This film could rock your world

August 13, 2014

Some movies launch with advertisements screaming from broadcasts, buses and billboards.

“Levitated Mass”— a documentary about the amazing journey of a 340-ton boulder into the hearts, minds and artistic consciousness of Southern California—is not one of those movies.

Although it tells a big, sprawling story about culture, community, bureaucratic challenges and engineering ingenuity, the documentary is going for more of a micro-targeted approach when it comes to publicizing its upcoming theatrical release.

As in: taking to the streets and putting up posters at points along the 105-mile-long “rock route” where large crowds gathered as the boulder slowly made its way to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in March, 2012.

By heading out to those neighborhoods with bright yellow posters reading “Remember when the rock rolled?” director Doug Pray is hoping to reunite some of the diverse characters who witnessed its epic journey from a Riverside County quarry to LACMA, where it now forms part of a monumental sculpture that has been visited by more than 600,000 people. (When the sculpture first was unveiled, 6,000 visitors flocked to the museum, setting an opening-day attendance record. It also sparked voluminous coverage, including this video on Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s website.)

Pray’s documentary, which premiered at the L.A. Film Festival last year, begins its theatrical release on Sept. 5 with a one-week run at the Nuart Theatre before moving on to play a number of other cities this fall. The documentary is one part art film focusing on the work of sculptor Michael Heizer, one part road movie, and one part behind-the-scenes docudrama about how the rock rolled (and almost didn’t.)

Some of its best moments come in interviews with people from all walks of life who weigh in on what to make of the new behemoth on the block. (The movie trailer offers a taste of their critiques.)

One woman theorizes that the massive white-wrapped object is not really a boulder at all but rather a suspicious giant artifact left over from a secret military base.

Some of those lining the streets see a colossal waste of money (though the $10 million project was privately financed) while others experience genius at work. Some detect the hand of God, and others glimpse a parable for all of life’s journeys.

Throughout, the film captures the sense of a slo-mo happening-in-progress that people across the Southland felt free to experience—sometimes right in their own front yards.

As one young girl put it: “Nothing really happens on this street, and now something amazing just happened.”

Beyond its chronicle of those who watched the rock roll through three counties and 22 diverse communities over the course of 10 days and nights, the film also offers some unusual inside footage: computer simulations of how the boulder would fare in an earthquake, artist Heizer interacting with workers installing the massive stone atop a concrete trench at LACMA, interviews with art world elites and donors, government officials grappling with seemingly impossible logistics, and some reality TV-style moments showing what happens when a transport truck’s transmission suddenly seizes up mid-voyage. (Spoiler alert: they figure out a way to get to a happy ending.)

Then there’s the boulder itself, which filmmaker Pray is only a little sheepish about dubbing a “rock star.”

“It’s as close as I’ve ever come to making an inanimate object into a character,” Pray said. “Because it kind of grows on you. It does have personality…It definitely became its own pop culture phenomenon. The whole joke of ‘the rock became a star,’ it’s a silly pun but the truth is it literally did.”

And, as big as the rock is, the film makes clear that it also fostered something even larger: a sense of community across our sprawling Southern California landscape.

“From wealthy neighborhoods to poor neighborhoods, from Riverside to Long Beach to downtown L.A.,” Pray said, “it was like the boulder itself kind of made this into a portrait of L.A.”

Posted 8/13/14

Our new social club—the L.A. River

August 13, 2014

Once banned from most of the L.A. River, kayakers are now a regular summer sight. Photo/StreetsblogLA

Most Angelenos know that the Los Angeles River is making a comeback. Still, the hipsters hawking free breakfast on its banks were a surprise.

Waving their arms and proffering scrambled egg sandwiches and muffins they’d cooked on a camp stove, the group of about a dozen young people were on the bike path near Rattlesnake Park on Saturday morning, flagging down cyclists for no apparent reason beyond community building.

“They said they had done it before, and had just decided to do it again,” said one passing cyclist, a 24-year-old from Eagle Rock who’s been riding along the river near Griffith Park for years. “It seemed like they were just, like, ‘Let’s just get together and do something nice.’”

Gathering at the river to do something nice has become a trend this summer, as momentum has built around the restoration and revitalization of L.A.’s long-suffering namesake waterway.

With scores of projects already complete and a $1 billion Army Corps of Engineers plan expected to dramatically improve an 11-mile stretch between downtown and Griffith Park, a nascent but notable scene has taken hold along the once-maligned L.A. River, particularly where it has been spruced up with pocket parks, hiking trails and bikeways.

This summer, for instance, kayaking tours are being offered in public recreation areas in the Sepulveda Basin and in Elysian Valley; later this month, about 100 stand-up-paddlers and rowers will gather in the Glendale Narrows for a first-ever L.A. River Boat Race.

The Los Angeles River Corp. is offering outdoor bike-in movies along the riverbanks later this month and has its second annual Greenway 2020 10k race scheduled for early November. Meanwhile, the Elysian Valley Arts Collective will host its annual Frogtown Art Walk again next month by the river. Nearby, Elysian, an underground restaurant that materialized two years ago on the river near Atwater Village, will be up and running, legally and officially.

Along the L.A. River's concrete banks, The Frog spot offers food, concerts and more. Photo/Franklin Avenue Blog

Elysian is also the home of Clockshop, a non-profit arts and cultural organization, and the site for more than a few weddings during the past year. And speaking of art, be on the lookout for the L.A. Mud People, a performance art group that frequents the river both as a medium and a backdrop.

“It’s really kind of miraculous,” marveled Lewis MacAdams, president of Friends of the L.A. River, which has itself drawn thousands of passersby over the past six weeks by staging free weekend concerts at The Frog Spot, an informal venue it set up this summer on Benedict Street along the Elysian Valley bike path.

“We’ve been surprised at how many people have showed up—probably 500 or so every Saturday and Sunday,” said MacAdams, adding that FOLAR will also be sponsoring a catch-and-release fishing event next month. “People are getting interested, and looking for community.”

MacAdams sees the interest as an outgrowth of the long political fight to restore the river, which was paved in the 1930s in an attempt to tame periodic but lethal floods. Nearly 4,000 people participated this year in FOLAR’s long-running annual river cleanup, he said—a record turnout—and each cleanup has helped spread the news of the river’s revitalization and potential.

So far, MacAdams said, most of the community activities have centered around FOLAR and the Elysian Valley arts community near Frogtown. “But a lot of it also is the bicycle population,” he said. “There are more bicyclists than we imagined, and they keep coming back.”

Julia Meltzer, executive director of Clockshop and the wife of David Thorne, who runs Elysian restaurant, agreed that the riverfront has become exponentially more active.

“There’s a lot more recreation and sporting,” she said, acknowledging that the various improvements, from friendlier landscaping to paved bikeways, have created occasional conflicts among walkers, cyclists, locals and other constituencies.

Nonetheless, a first-ever, free community campout along the river that Meltzer said she helped organize over Memorial Day weekend—along with California State Parks, the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, the Natural History Museum and others—was fully booked within an hour of its announcement.

“I think it’s the big buzz, and the opportunity to come down to the river’s edge legally now,” said MRCA Chief Ranger Fernando Gomez, adding that some 200 campers showed up on Memorial Day and that hundreds more have shown up this summer for MRCA river programs, ranging from free community paddles to evening weenie roasts in Marsh Park.

“It used to be that people weren’t allowed in the river without a special use permit—it wasn’t meant for recreation,” Gomez said. “People would look at the river and think it was disgusting.

“But now, they can go down in, say, a kayak, and they see that the water is actually pretty clean, and there’s a heron right over there taking off with a fish in its mouth. They see that it’s not just all about concrete anymore,” Gomez said. “It’s a river—a real live river—now and people want to be part of it.”

Posted 8/6/14

Seeking safe passage

August 13, 2014

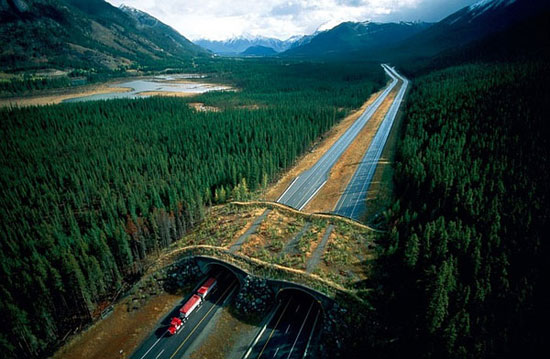

An overpass in British Columbia offers habitat linkage like that being sought here. Photo/Joel Sartore

For those on the front lines of preserving the vibrancy of wildlife in the Santa Monica Mountains, establishing a safe way for animals to get across the fast-moving 101 Freeway has been a long-held dream.

Some new developments may be pushing that vision closer to reality.

Galvanized by a series of mountain lion deaths in recent years, a multi-jurisdictional team is developing long-term strategies—including possible creation of the state’s first wildlife freeway overpass—as well as more immediate fixes to help link animals with their natural territories on either side of the 101.

Caltrans announced it has applied for a $2 million federal grant to fund environmental review and engineering design of a proposed “Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing” in Agoura Hills.

“US Highway 101 is an impassible barrier for wildlife migrating into or out of the Santa Monica Mountains. Animals with large home ranges, such as mountain lions, are essentially trapped within the mountain range, which can result in inbreeding and high mortality rates,” Caltrans said in announcing its grant application. “This wildlife crossing promises to provide for an improved habitat connection across a fragmented landscape, which will help sustain and improve the genetic diversity of mountain lions, deer, coyotes and other native species.”

The agency has previously applied unsuccessfully for federal funds to build a wildlife tunnel under the freeway. This time around, though, it’s seeking funding to study a range of alternatives, including the overpass. The cost and timetable of building such a structure have yet to be determined.

A decision on Caltrans’ grant application is expected before the end of the year. In the meantime, efforts are underway to jumpstart strategies that would make the crossing safer for animals even before an overpass is developed. They include:

- New and improved fencing to route animals away from the freeway and toward the existing underpass, Liberty Canyon Road.

- New vegetation around the existing underpass to also help lure animals away from the freeway and toward safety.

- Exploration of ways to enhance the wildlife-friendliness of the area, including eliminating lighting or placing it on timers.

- A commitment by the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains to provide architectural and landscape design services to help support the search for grant funding of the proposed new overpass.

“The idea is to have a robust crossing area,” said Clark Stevens, an architect who also serves as executive officer of the conservation district, which is working on the initiative with Caltrans, the Mountains Recreation & Conservation Authority and the office of state Senator Fran Pavley.

The stakes are high, both in the short term and over the long haul.

“What we’re interested in is making sure we continue to have a full complement of species in the Santa Monica Mountains, and that it doesn’t become an island of extinction,” Stevens said.

The overpass idea has been successfully implemented in other states, including Montana and Arizona, as well as in Canada, he said.

The proposed Liberty Canyon overpass, still in the preliminary planning stages, would be, in effect, “a piece of habitat over the freeway,” Stevens said. It could include a “guzzler” watering station for animals as well as chaparral and mature trees.

And, while animals would tend to use the crossing after-hours, humans could enjoy hiking over it during the day.

“One of the great things about it is it would allow a trail connection over the freeway that doesn’t exist anywhere else in that area,” Stevens said.

Many kinds of animals would be expected to use an overpass. But the survival and well-being of mountain lions—the Santa Monica Mountains’ “apex predator”—is particularly critical to the health of the overall ecosystem.

“Mountain lions are one of the ones that are most in need, and most in long-term danger because they exist at such low density and move over such long distances,” said Seth Riley, wildlife ecologist for the National Park Service’s Santa Monica Mountains Recreation Area. (Although mountain lions are rare in the Santa Monicas, he noted, they are common elsewhere in California and the U.S.)

Riley said scientists in the Santa Monicas currently are monitoring four adult mountain lions and two kittens via GPS-equipped collars. Another one-time resident, the male lion known as P-22, is believed to have traveled from the Santa Monicas across two freeways and into Griffith Park, where he is now at a “dead end” as far as breeding opportunities, Riley said.

By surviving that journey, P-22 is one of the lucky ones.

The current wildlife crossing efforts were galvanized by the death last October of another male mountain lion, who is believed to have made it across the 101 at Liberty Canyon, only to be forced back onto the freeway and killed after he encountered a fence he could not scale. Earlier this year, three mountain lion kittens also were killed on L.A. County roadways.

Other notable casualties include a young male lion who was shot and killed by police officers after he found his way into a courtyard in Santa Monica in 2012, and another, known as P-18, who was struck and killed by a car on the 405 Freeway near the Getty Center in 2011.

In some ways, it’s remarkable that the species has been able to survive at all in L.A.’s urban sprawl, Riley said.

“It’s an amazing thing that a large carnivore persists in Los Angeles,” he said. “If that were to be lost, that would just be a huge spiritual and aesthetic loss, I think.”

New measures aim to make life safer for even the littlest mountain lions. Photo/National Park Service

Posted 7/31/14

Cracking the ER “Code”

August 13, 2014

In the beginning, the idea was simply to produce some archival footage—a project pitched by a young medical student to document life-saving efforts unfolding amid the controlled chaos of the emergency room at Los Angeles County’s old General Hospital.

It was there, on the edge of downtown, that the concept of emergency medicine was born in 1971 and, in some respects, had remained the same in theory and practice throughout the ensuing decades.

Despite medical modernizations that had become the norm at most hospitals, the emergency crew at the renamed Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center still operated more like a battlefield MASH unit. Crowds of doctors and nurses swirled around patients suffering the most catastrophic of injuries. Side by bloody side, the stricken were packed into a cramped trauma bay in the ER called “C-booth,” with barely a curtain between them.

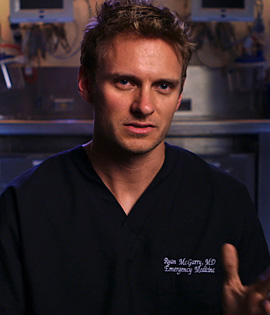

But in 2008, all that was about to change, and first-year resident Ryan McGarry, who also had a keen interest in filmmaking, wanted to capture the era before it was gone. Because of earthquake damage to the old county hospital, the emergency department was moving next door to a new state-of-the-art facility that would rocket the doctors into 21st century medicine, complete with its emphasis on patient privacy and layers of paperwork.

Although initially modest in scope, McGarry’s ambitions for the project soared with the support of top Los Angeles County officials and the help of a producing team that included USC Distinguished Professor Mark Jonathan Harris, who has won three Academy Awards for documentaries.

McGarry’s film, Code Black, opened nationwide in June and has become a critical success, a gripping and graphic look at the shifting world of emergency medicine for the destitute and working poor who rely on public hospitals, such as County-USC, for their care. The term Code Black refers to the hospital’s designation for the highest level of emergency room crowding. Among other honors, the film won the Jury Award for best documentary at the 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival.

Focusing on a cadre of idealistic young residents, including himself, McGarry explores the challenging new realities for the next generation of emergency room physicians as they remain committed to maintaining a personal connection with patients while confronting the escalating regulatory demands and settings that emphasize patient privacy.

Dr. Sean Henderson, chairman of the hospital’s emergency department, says his 21-year-old daughter saw the documentary at a film festival in Santa Barbara and was so inspired that she changed her major.

“She decided to become a physician’s assistant because of that movie,” he said.

“Often, doctors are portrayed as overpaid snobs who don’t really care,” he continued the other day, sipping a caffeine-free Coke in his office in the old county hospital. “But I think you’ll see in this movie that this is not always the case. There are people doing things because they really care about the people they serve.”

Still, Henderson said he has some personal reservations about the film—a project he inherited from his predecessor, Edward Newton—and isn’t sure he would have green-lighted it himself.

“I’ve never believed in cameras in the hospital,” he explained. “The fact that you’re in an emergency room with an unplanned, unscheduled, unanticipated event—stressed, waiting, probably less informed than you’d like to be—I think that’s a very vulnerable place to be.”

That said, Henderson praised the filmmaker for getting two sets of consents from patients whose emergency room visits are shown in the film—everyone from a drunken man belting out a romantic ballad in the waiting room to the family of a patient whom doctors unsuccessfully fought to save as they cut into his chest to keep his heart beating.

Henderson, who became department chair in 2012, also appears in the film, but mostly to defend a prominently featured action he imposed in the face of a severe nursing shortage. In a dramatic segment of the documentary, he shut down an area of the new emergency department, creating a monumental patient backlog, to make the point “that we couldn’t continue to care for all these people with inadequate resources.”

“I caused the crisis and I had to defend the crisis. I was the villain,” he said, and then offered a fuller explanation of his actions than he did in the film.

He said that in the past, before Health Services Director Mitchell Katz’s arrival in 2011, “the way you got attention in the county system was to create a crisis. It wasn’t just me. It was throughout the system…If you have a crisis, resources are pulled from someone who’s not having a crisis to take care of your crisis. And so, without permission from the school [USC] or the county, I created a crisis knowing full well that it would create a pushback downtown that would allow them to hear my pleas that heretofore had gone ignored.

“It was manipulative, it was sneaky, and mea maxima culpa. But it worked,” he said, noting that more funding was soon made available for the desperately needed nurses.

Another top L.A. County emergency department official, Dr. Erin Wilkes, said she’s seen her good friend McGarry’s film more than a dozen times in various stages along the way. The two were residents together, beginning in the old hospital’s emergency department. Today, she’s the director of Emergency Medicine Systems Innovation & Quality.

Wilkes said she helped organize various Code Black screenings for county officials, including the Health Services executive team. The feedback was mostly positive, she said, although “there were a lot of questions about what the consent process was like.” Wilkes said McGarry obtained his first consents at the hospital and then got a second round of permissions after showing people the actual footage he wanted to use.

Wilkes said she’d now like to build on Code Black’s positive buzz by holding a panel discussion event at USC that would include McGarry, now an assistant professor of emergency medicine at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a recent interview with the emergency medicine publication ACEPNow, McGarry talked about the demands of simultaneously pursuing his residency and filmmaking. “It was three years of no vacation,” he said. But he said he had no regrets.

“One thing that I feel very lucky to have experienced,” he said, “is nonmedical people sitting through some pretty tough stuff in cases we show. And at the end of the film people give us a standing ovation. I wish I could share that with every physician, nurse and X-ray tech who leaves a really tough shift.”

Posted 7/17/14

A park vote to keep the green flowing

August 6, 2014

From the Malibu Pier to trails running through the Santa Monica Mountains, from a dog park in La Crescenta to a skate park in Downey, two L.A. County park measures have generated nearly $1 billion in improvements over the past two decades for some of the region’s best-loved gathering places, great and small.

The measures—Proposition A in 1992 and a follow-up initiative known as “Baby A” in 1996—have helped to fund 1,545 projects across the county including “tot lots,” tree planting, swimming pools, soccer fields, bikeways and fitness gardens, along with facilities for seniors and youth, wildlife habitat projects and graffiti abatement services.

Among the measures’ most broadly visible success stories: a new shell installed at the Hollywood Bowl, a county park, in 2004; the extensive restoration of the Griffith Observatory, which reopened to the public in 2006; and expansion of the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area, with amenities including a play area and ball fields. Prop. A funding also has helped transform El Cariso Community Regional Park in Sylmar, which now boasts new features including soccer fields and a 15,000-square-foot community center and gymnasium. And it is allowing kids to make a splash this summer in the new Olympic-sized pool at Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles.

But the flow of green amenities to parks in L.A. County’s unincorporated areas and its 88 cities could be coming to an end, with Prop. A set to expire next June 30. (Its 1996 counterpart will finish in 2019.)

Concerned about derailing a successful program of investing in local parks and recreation facilities, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors decided this week to place on the November ballot a measure that would essentially carry on the 1992 Prop. A for 30 more years, generating a similar $53 million per year.

“We need to do this if we want to keep the momentum going,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who along with Supervisors Don Knabe and Gloria Molina voted to place the measure on the Nov. 4 ballot. “The public has benefitted from this. They like the parks that have been built. They like the recreational opportunities that have been provided. I don’t think they want to see this come to a grinding halt on June 30 of this coming year.”

But Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who joined Mark Ridley-Thomas in opposing the action, said it was too soon to place what he called a “half-baked tax” before the voters, especially since Prop. A ’96 is continuing for several more years and some unspent funds remain in Prop. A coffers.

Russ Guiney, the county’s director of Parks and Recreation, acknowledged that there is a current balance of $154 million in Prop. A funds, but said $20 million of that is committed to upcoming projects. Unless the proposed continuation of Prop. A passes, the remaining funds will be spent down rapidly on park projects and maintenance demands that run around $55 million annually, Guiney said.

The average homeowner currently is assessed $13 a year for Prop. A ’92 and $7 annually for Prop A. ’96, for a total of $20 a year. The measure now heading to the Nov. 4 ballot would replace the Prop. A ’92 assessment with a flat tax of $23 a year per parcel. If passed by the required two-thirds of county voters, that would bring the average homeowner’s total tab for park improvements to $30 per year.

Guiney noted that 64% of voters approved the 1992 measure, and even more—65%—voted in favor of the 1996 proposition.That bodes well, he said, especially since so many projects built with funds from the previous parks measures are now visible and being used enthusiastically by the public.

“I think the voters understand and appreciate this, based on past history,” he said. “We’re optimistic.”

Posted 8/6/14

In the interest of real oversight

August 5, 2014

Max Huntsman, testifying Tuesday, is the first inspector general, a position that carries high expectations.

The Board of Supervisors voted 3-2 to reject a proposal to create a new citizens’ commission to oversee the Sheriff’s Department, a proposal I opposed. Here, in a statement I read during Tuesday’s board meeting, is why:

Ensuring constitutional policing, and the accountability and transparency that promotes it, has long been one of our society’s–and especially Los Angeles’–most difficult challenges. Law enforcement agencies, which have the extraordinary power to take away our freedoms, to use deadly force, to collect information on private citizens, must be held to the strictest standards of law.

Each of us serving in public office takes an oath to uphold the constitutions of the United States and the State of California. For me, that oath has a very personal meaning because many years ago, before I ever was elected to office, my rights as a private citizen were violated by a local police agency. As an elected official, I spilled considerable political blood–even as others were spilling real blood–when I took on such police abuses as excessive force, bad shootings, reckless use of chokeholds and illegal spying on law-abiding citizens.

Today’s upheaval in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department is only the latest in a series of crises that have engulfed our local law enforcement agencies over the years. When jail violence and other misconduct issues shook the Sheriff’s Department, this board, on a motion I authored with Supervisor Ridley-Thomas, established the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence to recommend steps to reverse the department’s slide into scandal. The commission produced a hard-hitting report on what its esteemed members concluded was necessary to hold the Sheriff’s Department accountable for how it polices our jails and, by extension, our communities. Our board unanimously approved each and every one of those reforms, most of which have been implemented, some of which remain works in progress.

Today’s discussion focuses on this very question: What is the most effective way to ensure that the department strictly adheres to its constitutional mandate while conducting itself with as much transparency as possible to restore public confidence. The problem with the Sheriff’s Department is not that there is too little oversight. The problem is that there’s been too little effective oversight.

Since 1959, before the now-notorious Men’s Central Jail was even opened, the County’s Sybil Brand Institutional Inspection Commission has been charged with monitoring our jails. After the 1992 Kolts Report, which focused on excessive force, community relations and citizen complaints, the Board of Supervisors hired Special Counsel Merrick Bobb to track these issues and produce semi-annual reports. The Board also created an Office of Ombudsman to hear and vet citizen and inmate complaints. Later, the Board engaged the ACLU as an independent jail monitor–so independent, in fact, that the ACLU would periodically sue us over the very conduct they were monitoring on our behalf.

Later still, we created an Office of Independent Review, a group of attorneys operating within the Sheriff’s Department to provide a second set of eyes on the department’s internal investigations of alleged and potential misconduct. And on top of all this, the U.S. Department of Justice has been looking over our shoulder for years on a variety of matters, including whether the department is meeting its obligations under a Memorandum of Agreement in its treatment of mentally ill inmates.

Despite these oversight efforts, the Sheriff’s Department went into a tailspin that included: the failed administration of our jails; violence perpetrated against some of our inmates and jail visitors, and a lack of adequate and effective treatment of inmates with mental health issues. This is not to mention problems elsewhere in the department that made it a poster child for how not to carry out its constitutional responsibilities.

It was in response to this meltdown that I proposed the creation of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence. After nearly a year of dedicated work under the leadership of some of L.A.’s most respected jurists, experts and community leaders, the panel urged enactment of more than 60 reforms. The centerpiece was the establishment of a new, full-time Office of Inspector General that would be independent of the Sheriff’s Department, answering directly to the Board of Supervisors, with its own staff, budget and broad investigative authority, including unfettered access to the department’s records.

Those recommendations did not include the creation of a sheriff’s oversight commission, like the one now being proposed. In fact, the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence concluded in its final report: “While the Commission considered a civilian commission comprised of community leaders as an additional oversight body, such a commission is not necessary if the Board of Supervisors continues to put a spotlight on conditions in the jails and establishes a well-structured and adequately staffed Office of Inspector General.”

But the ink was barely dry on this historic report before this Board was asked to consider the creation of a sheriff’s oversight commission. A year later, before the Board had even appointed an Inspector General, a second motion was proposed, calling again for the creation of a sheriff’s oversight commission. And now, just as the Board is preparing to formally establish the Office of Inspector General, we once again are being told that only a sheriff’s oversight commission can really do the job.

I understand the deep and long-held frustrations that have led to this proposal. I share them. Long before the scandal over brutality in the jails erupted, residents in some neighborhoods complained of heavy-handed tactics by the Sheriff’s Department. In recent days, we have all heard from many people who support the idea of a new oversight panel, and I applaud them for their active engagement in an issue of such critical importance. But I believe it is necessary at this moment of understandably high emotions to provide straight talk about what I see as the surest way to reach our goal of righting the Sheriff’s Department for today and the future.

Some of you might ask: What’s the harm? Isn’t too much oversight better than too little? But that’s been precisely the problem—not too much oversight, but too much inadequate, ineffective and duplicative oversight. Somehow, with the many monitoring efforts launched over the years, problems were overlooked, ignored or never addressed. In my judgment, the ambiguous roles of these various oversight structures contributed to a lack of focus and decisiveness in addressing the department’s problems, which have now become a national embarrassment.

Simply put, when everyone is in charge, no one is in charge.

This is why the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence urged the creation of the Office of Inspector General, an agency with authority, resources and a single-minded dedication to our collective mission of restoring constitutional policing to our County. Today, more than seven months after we appointed our Inspector General, we finally have before us on our agenda a staffing and organizational plan for his office. In addition to providing rigorous oversight of the Sheriff’s Department, his mandate includes reaching out to the public through town hall meetings and other vehicles to hear complaints and investigate.

The Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, the acting Sheriff, the County’s CEO and our own Inspector General all agree that the first priority must be to get this new office fully operational before contemplating any additional oversight proposals.

These are the indisputable facts: the proposed sheriff’s oversight commission would have no real power, no legal investigative authority, only limited access to sensitive department materials and no meaningful way to implement any recommendations it might make. The state constitution grants great power to the Sheriff, and he is not subordinate to the Board of Supervisors. And this Board cannot delegate powers to a commission that the Board itself does not possess.

Finally, looming ahead, there is a potential for oversight, beyond the Inspector General, with very real and sharp teeth. The U.S. Department of Justice has been investigating key areas of the Sheriff’s Department for a number of years. While it has noted some progress toward reform, it recently warned of serious deficiencies. It is becoming abundantly clear that the Justice Department will compel the department and this County to be accountable for constitutional policing through a consent decree or a Memorandum of Agreement, all under the supervision of a federal judge.

We must permit the Inspector General, the Justice Department and this Board to implement the system of accountability recommended by the jail violence commission nearly two years ago. Creating any additional structure would be counterproductive. These entities, working in tandem, offer the best chance of establishing the kind of accountability and transparency that we all want. If this system falls short, then our Board can reassess any number of alternatives, including legislative changes at the state and county levels that would allow for an oversight body with real authority over the Sheriff’s Department.

This much I know for sure, the commission we’re being asked to create today would be unable to live up to our highest—and rightful—expectations.

Posted 8/5/14

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information