Hospitals & Clinics

At the ready for Ebola in L.A. County

October 17, 2014

Nurses at LAC+USC hospital this week learn how to protect themselves from Ebola with protective gear.

When LAC+USC Medical Center handed out its latest batch of protective gear against the Ebola virus Wednesday, several emergency room nurses eagerly reached out with both hands.

There were impermeable gowns, scarves, booties, hair coverings, face shields, goggles and gloves – boxes and boxes of them. Still, the offered protections were not enough to ease the anxieties of at least a few of the nurses who’d gathered in the facility’s conference room.

After all, two members of their profession had, stunningly, contracted Ebola in a well-known Dallas hospital while extensively treating a patient who would succumb to the deadly disease.

One of the nurses at the LAC+USC training session, for example, worried whether the back of her neck was still exposed after she’d slipped on her blue gown. A tall, male nurse, meanwhile, wondered what might happen if his large feet tore through his protective booties.

Observing the session was nurse Jason Guzman, 33, who’d already been training for more than a week at the Los Angeles hospital, which is operated by the Department of Health Services. He understood the importance of those questions and concerns because before his training, he had them, too. For with Ebola, even the slightest wardrobe malfunction can lead to infection.

The training, he said, “helped me get more comfortable with the gear. It’s really boosted my confidence. It’s helped me feel a bit better about the situation.”

According to the World Health Organization, the current outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease has infected some 8,900 people, killing about 4,500 of them. That’s more than all other previous Ebola outbreaks combined. Among the casualties: 256 healthcare workers.

Although West Africa remains the epicenter of the disease, the patient in Dallas succumbed after a visit to Liberia, infecting two nurses who’d cared for him.

According to Los Angeles County’s interim health officer, Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, the nurses’ infections underscore the need for healthcare workers and others to take extreme precautions if they come into contact with a patient who may be contagious.

“I feel personally responsible for their safety,” he said.

Ebola, first discovered in 1976, can cause fatal hemorrhagic fever. A person can get sickened through direct contact with an infected person’s bodily fluids. The first symptom is fever, followed by headache, weakness, diarrhea and severe bleeding.

Gunzenhauser is concerned but calm, even unruffled. That may be because he’s not only a doctor but a retired Army colonel, whose resume includes graduation from West Point, medical training at Walter Reed Army Hospital and drafting health policies for soldiers deploying to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He even learned to parachute out of planes, should that be the only way to reach wounded soldiers on the battlefield.

“Coming out of the military, I’m very accustomed to working in highly stressful operational environments and approaching problems with greatly detailed plans,” he said.

Last week, Gunzenhauser and other county leaders convened a task force to evaluate the response to Ebola if it were to reach Los Angeles. He knows that patients would need more than just medical care.

That’s why beyond medical, emergency and law enforcement agencies, the task force includes such departments as Children and Family Services, Mental Health and Public Social Services.

“Let’s say, for example, we might have a case where we would need to quarantine a family,” he said. “How are they going to get their food? What if they need medications? What if we’re pulling a kid out of school? We need to look at all those contingencies, and plan for them.”

If preparing for Ebola is like mounting a military campaign, then nurse Jason Guzman is among those on the front lines. He feels a “calling” to be a nurse, despite knowing that taking risks is “part of the job description.”

“Nurses are in the field to care for those who need help, and Ebola patients aren’t any different,” Guzman said. “They definitely need care — a little bit more care, perhaps.”

“I just know that if there’s a situation where there’s possibly a patient with Ebola, I’m going to do everything i can to help them,” Guzman said. “I’ll also definitely do everything I can to protect myself.”

Posted 10/17/14

Cracking the ER “Code”

August 13, 2014

In the beginning, the idea was simply to produce some archival footage—a project pitched by a young medical student to document life-saving efforts unfolding amid the controlled chaos of the emergency room at Los Angeles County’s old General Hospital.

It was there, on the edge of downtown, that the concept of emergency medicine was born in 1971 and, in some respects, had remained the same in theory and practice throughout the ensuing decades.

Despite medical modernizations that had become the norm at most hospitals, the emergency crew at the renamed Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center still operated more like a battlefield MASH unit. Crowds of doctors and nurses swirled around patients suffering the most catastrophic of injuries. Side by bloody side, the stricken were packed into a cramped trauma bay in the ER called “C-booth,” with barely a curtain between them.

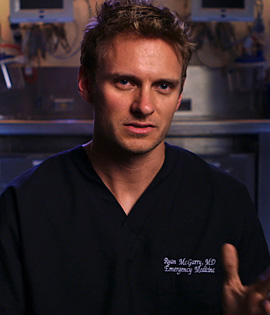

But in 2008, all that was about to change, and first-year resident Ryan McGarry, who also had a keen interest in filmmaking, wanted to capture the era before it was gone. Because of earthquake damage to the old county hospital, the emergency department was moving next door to a new state-of-the-art facility that would rocket the doctors into 21st century medicine, complete with its emphasis on patient privacy and layers of paperwork.

Although initially modest in scope, McGarry’s ambitions for the project soared with the support of top Los Angeles County officials and the help of a producing team that included USC Distinguished Professor Mark Jonathan Harris, who has won three Academy Awards for documentaries.

McGarry’s film, Code Black, opened nationwide in June and has become a critical success, a gripping and graphic look at the shifting world of emergency medicine for the destitute and working poor who rely on public hospitals, such as County-USC, for their care. The term Code Black refers to the hospital’s designation for the highest level of emergency room crowding. Among other honors, the film won the Jury Award for best documentary at the 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival.

Focusing on a cadre of idealistic young residents, including himself, McGarry explores the challenging new realities for the next generation of emergency room physicians as they remain committed to maintaining a personal connection with patients while confronting the escalating regulatory demands and settings that emphasize patient privacy.

Dr. Sean Henderson, chairman of the hospital’s emergency department, says his 21-year-old daughter saw the documentary at a film festival in Santa Barbara and was so inspired that she changed her major.

“She decided to become a physician’s assistant because of that movie,” he said.

“Often, doctors are portrayed as overpaid snobs who don’t really care,” he continued the other day, sipping a caffeine-free Coke in his office in the old county hospital. “But I think you’ll see in this movie that this is not always the case. There are people doing things because they really care about the people they serve.”

Still, Henderson said he has some personal reservations about the film—a project he inherited from his predecessor, Edward Newton—and isn’t sure he would have green-lighted it himself.

“I’ve never believed in cameras in the hospital,” he explained. “The fact that you’re in an emergency room with an unplanned, unscheduled, unanticipated event—stressed, waiting, probably less informed than you’d like to be—I think that’s a very vulnerable place to be.”

That said, Henderson praised the filmmaker for getting two sets of consents from patients whose emergency room visits are shown in the film—everyone from a drunken man belting out a romantic ballad in the waiting room to the family of a patient whom doctors unsuccessfully fought to save as they cut into his chest to keep his heart beating.

Henderson, who became department chair in 2012, also appears in the film, but mostly to defend a prominently featured action he imposed in the face of a severe nursing shortage. In a dramatic segment of the documentary, he shut down an area of the new emergency department, creating a monumental patient backlog, to make the point “that we couldn’t continue to care for all these people with inadequate resources.”

“I caused the crisis and I had to defend the crisis. I was the villain,” he said, and then offered a fuller explanation of his actions than he did in the film.

He said that in the past, before Health Services Director Mitchell Katz’s arrival in 2011, “the way you got attention in the county system was to create a crisis. It wasn’t just me. It was throughout the system…If you have a crisis, resources are pulled from someone who’s not having a crisis to take care of your crisis. And so, without permission from the school [USC] or the county, I created a crisis knowing full well that it would create a pushback downtown that would allow them to hear my pleas that heretofore had gone ignored.

“It was manipulative, it was sneaky, and mea maxima culpa. But it worked,” he said, noting that more funding was soon made available for the desperately needed nurses.

Another top L.A. County emergency department official, Dr. Erin Wilkes, said she’s seen her good friend McGarry’s film more than a dozen times in various stages along the way. The two were residents together, beginning in the old hospital’s emergency department. Today, she’s the director of Emergency Medicine Systems Innovation & Quality.

Wilkes said she helped organize various Code Black screenings for county officials, including the Health Services executive team. The feedback was mostly positive, she said, although “there were a lot of questions about what the consent process was like.” Wilkes said McGarry obtained his first consents at the hospital and then got a second round of permissions after showing people the actual footage he wanted to use.

Wilkes said she’d now like to build on Code Black’s positive buzz by holding a panel discussion event at USC that would include McGarry, now an assistant professor of emergency medicine at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a recent interview with the emergency medicine publication ACEPNow, McGarry talked about the demands of simultaneously pursuing his residency and filmmaking. “It was three years of no vacation,” he said. But he said he had no regrets.

“One thing that I feel very lucky to have experienced,” he said, “is nonmedical people sitting through some pretty tough stuff in cases we show. And at the end of the film people give us a standing ovation. I wish I could share that with every physician, nurse and X-ray tech who leaves a really tough shift.”

Posted 7/17/14

Making kids’ trauma less traumatic

September 11, 2012

Jordan made a full recovery from the head injury for which he was treated at the pediatric trauma center.

JoAnn Hanson-Nortey got the awful phone call a year ago this week: Her 10-year-old son, Jordan, running full-tilt on the playground, had collided with another child and suffered a severe head injury.

“It was a freak thing,” recalls the Sherman Oaks mother. “They had banged heads running around a wall. You wouldn’t think it would be that serious, but it caused a skull fracture—the neurosurgeon said it was like a crack in an eggshell.” Had he not received immediate treatment, he could have suffered permanent brain damage or worse.

Instead, emergency medical technicians swiftly transported both Jordan and the other child, who also was seriously injured, to Northridge Hospital’s Richie Pediatric Trauma Center, which celebrates its second anniversary on October 4.

Championed by Los Angeles City Councilman Richard Alarcon with crucial assists from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, state Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Pacoima) and others, the center is one of only seven such units in Los Angeles County. It is also the first and only one to serve the San Fernando Valley’s littlest trauma patients, who until the center’s 2010 opening had to be airlifted to UCLA’s pediatric trauma center or to Children’s Hospital in Hollywood.

“We have saved some real lives,” says Northridge Hospital’s interim president, Saliba Salo, noting that the so-called “golden hour”—the 60-minute window right after an injury in which quick treatment can make a life-or-death difference—is doubly important for children. Indeed, pediatric patients are so much more fragile that doctors refer to their window as the “platinum half-hour.”

“In the fiscal year before we opened the unit, we saw only eleven kids under age 14 for trauma,” says Salo. “But in fiscal year 2011, we saw 151, and we anticipate 155 this year.”

The center has been a longtime goal for the Valley, where doctors, first responders and community leaders advocated for years for its opening. Alarcon, in fact, made it a personal crusade after his 3-year-old son, Richie, was gravely injured in a 1987 car crash on Victory Boulevard; a suicidal driver rammed into the car in which the baby was riding, and because there was no pediatric trauma unit nearby, the little boy’s treatment was delayed while he was airlifted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he died the next day.

In 2005, Alarcon—who by then was in the state senate—introduced a bill to authorize California counties to levy a surcharge on traffic tickets, a portion of which would fund pediatric trauma centers. The bill was vetoed, but Alarcon introduced it again in 2006.

This time it passed, and when it was scheduled to expire three years later, Padilla authored an extension. Los Angeles County Supervisors, meanwhile, agreed to levy the fine here, and to tap the so-called “Richie’s Fund” revenue to help launch the unit. Although private donations to the hospital remain crucial, the county’s funding distribution to its trauma and emergency care network has since included $1.6 million in startup operating funds for the center in 2011 and $1.74 million this year.

County health officials report that the Northridge unit not only hastens care for the Valley’s trauma victims, but also shortens wait times at the county’s other trauma care units by lightening the patient load elsewhere. Before Northridge Hospital was certified as a pediatric trauma center, every young trauma patient in the Valley or even points north of the county line had to be transported long distances to receive care, usually to Children’s Hospital in Hollywood or to UCLA. This year, nearly 42% of them have remained in the Valley for treatment.

The unit this year treated children from 47 cities and from as far away as Sacramento County, though the bulk of its patients come from the Valley. That proximity is key because having family members at hand plays a big part in a child’s recovery, says Melanie Crowley, who manages the hospital’s trauma program.

“If you or I had a child transported to UCLA or Children’s, we might wonder which car we were going to take to the hospital to see them,” says Crowley. “But a lot of our families don’t even have cars. They have to decide which bus to take.”

Crowley says the center’s cases run the gamut. “But the ones that stick in my mind are the ones that happen just because of the normal things that kids do. Kids who were just jumping on the couch when they fell and got a bleed on the brain. Kids who chased a ball out onto the street and got hit by a car. Kids injured because a car seat was installed improperly.”

And kids like Jordan, who, because the Richie Center existed, was getting a CT scan in preparation for neurosurgery within 45 minutes of his accident.

“The doctor literally called me from his car on the way to the hospital to explain the operation,” recalls Hanson-Nortey, a single mother who remained at her son’s bedside, 24-7, for the next five days. After some physical therapy, he was home, and 3 months later, Jordan was back to school full-time.

“I probably could have gone back in like a month,” the now-11-year-old boy says, “but my mom wanted to be safe.”

Since then, his scars have healed, his hair has grown back and he plays tennis and begs his mother to let him play football—in vain. She says she has seen a side of her son that is braver than she had ever imagined; he says he’d like to be a policeman someday.

“I wasn’t that scared because I knew the doctors were going to make me better,” he says now. His mother’s perspective is slightly different.

“The people at the hospital turned something really awful into something that was just pretty bad that we could get over,” she says.

Posted 9/11/12

Urgent need, serene space

August 11, 2011

Most of us are familiar with “urgent care” as the place to go when a medical situation’s not dire enough for the emergency room—but too serious to ignore.

Now apply that concept to mental health issues and you’ll have a picture of what the county’s now offering in a newly-opened facility.

The Olive View Community Mental Health Urgent Care Center, located at 14659 Olive View Drive in Sylmar, is expected to serve 5,000 people a year and to relieve crowding in the psychiatric emergency room of the nearby Olive View-UCLA Medical Center by assessing and treating patients in psychological distress, as well as helping them to swiftly secure follow-up care.

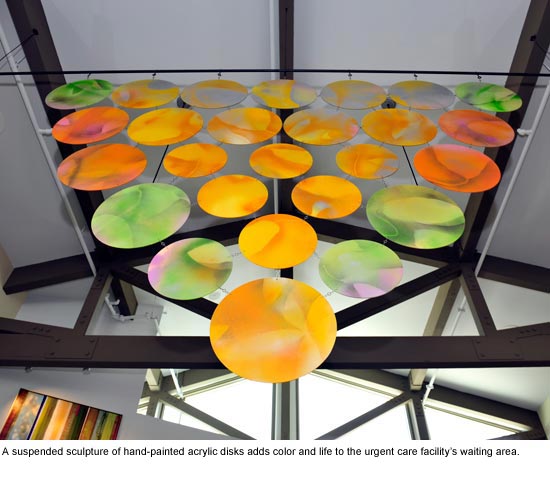

The facility is not just state of the art, it’s full of art—funded under the county’s Civic Art policy and created by Amy Trachtenberg and Jeffrey Miller. Artful elements in the new center explore bright yet soothing motifs, imbued with natural elements. The message—architecturally, artistically and clinically—is one of healing and hope.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which has earned LEED silver certification—will serve clients from the San Fernando, Santa Clarita and Antelope Valleys. The new facility will allow the county to serve an additional 2,000 people a year. Its opening comes as economic pressures and joblessness are adding stress to the lives of many.

“Opening this new mental health facility today could not have come at a better time. It’s not a moment too soon,” Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said. “Demand for our services is going up.”

Here’s a look at the new facility, inside and out:

Posted 8/11/11

New health chief rolls into town

November 4, 2010

In the public imagination, San Francisco and Los Angeles have long been California’s odd couple. They’ve got cable cars, we’ve got freeways. They’ve got cioppino, we’ve got burgers. They’ve got the pennant-winning Giants, we’ve got…oh, never mind.

But soon San Francisco and L.A. will have someone very important in common:

Dr. Mitchell Katz.

Katz, San Francisco’s top health official since 1997, is set to leave the City by the Bay to become L.A. County’s director of health services in January.

His charge: to lead the vast county health care system into the future—fast. In the course of the next three years, Katz and his department will seek to reshape how care is delivered here. That means implementing national health care reforms that emphasize preventive care and increase access to outpatient services rather than continuing to pour resources into the large public hospitals that have long been the cornerstones of the L.A. system.

“Something I’d like to work on in Los Angeles is creation of a comprehensive ambulatory care system that includes both the private providers and the public providers,” Katz said, describing the county as the “glue” that would unite the systems. “Every clinic has to be clearly connected to a hospital that takes their referrals.”

He also wants to create a “system of record” in which each patient will have a “primary care home” and medical records in a centralized registry. That will make it easier for providers to know, for example, which patients have diabetes and to make sure they keep up with the eye exams their condition requires.

Katz, 50, said he is a “change agent, not a figurehead.” Even as San Francisco’s top health official, he still makes a point of working as a hands-on doctor for about one day a week—something that the Harvard Medical School grad intends to keep doing when he gets to L.A.

“You find out what’s working and what isn’t,” he said. Moreover, the frontline work creates credibility and a sense of shared understanding with the staff—which are important when it comes time to propose new ways of doing things.

“The natural response to an administrator is ‘You don’t know what it’s like to take care of our patients.’ Well, no one ever says that to me.

“When I’m in my room, I have my stethoscope, my prescription pad. I’m like anyone else.”

Katz, who will earn $355,000 a year in L.A., was recruited to come here two years ago but declined, citing unfinished work in San Francisco. That included seeing through the implementation of the award-winning Healthy San Francisco, a voluntary universal healthcare program that provides coverage to more than 54,000 people.

Katz, who will earn $355,000 a year in L.A., was recruited to come here two years ago but declined, citing unfinished work in San Francisco. That included seeing through the implementation of the award-winning Healthy San Francisco, a voluntary universal healthcare program that provides coverage to more than 54,000 people.

Making the move now, he said, just “feels right.” Many in the Los Angeles County Health Department, which is battling a large deficit and has not had a permanent leader for more than two years, have reached out to him by phone or email since his appointment, offering to do “everything they can to help me,” Katz said.

While Katz believes L.A. and San Francisco are far from polar opposites from a health care perspective—“I think they are more alike than different”—he knows that his management approach will have to change somewhat when he makes the move.

“I’m a very hands-on person,” Katz said. “I know every single health center in San Francisco that’s part of my department. Most of them I’ve actually worked in as a doctor. I can bicycle to any of them.”

In L.A., “I have to think of a completely different way to be. You can’t do a lot of walking around when it takes two hours to drive somewhere.”

The county’s vast sprawl can be even more daunting if you’re a self-described bad driver.

“I’m terrible!” Katz said. “It’s certainly going to be a challenge to me.”

Katz, a committed bicycle commuter in San Francisco, said he can often be seen pedaling around town in tie and jacket, his backpack stuffed with papers. “It’s not unusual,” he said, “for someone to yell out, ‘Hi, Dr. Katz!’ “

After he moves to L.A. in January (his partner, Igael Gurin-Malous, a teacher, and their kids Maxwell, 8, and Roxie, 6, will join him when the school year is over) Katz intends to continue his cycling ways.

He’s looking for a house in a neighborhood, perhaps Silver Lake or Los Feliz, that’s within biking distance of his new office and County-USC Medical Center. He knows he will need to get behind the wheel to get to more far-flung hospitals such as Olive View-UCLA Medical Center in Sylmar. “I’ll just have to do it,” he said.

But he doesn’t sound like he’s planning to become a Southern California car culture convert any time soon.

“I do not love cars,” he said. “I think that the world would be a better place if more people bicycled.”

Posted 10/25/10

State wins billions in needed federal health aid

November 3, 2010

After more than a year of tortuous negotiations between state and federal health officials, it was announced this week that California will receive $10 billion in health aid during the next five years through the renewal of its ongoing Medicaid waiver.

After more than a year of tortuous negotiations between state and federal health officials, it was announced this week that California will receive $10 billion in health aid during the next five years through the renewal of its ongoing Medicaid waiver.

The infusion of new federal funding will expand health coverage for uninsured low-income residents, improve access and quality of care for seniors and the disabled, and help implement federal health care reform when its new rules take effect in 2014.

The negotiations took place between the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services and California’s Department of Health and Human Services.

The County of Los Angeles—constituting roughly 30% of the state’s population but 34% of the state’s medically indigent and 36% of those living below the federal poverty level—will be a major beneficiary of the aid. Those funds have helped to underwrite the County’s continuing reform and restructuring efforts since 1995, when the Clinton Administration granted the initial five-year federal waiver under Section 1115(a) of the Social Security Act.

That waiver allowed Los Angeles County to reconfigure its health-care services, creating public-private partnerships with non-profit community-based clinics and expanding ambulatory and outpatient services with federal money. This was accomplished by “waiving” federal requirements that had restricted the funding to reimbursement for in-patient hospital services, the costliest type of medical care.

To learn more about the recently approved agreement, formally known as California’s “Bridge to Reform: A Section 1115 Waiver Proposal,” visit the California Department of Health Care Services site here.

Posted 11/03/10

Cash infusion will let TB ward open

September 29, 2010

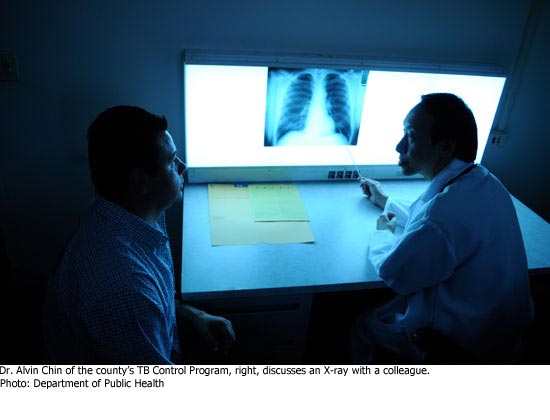

Supervisors on Tuesday approved $1.1 million to staff a new ward for patients with tuberculosis and other infectious diseases at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, clearing the way for the facility to begin operating next year.

The supervisors’ decision to fund the unit came as a result of a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Zev Yaroslavsky. The money will be enough to staff the unit, set to open in March or April, for just half a year. Going forward, it will cost $2.2 million annually to staff the facility—less than was originally envisioned because of lower operating costs and more potential revenue from moving patients into the facility from other parts of the system. Even the reduced costs, down from $4.6 million originally estimated, will add to the department’s deficit but also will provide needed health care beds for infectious disease patients elsewhere in the overcrowded system.

“It does not make sense for this brand new building to sit empty [when] for a relatively small cost, it could be part of the solution to overcrowding in the hospitals and provide more appropriate care to these long-term patients,” the supervisors’ motion said.

Tuberculosis has been declining for years in Los Angeles County, but public health officials say it is important to remain vigilant. The new ward is seen as an important resource for treating some patients who require long-term hospitalization, including the homeless and those who live with small children and people with compromised immunized systems. The county lost its only dedicated tuberculosis ward when High Desert Hospital in Lancaster closed to inpatients in 2003.

The new Olive View facility also could be used to treat victims of a bioterrorism attack, and, on a more routine basis, for patients with infectious diseases other than tuberculosis. Such patients now often are confined to isolation rooms within intensive care units but could be relocated once the Olive View facility is up and running.

Carol Meyer, chief of operations for the Department of Health Services, said the decision to fund staffing for the new facility was a mixed bag: an added ongoing expense for an already financially-troubled system but, “from a patient perspective, it’s a positive.”

Posted 9/29/10

Meet the new MLK Board

August 10, 2010

If it all begins at the top, the new Martin Luther King Jr. hospital is getting off to a powerhouse start.

If it all begins at the top, the new Martin Luther King Jr. hospital is getting off to a powerhouse start.

A seven-member board of directors for the new facility, being created as a partnership between the county and the University of California, was approved Tuesday by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

The board’s members, who came jointly recommended by the county’s Chief Executive Office and the UC, are Southern California leaders in the fields of medicine, health care management, business and law. (See bios below.)

One of the appointees, Paul King, the president and chief executive officer of Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles Medical Group, said the array of talent and experience on display among his new colleagues would be enough to intimidate many hospital administrators.

However, he said, this will be a board “that understands the difference between governance and management.”

The directors, who are expected to come together soon for their first meeting, will work with the project’s management team as it moves toward opening the facility in 2013. Under the agreement, the county is funding and rebuilding the facility to modern seismic standards while the UC is taking charge of all physician services there. The private, non-profit hospital will have 120 beds.

It will replace the former Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center, which closed to inpatients in 2007 after years of mismanagement and patient care lapses. The idea of joining forces with the UC to create the new hospital was first proposed by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky.

Helping to restore a crucial health care provider to people in South Los Angeles is a strong motivator for the directors, who will serve without pay.

“I think it’s an exciting time,” said one of the new board members, Manuel A. Abascal, a partner at Latham & Watkins. “I think every community deserves great health care.”

Other new directors echoed that sentiment. “I really believe that the South Los Angeles community deserves better access to quality health care,” said Dr. Elaine Batchlor, chief medical officer of L.A. Care Health Plan.

But no one was underestimating the size of the challenge ahead.

“It’s going to be quite the task,” King said. “Most of us who’ve been approached look upon this as a community service, seeking to really return health care to that community…We’ve got a lot to do. 2013 will come faster than anybody thinks.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————

Manuel A. Abascal…

is a Los Angeles attorney who often works on health care cases.

Full bio

Dr. Elaine Batchlor…

is Chief Medical Officer of L.A. Care Health Plan.

Linda Griego…

is president and CEO of Griego Enterprises, Inc.

Paul King…

is president and CEO of Children’s Medical Group.

Michael Madden…

is the former CEO of Providence Healthcare of Southern California.

Dr. Robert Margolis…

is Managing Partner and Chief Executive Office of HealthCare Partners.

James Yoshioka…

is the former president and CEO of Citrus Valley Health Partners.

Full bio

Posted 8/10/10

Crisis looms for L.A. health care

July 27, 2010

The Los Angeles County health care system needs some intensive care—STAT.

The Los Angeles County health care system needs some intensive care—STAT.

That was the message Thursday as officials sounded their most dire warning yet about the state of the deficit-plagued Department of Health Services. The county will have to drop hundreds of thousands of patients and significantly downsize its health care system unless some pending state and federal funding decisions break in its favor—a prospect that is looking less and less likely as Sacramento and Washington hunker down in contentious budget struggles of their own.

“This is a situation that’s increasingly looking like it’s in freefall without a parachute,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, as the Department of Health Services looks to bridge a deficit of up to $429 million this fiscal year.

Of the 730,000 patients now treated each year, some 420,000—more than half—could be turned away, according to a motion by Supervisors Gloria Molina and Yaroslavsky. The cuts would seriously harm some of the sickest people in the county, and also would hamstring the county’s ability to transform itself to meet the demands of federal health care reform, the motion said.

Supervisors approved the motion, directing officials to provide a detailed worst-case analysis in 15 days, after budget updates from the health department and Chief Executive Office provided only a general overview of what will happen if federal and state funding relief does not come through.

The reports did not mention closing hospitals or other health facilities. But the discussion during the meeting made it clear that those actions and others may be on the horizon soon.

“What facilities are going to close? What kinds of facilities are going to close?” Yaroslavsky asked CEO William T Fujioka and Health Services interim director John F. Schunhoff.

The county is looking at three possible ways out of its predicament. There will still be a big deficit to confront, however, even if all three come through.

One hope is to obtain from Congress an extension of the “enhanced FMAP Medicaid matching rate” that would provide some $33.8 million. (FMAP stands for Federal Medical Assistance Percentages.) The measure was not included in the recent vote to extend jobless benefits, however, and it is unclear whether it will be reintroduced in another form.

Another option involves obtaining a favorable decision on the hospital provider fee the county would receive from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS.)That could mean $115 million in fiscal 2010-11.

Finally, county officials have been hoping for an additional $150 million from the so-called “1115 Waiver,” which would provide support to public hospitals that treat needy patients. (1115 refers to a section of the Social Security Act that deals with how Medicaid services are provided in states.)

But those funds could end up being siphoned off by the state of California, which previously had been seen as an ally in negotiating with CMS for the waiver.

“The state’s key interest is helping to solve their budget problem for [fiscal year] 10-11,” Schunhoff told the board.

Molina, the board chair, said it is unrealistic to count on the three options coming through.

“I think we’re being overly optimistic because we haven’t solved last year’s deficit,” she said.

Yaroslavsky noted that the situation is growing worse as the health department continues to spend—with no deficit solution in sight—in the new fiscal year.

“We’re in a very serious situation,” Yaroslavsky said. “We now have 11/12ths of the fiscal year remaining, and we are still spending as if assumptions [of new revenue] are going to come to pass.”

“The longer we wait, the deeper the cuts are going to be,” said Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich.

Supervisor Don Knabe asked the CEO and Health Services chief not to simply propose shutting specific facilities, but to spread the pain throughout the county health system.

And Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas asked that the report include information on county departments, such as the sheriff and probation, that receive unreimbursed health department services.

Underscoring the discussion was the reality that officials here will have to work through the looming crisis, with or without outside help.

“Should the federal and state governments fail to help Los Angeles County obtain essential revenue streams…then this board must be prepared to implement these cuts,” the Molina-Yaroslavsky motion said.

Posted 7/27/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink