.

“By making it its own division, probably 20 people have removed their transfer requests,” Claus said.

The audit comes as the sheriff’s Metro contract—by far the department’s largest—is up for renewal. The new contract will likely be worth more than $400 million over five years, the report said. The department currently is working under a $42 million six-month contract extension that expires on Dec. 31.

The audit covered five years beginning July 1, 2009 and found lots of room for improvement. Among its findings:

- Critical information—such as up-to-date blueprints and maps of station layouts—needed in the event of an attack on Metro’s transit system has not been shared with key tactical response units within the sheriff’s department. (Claus, a former SWAT officer and commander, said an effort to provide up-to-date, digitized information is underway, but insisted that the sheriff’s units in question already are familiar with Metro facilities.)

- The transit security operation has operated with high levels of vacancies and too often sends in substitute staff without the necessary transit expertise.

- The department has double-billed for some supervisors’ time; billed Metro at the full rate even when managerial, supervisorial and support positions went vacant; failed to provide enough backup documentation of time being worked; and in fiscal 2011 submitted bills of $59,368 above the maximum amount allowed under the contract.

- Customer complaints against deputies often are not processed on time, and deputies with multiple complaints against them usually aren’t routed into the department’s “performance mentoring program.” (Claus said a backlog stretching to 2010 has now been eliminated.)

- Mobile phone validators used by deputies to check patrons’ TAP cards are technologically inadequate and can’t be used for basic crime-fighting tasks, such as looking for outstanding warrants when people are stopped for fare checks. Better fare-validation devices are being developed, the audit said, but other issues involving checking TAP cards remain unresolved—notably the question of whether that duty should be handled primarily by Metro’s own security staff rather than sworn deputies.

- Crime reporting and response time statistics are not being appropriately reported. (The department has switched, as recommended, to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting standards, Claus said. He said the department disagrees, however, with a recommended change in reporting response times that would start the clock running when a Metro operator receives a call—not when it reaches the sheriff’s department.)

The audit also said the sheriff’s transit security team was not engaged enough in making quality of life improvements in Metro facilities.

But, according to the sheriff’s department, that finding overlooks a notable recent success story.

“Deputies have made tremendous strides in cleaning up Union Station; examining and solving delicate homeless rights issues, solving quality of life issues, making the area a cleaner, hazard-free experience for patrons, etc.,” according to the official response to the audit from interim Sheriff John Scott. “More is to be done, but to say that great strides have not been obtained would simply not be reflective of the current status.”

As for Metro, the audit found that the agency has failed to set forth adequate contractual requirements for the sheriff’s department, and has been lax about keeping tabs on the requirements that are in place.

In a response to the audit, Duane Martin, the agency’s deputy executive officer for project management, wrote that his department is asking for more staff to provide better contract oversight. He said Metro also will seek to modify its existing contract to enable it to seek damages if the sheriff doesn’t live up to specified performance targets—including crime reduction and continuity of staffing—and will write that into the next contract as well.

Beyond the audit, Metro CEO Leahy said he also has ordered a peer review of his agency’s security services by the American Public Transportation Association. Those findings will be examined, along with the audit, by Metro’s board this fall.

Posted 7/17/14

Metro’s park ‘n’ gripe problem

June 25, 2014

Angelenos cite lots of reasons for sticking with their cars rather than taking public transportation, but here’s one excuse that even Metro acknowledges can be valid:

Not being able to find a parking space at the station.

A new report by the transit agency found a dramatic parking space shortfall at the two Red Line subway stations in the San Fernando Valley, where customer demand is more than triple the supply. That means that thousands of commuters looking to ride the subway to Hollywood and downtown L.A. may be forced to stick with the congested freeways instead.

“If I’m already in my car and the lot is full, I don’t have any choice—I stay in my car and drive,” says Calvin Hollis, Metro’s planning manager in charge of parking. “I think that’s what’s happening.”

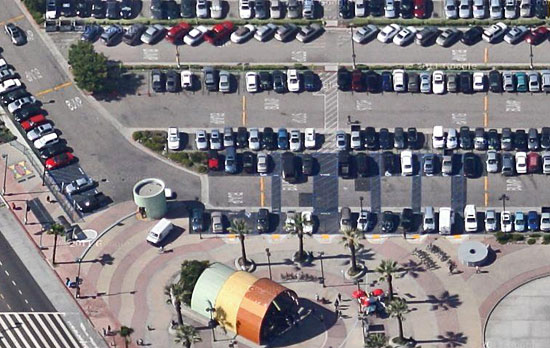

Overall, parking capacity at Metro’s rail stations and its Orange Line rapid transit busway is a mixed bag, the report found. The 11 busiest lots include the two at Red Line stations in the Valley, five on the Gold Line and three on the Blue Line—all of which are operating at 85% capacity or greater. At the other end of the spectrum are facilities like the lot at the Orange Line’s Sepulveda station, which is operating at only 8% of capacity.

The report measured “unconstrained demand,” transportation parlance for the number of cars that would park if there was unlimited space and no restrictions, as determined by a complex formula including socioeconomic data and passenger surveys.

At the North Hollywood station, those numbers add up to a whole lot of aggravation for drivers who might prefer to transfer to the subway, with unconstrained demand of 3,014 vehicles on an average weekday but only 951 available spots. The mathematics of parking also are bad at Universal City, where the demand is for 2,124 spaces per weekday with just 565 spots available, plus 281 more at adjacent county and state-owned lots.

There are plans to add 500 spaces in North Hollywood over the next two years, but that still won’t come close to meeting the demand. At Universal City, a lack of Metro-owned property means that few easy options are available in the short term. Existing lots can be reconfigured to squeeze in a few more slots, but that’s about it.

Hollis says Metro’s Board of Directors needs to decide whether to take more aggressive steps, which could include building parking structures or acquiring more land. Another option is working with private developers on projects that provide transit parking in addition to residential and commercial spaces. One such agreement was struck in 2007, but the real estate crash of 2008 forced the developer to back out. Now that the market has bounced back, Hollis says, Metro is preparing to revisit the option of joint development by issuing a new request for proposals.

The parking capacity report comes in response to a December motion by L.A. City Councilmember Paul Krekorian, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and Mayor Eric Garcetti. The motion directed the agency to look at the frustrating situation at the Red Line stations, which serve as a transit gateway to Hollywood and downtown L.A for millions who live in the San Fernando Valley and places further north.

Metro also is reviewing the dynamics of parking throughout its entire rail system, which is expanding to more communities with projects like Expo Line Phase 2, the Gold Line Foothill Extension and Crenshaw/LAX. The first phase of the Expo Line, which extends from downtown L.A. to Culver City, is already feeling the crunch.

“The Culver City lot is at capacity, so I think we are going to have the same situation that we have at North Hollywood,” Hollis says.

Aside from availability, the agency also may need to revisit its policy on selling reserved spaces at busy lots, Hollis says. While the practice generates some revenue that can be used to build more spaces, it also decreases the number of cars that can park during rush hour. “We are reserving spaces that don’t get used during the peak time and they sit there empty,” Hollis says.

Hollis will present his findings to the agency’s Board of Directors in July. He’s also recruiting Metro’s first director of parking—someone with substantial experience managing large systems.

Metro currently has more than 10,000 spaces, but now is in the process of acquiring 42 state-owned lots with a total of 12,000 spaces. (None of which, unfortunately, will be going toward alleviating the shortage at the two Valley subway stations.) Additional new spaces will be coming into the system as Metro’s rail network expands in the years to come. It all adds up to a lot of territory, and issues, for a new parking czar to oversee.

“We have to realize we are in the parking business,” Hollis says. “We’re going to have about 30,000 parking spaces. It’s time to get serious about it.”

It's also tough to find a parking space at the Expo Line's Culver City station. Photo/Streetsblog LA

Posted 6/25/14

The whammy on Wilshire

June 12, 2014

As the 405 Project starts to move out of the limelight as L.A.’s most groused-about long-running transportation project, attention is shifting to a new construction hot zone: Wilshire Boulevard.

With a litany of high-visibility public and private projects in the works or on the horizon, the legendary boulevard is gearing up for a years-long building boom, particularly in the Miracle Mile.

“Seriously, if it’s not one thing, it’s another,” said Ginny Brideau, a consultant with The Robert Group who is handling community outreach for one of the projects, a new lane dedicated to buses at rush hour and available to all drivers at other times.

As part of that project, crews already are building special lanes and resurfacing Wilshire from Western Avenue to San Vicente Boulevard—work that entails closing lanes, detouring sidewalk traffic and putting up temporary no-parking signs.

Later this month, things start heating up miles to the west, as work begins on another bus rapid transit segment near the V.A. in West Los Angeles—close to where the 405 Project has been a high-profile challenge for nearly five years. Construction of the short (less than ½ mile long) bus lane on Wilshire between Federal Avenue and Bonsall Avenue will bring lane closures for the next seven months. That includes a period in which traffic will be detoured away from ramps connecting Wilshire to the Bonsall underpass. (Details are here.)

The Wilshire bus project is intended to create a faster-moving 12.5-mile corridor for rush hour riders between MacArthur Park and the Santa Monica border, and to improve traffic for everyone by tempting more people to ditch their cars and hop aboard public transit.

But it’s just the first leg of what promises to be an epic journey on Wilshire. Here’s a brief taste of what’s happening now, or coming down the road soon:

- The project to extend the Purple Line subway from Western to La Cienega Boulevard is currently busy with utility relocation, including after-hours jackhammering and saw-cutting. The action is expected to intensify in the months ahead when demolition begins on the first of 17 buildings set to come down to create staging areas for the project. Actual subway construction, including pile-drilling and station excavation, will start next year, according to a timetable presented at a recent community meeting. A more immediate impact: next week’s closure and relocation of Metro’s Wilshire/LaBrea customer service center.

- At the same time, private developers have started work on the Desmond on Wilshire, a new 7-story apartment structure in the Miracle Mile that’s expected to be finished by next summer.

- Then there’s the new Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences museum, designed by Renzo Piano, to be built on the old May Co. site at Wilshire and Fairfax Avenue and heading for a 2017 debut.

- Right next door, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is developing plans of its own for a new building by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor to open in 2023, replacing several aging buildings on the museum campus.

In the scheme of things, the Wilshire bus rapid transit project is expected to wrap up relatively quickly, by next year.

“I’m thrilled that it’s going in,” said James O’Sullivan, president of the Miracle Mile Residential Association. “It’s made a mess out of Wilshire, and 8th Street has become a jungle at times. But it’s short term.”

There’s a much longer road ahead for the subway extension.

“Our issue all along has simply been: we don’t understand how we can do nine years of this, 24/7,” O’Sullivan said. “We know it’s coming. We know it’s going to go in. We have lots of questions.”

Complicating matters is the sometimes confusing welter of agencies with a piece of the action: the county is building the bus lane from Federal to Bonsall, the city is constructing the rest of the bus rapid transit project, Metro is in charge of building the subway and is funding much of the bus lane work, utility companies are out in force moving lines in support of a variety of projects, and the Los Angeles Police Commission is responsible for canvassing residents and businesses when a project needs an exemption from work hours requirements under the city’s noise ordinance.

In the midst of all that, consultant Brideau said she understands how people feel when they experience problems: “You don’t care who it is, you just want it to stop.”

She recently came to the rescue of a toy store owner who arrived one day to find that a contractor had unceremoniously installed a portable restroom right in front of her business. Brideau also has been known to remove no-parking signs left up too long after bus lane work has concluded.

Calls to the bus rapid transit project’s hotline—(213) 922-2500—are promptly returned, Brideau said, and so are messages left on its Facebook page.

As for the subway, project director Dennis Mori acknowledges there’s a lot going on, but said the results—new transportation and cultural facilities that will provide a broad public benefit—will be worth it in the end.

“We look forward to the opportunity of integrating our plans and construction activity with the other projects,” Mori said. While there’s lots of coordination ahead, he said, the agency has been there before on other successful endeavors.

“We’ve had those experiences in the past,” he said, pointing to collaborative work between Metro’s Red Line subway team and the group building the Hollywood & Highland center. “We had very busy schedules and both parties worked very closely together.”

Posted 6/11/14

Locking in fares on the Orange Line

May 8, 2014

Fare gates—they may not be just for trains anymore.

When Metro began latching the turnstiles to L.A.’s subways last year, it marked the beginning of the end for the decades-old honor system that enabled many to ride for free. Since then, gate latching has spread rapidly. By the end of May, all rail stations with turnstiles will require a valid TAP card for entry.

Now similar barriers may be coming to the Orange Line busway, which provides rail-like service in bus-only lanes.

A Metro report released Monday said it would be possible to gate all 18 stations of the San Fernando Valley line. Metro’s Board of Directors later this month will decide whether to install gates at an estimated cost of $24.6 million, or go with another option, such as rearranging non-latched card readers—known as “stand-alone validators”—to encourage more people to use their TAP payment cards.

The report recommends a more detailed engineering analysis on installing gates while also testing the stand-alone validator plan at two stations. The non-gating option is cheaper initially and quicker to implement, but it would still rely on the honor system and enforcement by the Sheriff’s Department, said David Sutton, who heads up the gate latching project for Metro.

“Gating is more compulsory,” Sutton said. “It’s going to stop you if you don’t tap. A stand-alone validator is not going to stop you.”

The effectiveness of simply rearranging the TAP card validators is unknown. The option is currently being tested at light rail stations but “the jury is still out,” Sutton said.

If the agency decides to go the gating route, most Orange Line stations will pose no major logistical barriers. However, because the Warner Center station is situated on a public sidewalk, the agency would need to purchase land from the City of L.A. to create space for gates. And, at the heavily-used North Hollywood Station, twice as many gates will be needed to ensure that passengers can get in and out quickly and safely. The entire process, from planning to construction, could take two years or more, Sutton said.

For gating on the Orange Line to be effective, additional fencing must be installed. The current fencing along the backs of station platforms is only 3½ -feet high. It would need to be modified or replaced with 5-foot-high fencing to keep out all but the most dedicated scofflaws.

The move toward gating the Orange Line started in January, after Sheriff’s reports showed that up to 22% of riders were not paying their way. Metro’s Board of Directors, acting on a motion by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and L.A. City Councilmember Paul Krekorian, directed the agency to develop options to fix the problem.

As plans move forward, Sheriff’s Commander Michael Claus—Metro’s head of security—has already ramped up enforcement. By February 11, the fare evasion rate had come down to 7%. And, to bolster his team’s efforts, Claus released a 30-second video that is being broadcast on the buses via on-board televisions. The clip shows riders how to load and use their payment cards—and what the consequences will be if they don’t. Citations for single offenses are usually $75, the current cost of an unlimited 30-day pass.

The estimated $24.6 million cost of gating the Orange Line could be offset by increased revenues. Last fall, Metro estimated it would recover an additional $6 million per year in fares from latching the Red Line alone. Still, according to agency spokesperson Paul Gonzales, installing gates may prove too costly at some locations.

“Some stations may take 10 or 15 years to pay off,” Gonzales said. “Is that worth it? That’s something the Board will have to decide.”

The Orange Line decision comes as the agency faces the possibility of fares going up—always a contentious proposition. Still, even if fares increase, the riding public may be able to take some solace in the fact that there will be fewer freeloaders on the system.

“There’s a basic element of fairness,” Gonzales said. “People think, ‘Why should I pay and other people not pay?’ ”

The decision on the Orange Line goes to the System Safety and Operations committee meeting next week before heading to the full Board for consideration on May 22.

Posted 5/9/14

Love and hate in the express lane

April 24, 2014

When it was time for the public to finally be heard on Los Angeles’ new freeway toll lanes, Metro got an earful.

“I love the Metro Express Lanes!!!!! We should have them throughout the city.”

“These fast track lanes have turned into nothing but Lexus Lanes.”

“Express Lanes are the best thing ever to happen to Los Angeles freeways.”

“The Express Lane program is an absolute joke.”

“Please Please Please…expand the express lanes!!!!!!

“ADMIT IT—IT’S A FAILURE!!!!

Metro had asked for the public’s take in March as part of a broad analysis to help the agency’s board of directors determine whether the “high occupancy toll lanes” on two of Los Angeles’ busiest freeways—the 110 and 10—should be made permanent. And on Thursday, the directors gave a unanimous thumbs-up to extending the experiment, despite the deeply divided motoring public reflected in the more than 700 emails the agency received.

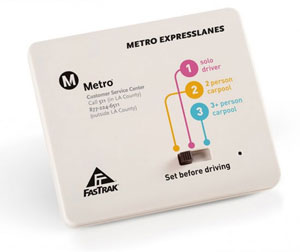

The federally-funded program lets solo drivers, who pay a toll, share lanes with carpoolers, who can continue to drive in them for free, with one important and controversial caveat: everyone must have an electronic device called a transponder to use the “ExpressLanes.” That requires putting $40 into a “pre-paid” toll account, unless a person’s income qualifies him or her for assistance.

Stephanie Wiggins, Metro’s executive in charge of the toll lanes, presented the analysis to the board on Thursday. She said in an interview that she’s “never, never, never” had a job that has attracted so much public heat. “People really love them,” Wiggins said of the new lanes, “or they really hate them. There’s no in-between.” By overwhelming majorities, according to a Metro survey, those who obtained transponders are happy and those who didn’t are not.

Metro director Mike Bonin, who also is a member of the Los Angeles City Council, lauded the pilot program but acknowledged, like others on the board, that it is still a work in progress. “We’re in the breaking eggshells phase of making an omelet,” he said.

It’s not surprising, of course, that the dramatic changes would generate consternation and confusion among motorists who for decades have been freely using the carpool lanes—for 39 years on the 10, east of downtown Los Angeles, and 15 years on the 110, which slices through the heart of the city.

Statistical measures compiled by federal transportation officials in advance of the board’s vote have done little to settle the debate. They can be used by either side to make a glass-half-full/half-empty argument.

The pilot program was intended to improve traffic flow in both the toll and “general purpose,” or free, lanes, while also encouraging the use of transit alternatives, such as the Silver Line buses that travel along the toll lanes. So far, bus ridership has jumped but traffic times are not much different than before the experiment, according to a recent analysis by an independent firm hired by the Federal Highway Administration. Some drive times are slightly faster since the tolls went into effect, while others are slower, depending on the specific hours studied during peak morning and afternoon traffic.

Wiggins acknowledged that “the numbers, on their face, look marginal.” But she said there’s a clear bright spot, too: Solo drivers who’ve moved from the free lanes into the toll lanes have saved more than 17 minutes on some of their drives. And for those who haven’t changed their behaviors and remain in the free lane, they’re not really any worse off than they were before, she said. “And that can be perceived as a positive.”

What’s more, Wiggins noted that the $18 million in net toll revenues generated since the pilot began has far exceeded early projections. That means more money can be reinvested in transit improvements and inducements along the freeway corridors and that no public subsidies will be necessary in the future because the project is raising enough money to be self-sustaining.

As of February, some 260,000 transponders have been issued by Metro, well above the 100,000 that had been set as an initial goal—a fact that prompted board member and L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to remark: “People are voting with their cars.”

Wiggins also reported to the board that, in the future, Metro will work even more closely with the California Highway Patrol to crack down on scofflaws who drive in the lanes without transponders and to ticket solo drivers who cheat the system by setting their transponders to get a free ride by claiming multiple people are in the vehicle.

One of the most controversial elements of the toll lanes project had been the initial imposition of a $3 monthly “maintenance fee” on people who purchased transponders but who used the toll lanes fewer than 4 times a month. The fee was intended to recoup a charge levied for each transponder on Metro by the toll lane’s private operator.

To legions of travelers, it seemed unfair that anyone should be charged for not using something. To encourage drivers to participate in the toll lanes experiment, the Metro board last year waived the fee for Los Angeles County residents, who represent 86% of account holders, according to Wiggins.

On Thursday, the Metro board attacked the issue again, this time voting 8-3 in favor of a motion by director and L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina to impose a $1 monthly fee on everyone with a transponder, no matter how often they use the toll lanes. In this way, she argued, Metro will no longer be underwriting the fee and will have some $2 million more annually to reinvest in the system and in transportation benefits in communities along the 10 and 110 freeways.

Now that the toll lanes are becoming a permanent part of Los Angeles’ famous (infamous?) car-centric landscape, Wiggins said it’s crucial that Metro do a better job of communicating the value of the program to motorists.

A top priority, she said, will be to educate the public on how transportation is funded.

“We didn’t do ourselves any favors,” she said, “by naming them freeways because we know freeways aren’t free.”

Posted 4/24/14

A quicker ride over the hill

March 27, 2014

For the first time in two decades, Metro buses could be running on the 405 through the Sepulveda Pass.

When the $1 billion-plus 405 Project wraps up later this year, its new carpool lane will be the star attraction—and maybe not just for cars.

Metro is considering running a new express bus between the San Fernando Valley and the Westside, taking advantage of the new lane. It would be the first time in two decades that Metro buses have driven the 405 Freeway through the Sepulveda Pass.

The buses would offer a nonstop ride to UCLA and Westwood from Victory Boulevard and the Orange Line. They would also make stops along Van Nuys Boulevard to Nordhoff Street as far north as Panorama City.

Funding still must be identified, but, acting on a motion by Supervisor and Metro Director Zev Yaroslavsky, the agency’s board today directed staff to get moving on the studies, tests and analyses that would be required to launch the proposed new Line 588.

That includes looking at one potential major concern: whether the agency’s buses have the horsepower to maintain high speeds uphill in the fast lane. “The last thing anyone wants is to slow down traffic,” said Jon Hillmer, Metro’s director of service councils.

Express service in the carpool lanes was first suggested last fall by two Local Service Councils—appointed bodies that provide Metro with a regional perspective during the annual process of adjusting bus routes.

Metro’s staff then looked into the proposal, and the line has been taking shape ever since. Earlier this month, the Westside/Central and San Fernando Valley councils held public hearings on service changes and both recommended adding the express service, Hillmer said.

The public was supportive, too, with about 20 people speaking in favor of Line 588 at the Valley meeting.

“That usually doesn’t happen unless we are cancelling bus lines,” Hillmer said. “There is very broad support for this express bus.”

When Phase 2 of the Expo Line opens in 2016, the bus line would have another important connection; it would extend south to meet the light rail line, creating a new pathway to Santa Monica and, heading in the other direction, to downtown L.A.

Before any of that can happen, however, the bus line must be funded. Even after fares are collected, it will take at least $1.65 million to operate it—something the board could authorize as soon as April, when all of the proposed service changes come before it.

In the meantime, for Metro’s operations staff, the approval of Yaroslavsky’s motion means that Line 588 can be further studied and fine-tuned.

Because of increasing congestion, Metro’s buses haven’t taken the 405 freeway through the Sepulveda Pass for 20 years, Hillmer said. Metro Line 761 currently goes through the pass, but it travels on Sepulveda Boulevard, making several stops. (The Los Angeles Department of Transportation does have a bus that runs on the freeway, however—the Commuter Express Line 574, from Encino to LAX.)

Better transit connections between the Valley and the Westside have been on L.A.’s wish list for years. In 2008, voters approved $1 billion for a much larger undertaking that could include tunneling and rail, but that project is on hold as Metro seeks additional funding and project acceleration by partnering with private companies. In the meantime, Line 588 could start service as soon as the 405 lanes open this summer, Hillmer said.

Initially, the bus would be limited to weekday rush hours. But if enough people ride, Hillmer said, it could be expanded to include weekend service—opening a path to new destinations for entertainment, food and shopping for residents on both sides of the hill.

“They are huge economic engines,” Hillmer said of the Valley and Westside. “This opens up all kinds of wonderful opportunities.”

Posted 3/27/14

Fare hike with a freebie

March 19, 2014

As Metro considers changing its fare structure, proposed price increases have captured attention—and generated controversy—as a March 29 public hearing approaches.

But embedded in the plans under consideration is an element that promises to be a bargain for some riders: free transfers.

Metro estimates that half of its customers transfer at least once during their bus and rail trips. Under the current fare structure, individual ticket-buyers must pay an initial fare to ride and then pay again every time they change lines. For those paying the full base fare, that means choosing to pay $1.50 for each leg of their journey, or purchasing a day pass currently priced at $5.

Under the fare restructuring proposals now under consideration by Metro’s Board of Directors, passengers would pay once to board and then would be able to transfer for free within the system as frequently as they wish for 90 minutes. It’s a way of addressing the growth of a system in which bus and rail transfers are increasingly essential to getting around—and Metro is calculating that giving away transfers will eventually benefit the bottom line by enticing more people to try, and stay with, public transit.

Those customers will, however, be paying more to board in the first place if the plan goes through. And those purchasing Metro passes would, in many cases, be hit with even sharper price increases than single-trip buyers.

If Metro’s board approves the proposed changes at its May 22 meeting, the cost of a regular Metro base fare would go from $1.50 to $1.75 starting in September, rising to $2 in fiscal 2018 and to $2.25 in fiscal 2021. Day passes would go from $5 now to $7 in September, $8 in 2018 and $9 in 2021. Other passes, including discounted cards for seniors, students and the disabled, would go up as well. Details are here.

A second proposal under consideration would also raise fare and pass prices, but would include off-peak and peak pricing options to give riders a break if they don’t travel at rush hour.

A major critic of the fare hike plan is the Bus Riders Union, which contends that the proposed fare hike would hurt the poor and violate the civil rights of minorities. Since 1995, Metro has raised fares three times, with the base fare increasing 25 cents to its current $1.50 in 2010, although seniors, students and the disabled were exempted from that increase.

On a late morning this week at the 7th Street/Metro station in downtown L.A., several commuters said they view the proposed fare hikes as a reasonable trade-off for free transfers. But others said they’d rather see different kinds of improvements.

For example, Ural Garrett, a freelance writer and photographer, said that in addition to free transfers, the agency should offer discounted fares for round trips.

Bus security is a big issue for Chigo Ikeme, a 19-year-old student at the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising who makes multiple transfers to get to her job at the Citadel Outlets. She said she would willingly pay more if the funds went directly to boosting security on buses—but otherwise is against any fare increases.

“I feel that they shouldn’t raise the fares,” she said. “Especially for a student, it’s hard to have to pay extra.”

Ikeme and others said they’d like to see Metro’s free transfer program expanded to allow them free passage on buses run by other local transit lines. People who buy Metro’s $85-a-month EZ Pass can do that now, and under the fare restructuring plan, all regular monthly passes would be merged into the program by 2018. By then, the monthly price would be $120—but daily, weekly and discounted passes for students, seniors and the disabled would not be included.

Nevertheless, Reagan Cook, who’s studying for his master’s degree in international relations at USC, said he considers Metro a good deal.

“I come from Toronto, Canada, and I still think the Metro service is incredibly cheap in L.A., relatively speaking,” Cook said. “I understand that they have to increase it eventually.”

Metro officials say the increases are needed to help it offset an operating deficit that will be $36 million by 2016 and is projected to grow in a decade to $225 million. And they add that Metro fares remain a bargain compared to those in place elsewhere, with San Francisco Muni customers paying $2 a ride, New York subway passengers $2.50 and Chicagoans $2 for buses and $2.25 for trains. In addition, all of those agencies allow free transfers, according to Metro spokesman Rick Jager.

“We have absolutely the lowest fares in the country,” Jager said. “If we don’t do something now…we’re looking at huge deficits in coming years.”

Jager said it’s also a chance to give more bang for the buck to cash customers, who pay $1.50 per trip compared to about 70 cents for pass-holders, who enjoy the discount that comes with buying their transit trips in bulk, so to speak.

Cash customers, Jager said, “are really putting more money into the fare-box than the pass-holder…We want to equalize the system to try to be fair to all of our riders.”

In any case, Metro riders are getting a heavily subsidized ride—and will likely continue to do so.

In a report to Metro’s board in January, the agency’s staff said that its “fare box recovery ratio”—the portion of revenue it receives from the traveling public—is just 26%, the lowest of any major U.S. transit agency. The fare increases are intended to bring that to 33% by 2021.

The public hearing will take place at 9:30 a.m. on March 29 at Metro headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. Those who’d like to comment in writing can send an email to [email protected] or a letter to: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, One Gateway Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90012-2932 Attention: Michele Jackson.

Posted 3/19/14

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink